First published 1970 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2006 by Taylor & Francis. Copyright 1970 by Frederick O. Gearing.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2006040713

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gearing, Frederick O., 1922-

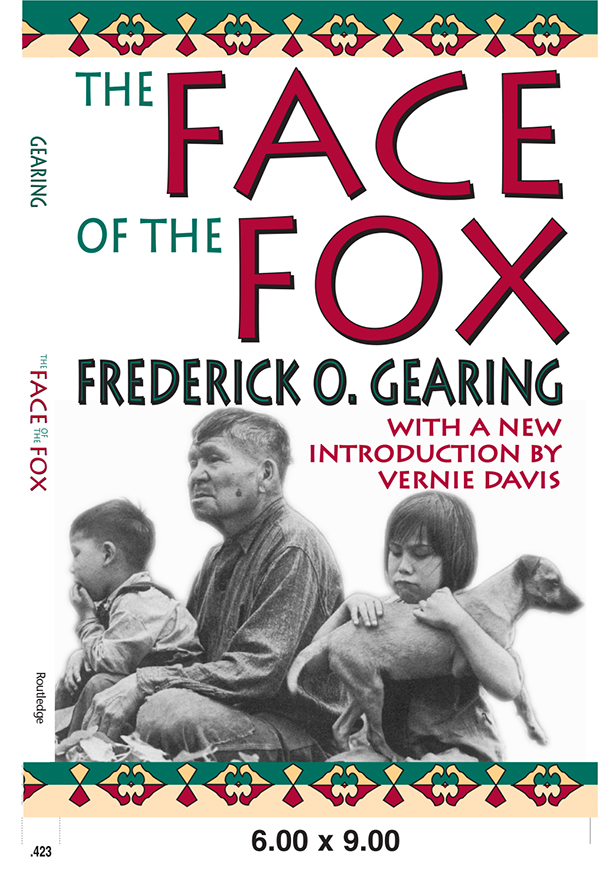

The face of the fox / Frederick O. Gearing : with a new introduction by Vernie Davis.

p. cm.

Originally published: Chicago : Aldine Pub. Co., 1970.

With new introd.

ISBN 0-202-30842-1 (alk. paper)

1. Fox Indians. I. Title.

E99.F7G4 2006

305.897'3140775614dc22

2006040713

ISBN 13: 978-0-202-30842-5 (pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this book but points out that some imperfections from the original may be apparent.

Frederick Gearings insights from The Face of the Fox are as relevant today as when he did his fieldwork almost a half century ago. This classic book illuminates principles that apply to estrangement and conflict across cultures of any time and place, and it deserves to be read by anyone interested in multicultural studies, peace and conflict studies, or global studies, as well as sociology and anthropology. One of the tests of truly outstanding anthropological work is that it transcends the particular location and time period of the study to inform us about some universal human trait that is as relevant to our lives as to those in the study. This book is a rare gem that is not only as pertinent today as when it was written, but will remain relevant in understanding future intercultural conflicts.

Most anthropological studies focus on a particular culture as though it exists in isolation, unattached or unconnected to others. Gearing examines the intersection of two cultures that live their lives in ways that bring them together in some ways, primarily economically, and, yet, who live in very different worlds shaped by significantly different worldviews. This is a microcosm of the world in which we all live today. Those of us living in the U.S. are currently in conflict with millions of people in the world with whom we do not even know we have a relationship.

Gearing makes two unique contributions in this book: the first is that he examines the process by which two cultural groups, living side by side and even interacting in some aspects of their lives, manage to see the world in two profoundly different ways and how this leads to alienation and conflict between the groups; the second is that he explores the question of how one might go about intervening constructively to decrease this estrangement.

Anthropologist Frederick Gearing (1970) ran headlong into the conflict caused by differences in cultural reality when he went to central Iowa in 1952 as part of an Action Anthropology project to learn about the Mesquakie Indians (called Fox Indians by their white neighbors). What he discovered were two communities, white and Indian, living near each other, often interacting through work and commerce, but living in two very different mental worlds. Estrangement, Gearing points out, is not just contempt or indifference. Even altruistically motivated outsiders such as Peace Corps or VISTA volunteers have trouble getting outside their own headstheir own cognitive frameworksto relate to others by seeing the world through their eyes. Gearing set out to understand the words connected to the different worldviews of the whites and the Indians.

The Mesquakie community lived on 3,350 acres about two miles from the small town of Tama, Iowa. The Mesquakie shopped and worked (often in construction and factory jobs) in Tama and other surrounding towns. As Gearing went to Tama to buy groceries and newspapers, he met and talked to white Iowans who freely shared their view of the Mesquakie from living and working together over the years. One of the most compelling themes that emerged from the white view of the Mesquakie was that the Indians are unambitious and undependable (pp. 16-18). The Mesquakie, on the other hand, viewed themselves in very different terms, as generous and harmonious. These different perspectives of the same observable reality were shaped by different cultural lenses. Take for example the observable differences as one drives along the road. It was easy according to Gearing to distinguish between the Mesquakie farms and the neighboring white Iowan farms devoted to the same crops.

Here and there, set back in small, green clearings some distance from the road, were the homes: small frame houses, generally unpainted or not recently painted; often there was a second structure a few yards away, one of the bark-covered, loaf-shaped traditional homes of these Indians, called by them wikiups. (p. 8)

These contrasted sharply from the way the white Iowans tended and controlled the landscape on their farms and home-steads.

The white Iowan farms had a geometric precision about them while the Mesquakie fencerows were more uneven and the fields somewhat rounded. The Mesquakie, Gearing says, did not appear particularly intent on holding the land in check (p. 41).

In contrast, the

White Iowans grew lush, ten-foot-high com in hundred-acre plots, bought spindly calves and fed them the com and sold them later as prime beef.... These white men practiced a highly mechanized, tightfisted, hardheaded, intense, tightly scheduled, and (given government subsidy) a very profitable way of farming. White men in Iowa thus took wealth from nature, turned much of the wealth into machines, and turned the machines back against nature to extract more wealth. (P- 17)

From the white Iowan perspective it was easy to see that the Mesquakie were not like themselves: they were not ambitious and did not successfully exploit the land. The Mesquakie would not have framed their perspective around whether they successfully exploited the land. Rather, Gearing says, they would have described ... an order that bound together nature and the [Mequakie] in reciprocal necessity, one to another (p. 42). Gearing provides us with two cultural perspectives on the same observable facts: from the white Iowan perspective the Mesquakie are unambitious; the Mesquakie, on the other hand, see themselves in harmony with nature.

In another illustration of the illusion of cultural perspective, the white men who worked side by side in factories and con-struction crews saw that the Mesquakie worked hard. But they also viewed them as undependable. For example, a Mesquakie ...was getting into his car to leave his house for work when his uncle walked up, and they talked about the weather; the uncle mentioned casually that he thought he might go to Marshalltown if he could get a ride; nephew and uncle got in the car and went not to work, but to Marshalltown (p. 17). The white boss and co-workers see another example of Mesquakie being undependable. The uncle or another Mesquakie, on the other hand, see an example of his being generous. I might add that the uncles casual mention that he might go to town if he could get a ride would not even look like a request for a ride by a white Iowan. Among some other cultures, however, requests are never stated directly lest they obligate the other rather than allowing him or her to offer freely (cf. Lee, Avruch, Augsburger).