Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

About NYU Press

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

September 12

September 12

Community and Neighborhood Recovery at Ground Zero

Gregory Smithsimon

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York and London

www.nyupress.org

2011 by New York University

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smithsimon, Gregory.

September 12 : community and neighborhood recovery at ground zero /

Gregory Smithsimon.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8147-4084-2 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-8147-4085-9 (pb) ISBN 978-0-8147-8671-0 (e-book)

1. September 11 Terrorist Attacks, 2001Economic aspectsNew York (State)New York. 2. Battery Park City (New York, N.Y.) 3. BuildingsRepair and reconstructionNew York (State)New York. 4. Manhattan (New York, N.Y.)Economic conditions. I. Title.

HV6432.7.S65 2011

974.71044dc23 2011020454

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

For a project about taking space seriously, it makes sense to organize my acknowledgments spatially. Starting in Battery Park City, I want to thank the residents, local activists, and leaders whose welcome into their neighborhood made my research there possible. Alison and Robert Simko at the Battery Park City Broadsheet have been a considerable resource to me and to the community. Across Chambers Street from Battery Park City is the Municipal Archives. Its a pleasure to go there in no small part because of its director, Kenneth Cobb, who pleasantly initiates researchers into the wonders of the archive even though in that job theres no end to either wonders or researchers.

Riding the train north to Columbia Universitys campus, I owe thanks to many people: Sudhir Venkatesh, Herbert Gans, Charles Tilly, all of whom made this project better by persisting in asking me questions I didnt always want to answer. I was aided in my research on New Settlement Apartments by Alex Demshock while she was a student at Barnard College. Her connections with the area were of great use in gaining entre to New Settlement staff. Lance Freeman, Susan Fainstein, and Lynne Sagalyn took time to consider my questions about Battery Park City and public spaces and gave me valuable direction in my research. I owe particular thanks to Priscilla Ferguson for lending me her office during the summer I was revising my manuscript. It was a perfect retreat where my most productive days were spent.

Those days would not have been quiet and productive had my mother-in-law Susan Simon not been nearby to watch my daughter. Susan also proofread an early draft of the entire manuscript, when it was a Herculean undertaking. I am deeply appreciative.

Brooklyn Colleges congeniality has been unsurpassable. The Department of Sociology has some of the most supportive and helpful colleagues anyone could ask for. Sharon Zukin has provided inspiration and insight all along the way. Tamara Mose Brown read drafts of every chapter. Alex Vitales work provided a valuable foundation for my framing of the post-1975 crisis history of New York. Along with Brooklyn College, the Graduate Center at the City University of New York is home to an unmatched collection of urbanists, whose collegiality has always set them apart as much as their cutting-edge scholarship.

Further afield, geographically at least, my thanks to Louise Jezierski, who got me started down the path with an introductory urban studies course during my first semester as an undergraduate. She introduced the class to Jane Jacobss Death and Life of Great American Cities, despite, I later found out, her misgivings about Jacobss book for its lack of a good old-fashioned analysis of power. The book was what hooked me on urban studies, though I immediately shared Jezierskis sense that its story was incomplete. Part of the purpose of this project is to fill in the missing explanations about the role of power in shaping urban space.

Down in Maryland, I thank my parents, who have encouraged me without reservation in everything I did, despite the reservations they could reasonably have had. What I owe them goes far beyond this project, of course, but within the project, raising me in the suburbsand taking us to Baltimore ethnic festivals, Washington, D.C., museums and even one memorable New York City Thanksgiving Day paradeno doubt primed my fascination with cities and public spaces.

At the end of this tour, I return home to Brooklyn to thank my family. My daughter Una was my first research assistant, accompanying me to the playgrounds of Battery Park City until they became part of her neighborhood. My son Eamon grew up looking forward to trips there as well. My wife Molly has been the enigma at the center of my urban research: a Manhattanite by birth with no particular affection for the city; someone who falls asleep reading most urban sociology but because of that is best able to tell me what parts of my project are most interesting; the person who was serious about making sure I had the time I needed to complete this project but just as serious about insisting that that time not go on forever. As with every other ambitious thing Ive tried, I simply couldnt have done it without her.

September 12

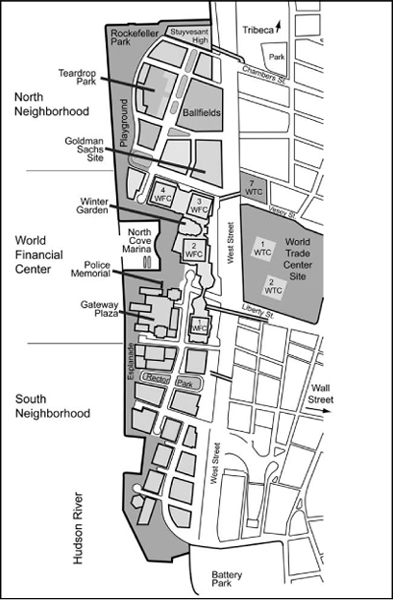

Map of Battery Park City

Introduction

LOWER MANHATTAN BROILED while Battery Park City was balmy. The contrast was evident in the tempo and temperature of the streets, sidewalks, and parks of the two adjacent neighborhoods. I pushed my daughters stroller along the crowded sidewalks, making my way from Lower Manhattan to Battery Park City. It was a hot May day eight months after the Trade Center attacks of 2001. The narrow streets of downtown New York City clattered with the areas daily rhythms. Delivery trucks clogged Chambers Street, filling the air with dry exhaust. Heat reflected off the asphalt rutted by the constant passage of buses and taxis. Battery Park City was very different on days like this; a strong breeze blew off the Hudson River across the park and promenade and continued along largely traffic-free streets.

Though the two neighborhoods were intimately connected, their physical and social organization differed. Lower Manhattan, like much of the city, had long presented inequality at closer quarters, adjoining rich and poor, powerful and powerless. In the street-level mall of a bank office tower on Wall Street, bank employees hurried toward a subway entrance while heavily dressed homeless men took an air-conditioned respite at caf tables. On the southern tip of Manhattan, American and foreign tourists picked their way through immigrant vendors selling New York City T-shirts, art, and souvenirs to wait under the sun for a ferry to the Statue of Liberty or Ellis Island. The heart of the Financial District, in front of the New York Stock Exchange, was preternaturally quiet behind roadblocks, security, and newly arranged concrete and steel barriers. Occasionally a trader in a color-coded suit jacket emerged from the Exchange for a cigarette. On Nassau Street, the most racially diverse street in the Financial District, workers from the surrounding financial firms, Pace University, and government buildings walked down the narrow pedestrian street, past mobile phone and jewelry stores to the lunch shops on the corners. Well below ground level at the vast World Trade Center site, construction equipment roared and beeped as it continued the slow process of clearing rubble from the site in anticipation of an ambitious redevelopment program. Each image was a reminder that typical New York streets not only included a wide diversity of occupations, nationalities, races, and classes but also displayed substantial inequality in resources and privilege from block to block.