2018 University of South Carolina

Published by the University of South Carolina Press

Columbia, South Carolina 29208

www.sc.edu/uscpress

27262524232221201918

10987654321

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data can be found at http://catalog.loc.gov/

ISBN 978-1-61117-836-4 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-61117-837-1 (ebook)

Front cover illustration: Detroit Photographic Co.s Oglethorpe Avenue, Savannah Ga. (ca 1900), courtesy of Library of Congress

Preface

M onuments in cities reveal much about the people and their countrys pastTrafalgar Square in London; the larger-than-life statues that honor the Russians who died in defense of Stalingrad; the Lincoln memorial in Washington, D.C. And so it is with Savannah.

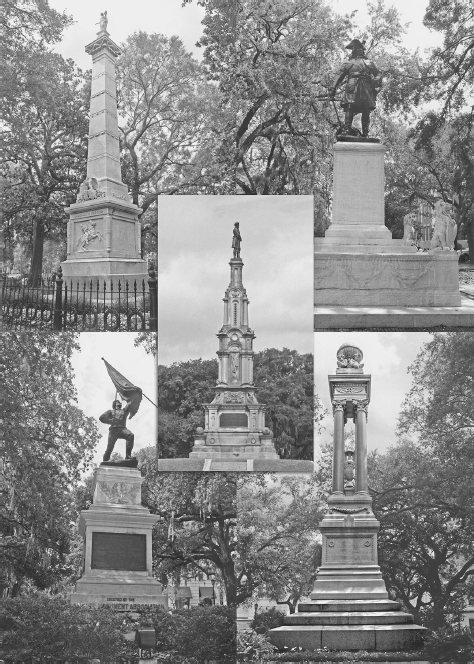

A bronze statue of General James Edward Oglethorpe in the uniform of an eighteenth-century British Army officer crafted by the renowned sculptor Daniel Chester French stands in Chippewa Square. He faces south in the direction of his enemies, ready to defend the city against attack by the Spaniards in Florida and their Native American allies. Atop a tall monument in Madison Square, Sergeant William Jasper rushes forward heroically. He holds aloft a flag he carried during the American assault against the British at the Spring Hill Redoubt in 1779 until a rain of bullets cut him down. During the same assault, a bullet severed the femoral artery of Count Casmir Pulaski, who fell from his horse and died for lack of a tourniquet; a statue in Monterey Square honors his heroism. In Johnson Square stands a monument to General Nathaniel Greene, whose forces swept the British from Georgia and oversaw their evacuation from Savannah. In Wright Square a cenotaph rises in honor of William Washington Gordon, Georgias first graduate of West Point, who founded the Central of Georgia Railway, which revived Savannahs moribund economy in the 1840s. The citys tallest monument stands in Forsyth Park, where a Confederate soldier in battle dress faces north, symbolically defending the city from invasion by another Union Army.

Each monument is that of a white, trained military man who represents order, duty, and preservation of the city; together they give the city a somewhat martial atmosphere. White men like them, a civic-commercial elite, for over 250 years controlled Savannahs government, economy, politics, urban development, and its predominant culture even though the citys population was sometimes nearly evenly divided between black and white.

Dramatic change in the citys political leadership came only in the mid-1990s when the African American population had grown to 57 percent. Savannah elected two black men as mayor, Floyd Adams and then Dr. Otis Johnson. Each served two four-year terms, the maximum allowed. They were followed by Edna Jackson, the first African American female to serve as mayor; she took office in 2012. The City Council members elected with them were about evenly balanced between black and white.

Monuments to these men, like those who came after them, represent a white, civic-commercial elite who dominated Savannahs politics, culture, and economy for 250 years. Center, Confederate War Memorial. Top left, monument to Count Casimir Pulaski, killed in the Siege of Savannah in the Revolutionary War. Top right, monument to General James Oglethorpe, founder of Savannah and Georgia, 1733. Bottom left, monument to Georgia Revolutionary War hero Sergeant William Jasper, killed in the Siege of Savannah. Bottom right, cenotaph in honor of W. W. Gordon, founder of the Central of Georgia Railroad. Photographs courtesy of Bob Paddison.

The African American Family Monument, located on the John P. Rousakis Riverfront Plaza. The last line of the inscribed tribute, written by poet Maya Angelou, reads, Today, we are standing up together with faith and even some joy. Photograph courtesy of Bob Paddison.

With such profound change in the citys governmental leadership came new and very different monuments. Dr. Abigail Jordan, a University of Georgia graduate, initiated a petition drive in 1991 to erect a memorial to the citys African American community, some of whom were her forebearers. After eleven years of often acrimonious debate over the location, images, and inscription, a monument went up on River Street, where nearby shackled Africans once were herded ashore from slave ships.

A seven-foot bronze statue by local sculptor Dorothy Spradley depicts a standing father, mother, and two children dressed in twenty-first-century clothes, their broken chains at their feet. The original inscription on the base of the statue, written by Maya Angelou, read: We were stolen, sold and bought together from the African continent. We got on the slave ships together. We lay back to belly in the holds of the slave ships in each others excrement and urine together, sometimes died together, and our lifeless bodies thrown overboard together. But the City Council objected to the wording, which they feared might offend some of the vast numbers of tourists who strolled nearby. Ms. Angelou proposed an additional line: Today, we are standing up together, with faith and even some joy.

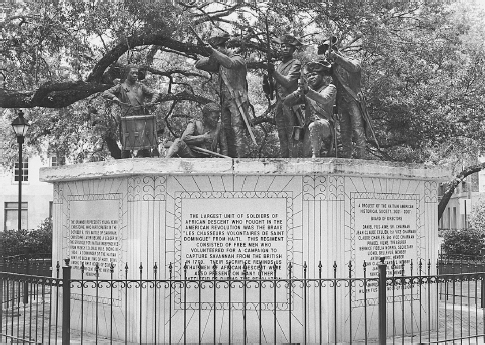

Part of the inscription on the Haitian Monument in Franklin Square reads, Their sacrifice reminds us that men of African descent were also present on many other battlefields during the Revolution. Photograph courtesy of Bob Paddison.

in the

in the