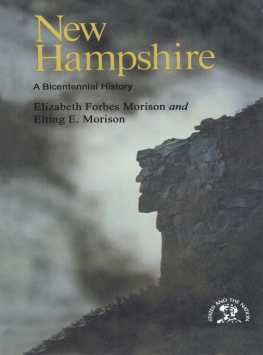

COLONIAL NEW HAMPSHIRE

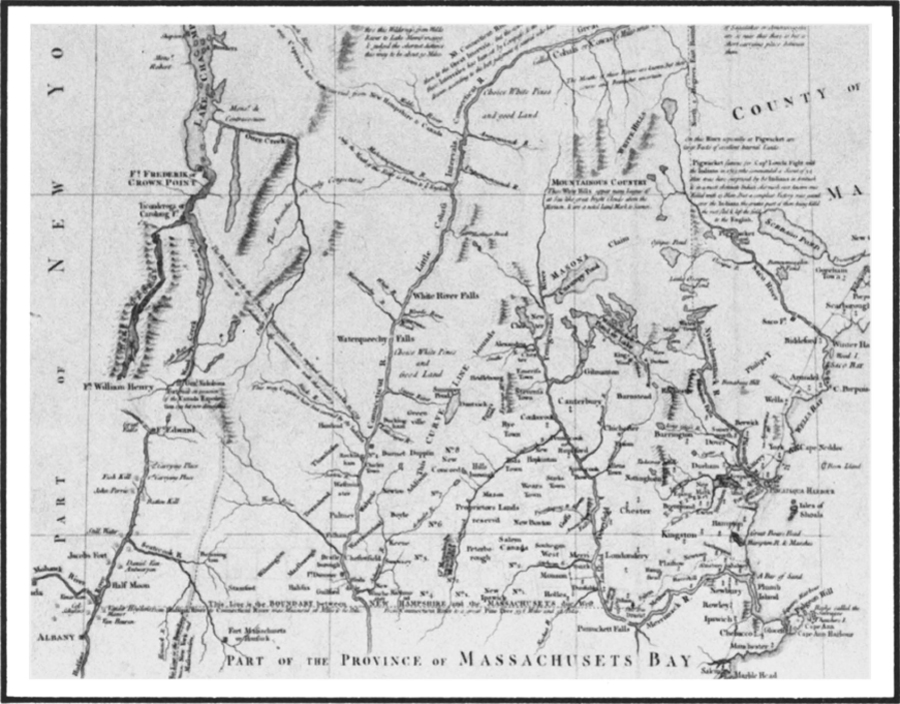

Detail from An Accurate Map of His Majestys Province of New Hampshire in New England published in 1761 by Colonel Joseph Blanchard and the Reverend Samuel Langdon. In 1761 New Hampshire claimed jurisdiction over what is now Vermont. Courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

JERE R. DANIELL

COLONIAL NEW HAMPSHIRE

A HISTORY

University Press of New England

Hanover and London

University Press of New England

www.upne.com

1981 Jere R. Daniell

All rights reserved

First University Press of New England edition 2015

Originally published in 1981 by KTO Press

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-61168-877-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-61168-878-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937169

For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com

TO MY PARENTS

MARY HOLWAY DANIELL

AND

WARREN FISHER DANIELL

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

Friendship, circumstance, and inclination all played important roles in my decision to write a history of colonial New Hampshire. A graduate school friend, Thomas J. Davis, asked me to write the New Hampshire volume for a series on the thirteen original states he helped plan as the historical editor at Charles Scribner and Sons. At the timetwelve years agoI was just finishing a manuscript on late eighteenth century New Hampshire and beginning to think about future writing. Daviss offer intrigued me. My family had roots in New Hampshires past, I had every intention of remaining a resident of the state for some time, my curiosity about the origins of New Hampshire had been whetted by investigation of the revolutionary period, and the existing literature on the colonial period appeared thin. In fact, the three volume History of New Hampshire written by Jeremy Belknap nearly two centuries ago remained the single most frequently cited source of information. Much as I respected Belknap, his work needed redoing.

Since then the state of the literature has improved considerably. In 1970 Charles Clark published The Eastern Frontier, a history of early Maine and New Hampshire especially rich on expansion of settlement in eighteenth century northern New England. My own Experiment in Republicanism, which includes chapters on late colonial politics, came out the same year. David Van Deventers impressive The Emergence of Provincial New Hampshire, 16231741 appeared in 1976. It emphasizes economic development, gives a thorough description and explanation of maritime trade, and includes a wealth of statistical information. Several useful articles on colonial New Hampshire have also been published since I began gathering material for this volume.

summarize developments covered more completely in Experiment in Republicanismmost of the volume is reasonably fresh. The first six chapters cover subjects treated either skimpily or inaccurately in existing literature. I have tried to deal with social and religious change in conceptual terms utilized by modern historians who have written about other New England colonies, but never about New Hampshire. My discussion of local developments emphasizes the abstract as much as the concrete: it should help town historians place their work on individual communities in a broader context. The main purpose of the volume remains unaltered. No comprehensive history of colonial New Hampshire has been written since Belknaps time. Readers may judge for themselves how successfully I have filled the gap.

My debts are many. The bibliographical essay credits past writers whose labors made my task easier. Manuscript librarians in the New Hampshire Historical Society and many other repositories gave me much needed assistance. James Axtell criticized and Charles Clark criticized the entire manuscript; the general editors of the whole seriesJacob Cooke and Milton Kleinmade countless suggestions for improvement, most of which I accepted. Mark Sonnenfeld drew the maps from rough sketches which I prepared. James Garvin, curator of the New Hampshire Historical Society, helped locate and identify illustrative material. Scribners and Dartmouth College helped finance the research. The bulk of my writing was done during sabbatical leaves from Dartmouth. Gail Patten proved an exceptionally accurate, speedy, and efficient typist. I, of course, assume full responsibility for whatever mistakes have remained undetected in the manuscript.

Jere Daniell

Hanover, N.H.

September, 1980

COLONIAL NEW HAMPSHIRE

THE ALGONKIANS

Sometime in the mid-1680s a small group of Pennacooks left their homeland in the upper Merrimack valley to join with fellow Indians to the northeast. They were accustomed to travel and had left their village many times before, but this departure meant more than the others: they had little expectation of returning. Their troubles were almost too vast to comprehend. The oldest among the migrants could remember the days when their sagamore Passaconaway commanded respect from perhaps a dozen bands and tribes in the valley area. Over five hundred strong, they had been able to protect themselves against their traditional enemies to the west, the Mohawks, and to maintain peace with the English strangers who had first arrived during their childhood. Now everything had changed. Disease, warfare, and defection had reduced their numbers to fewer than one hundred. The fish and game on which they depended for much of their sustenance had become scarcer each year, and many fields, where they grew maize and other foods, had been ruined. Indeed, they were threatened with immediate death. Kancamagus, Passaconaways grandson and their present leader, had learned of negotiations between the English and Mohawks which might lead the latter to launch an eastward invasion. If such an attack came, the Pennacooks would be too weak for effective resistance. There seemed no possible course of action but to abandon the land and villages they knew so well.

The Pennacooks were not the only group of Native Americans resident in what is modern New Hampshire when European settlement began, but they were the largest, and their fate symbolized that of the entire pre-colonial population. At the beginning of the seventeenth

The Indians of New Hampshire were members of the complex but linguistically unified Algonkian culture which dominated New England and most of eastern Canada in the centuries before European settlement. The tribe provided the largest unit of communal organization among the Algonkians. These groups ranged in size from perhaps two hundred to a thousand, with the average size about five hundred. They practiced both hunting and agriculture, with the latter more important in the south, the former in the north. The pattern of living within each tribe reflected its economic needs. In most of New England there was a central villagelocated near a body of waterwhich tribal members occupied in the spring and fall for planting and harvesting. Each tribe had its summer fishing grounds, usually on a lake or the ocean where cooling winds offered relief from the ever present insect hordes. Surrounding the village were lands where in the fall and winter smaller family-oriented groups or bands hunted in a manner designed to conserve the available game. Each band worked an area of perhaps twenty square miles and sometimes maintained a small village of its own. The greater the dependence on hunting, the more independent the band was from tribal identification. Tribes themselves sometimes joined in loosely defined patterns of allegiance, most frequently for military purposes.