Series

Historos

supervised by Luciano Canfora

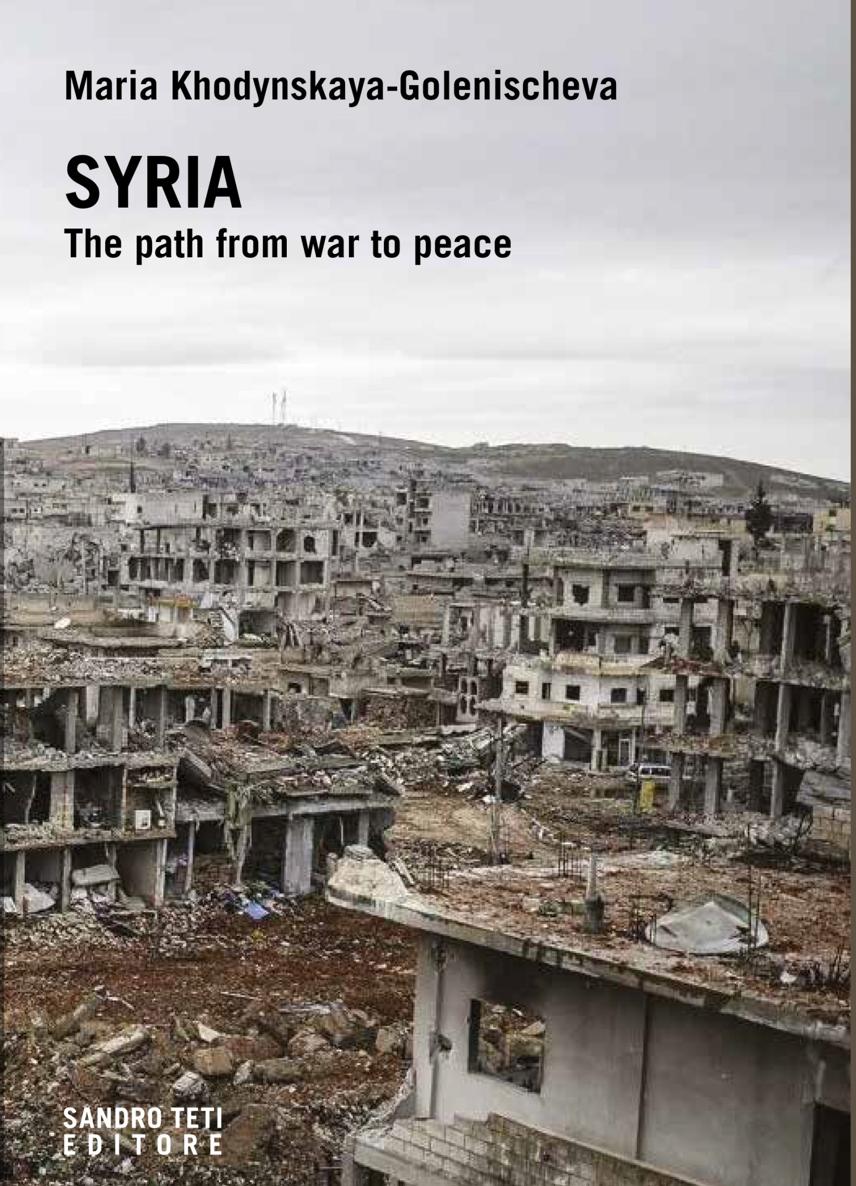

Maria Khodynskaya-Golenischeva

SYRIA

The path from war to peace

Ebook version created by

Claudia Pasquali

Graphic design

Laura Peretti

Teti S S.r.l.

Viale Manzoni, 39 00185 Roma

T. +39.06.58334070 M. +39.389.7847802

www.sandrotetieditore.it info@sandrotetieditore.it

ISBN: 9788831492300

Copyright 2021 Sandro Teti Editore

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.

INTRODUCTION

The Syrian Crisis is the hallmark conflict of our day. Having begun in 2011 with national protests calling for political freedoms and improvement in the socio-economic state of the Syrian people, the Syrian conflict has since evolved into an arena of bitter confrontation between various global and regional players, including Russia, the United States, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the EU and others, and has become a testing ground for experimenting with innovative formats of cooperation between the forces involved in the conflict.

This sometimes-adversarial and sometimes-cooperative layer became an added weight on the already-stretched canvas of the intra-Syrian military-political confrontation. In parallel with the evolving conflict, an intra-Syrian component emerged from this crisis space brought on by the growing and increasingly complicated entanglement of confusing contradictions between global and regional players and their desire to promote their agendas by avoiding already-established mechanisms and processes.

The Syrian crisis cannot be examined in isolation from the current general political and geostrategic state of the world. The current watermark of the world order, which has been significantly impacted how the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic (SAR) has evolved, indicates substantial growth of the potential of the countries in the region and their increased determination to pursue their interests more aggressively and expand their sphere of influence. This is in full view in the Syrian conflict, where countries of the region (Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran) initially sought to monopolize the crisis management by providing financial, logistical and material assistance to anti-government groups (evidence suggests that Saudi Arabia supports Jaysh al-Islam, Qatar Faylaq al-Rahman, Turkey Ahrar al-Sham, Jaysh Tahrir as-Suria etc.). It is also worth mentioning Iran and the assistance it provided not only to the SAR authorities but also to those pro-government groups that assisted Damascus in its fight against armed opposition groups and directly participated in the conflict. The protracted nature of the crisis contributed to the consistently growing involvement of external forces, which did not want to lose the material, political, and, in some cases, human resources they had invested in achieving their various military-political goals.

Hence, the Syrian conflict is truly worthy of closer analysis, placing it in the context of how a system of international relations can be transformed (in exactly the same way they were included in the logic of the bipolar confrontation under the Yalta-Potsdam world order) and the overall impact on the regions system for providing security.

If we view this from a global perspective, then we can say that at the beginning of the Syrian crisis (for the purpose of this review, in 2011-2014) relations between members of world community and Syria could be characterized by some as pronounced dualism: the conflict divided its members into supporters and opponents of the Assad regime . In both camps there was an assumed leader supported by a group of countries (Russia lead China, Iran, Iraq, Algeria etc., while on the other side the USA lead Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, and the European Union). However, this conditional, almost artificially resurrected bipolarity, would later show signs of relapse as its footing was never on solid ground and therefore could not last long. The reason for this were the multi-directional approaches applied by the different states, each weighed down by its numerous internal nuances. Now and then contradictions between elements of the two blocs would emerge, as would a lack of linearity in the gradation of allies interests in the Syrian dossier. This can be seen clearly in the contradictions that existed between the US and Turkey (NATO allies) regarding Washingtons use of the Kurdish militia for their counterterrorist tasks in Syria. If we look outside the Syrian context, we see yet another crisis in 2017 between Qatar on the one hand and the Arab Quartet on the other, which had a direct impact on the situation on the ground in Syria and aggravated the contradictions that existed between anti-government factions sponsored by the above-mentioned Arab States. And, the disagreements between the US and some EU countries about the fate of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action for Irans nuclear program, a situation which could not help but affect the situation in and around Syria. And finally, Russia-Turkey cooperation, over the course of which many groundbreaking results were reached (both in terms of the situation on-the-ground and the political process), but which was never without its difficulties and which experienced both highs and lows, including very tense moments in bilateral relations. The list can go on and on.

This looseness, or the lack of a coherent system of priorities, which could serve to bind the members of two camps, fueled intra-regional antagonism and disagreements between global and regional players and led to the gradual disintegration of the two blocs and the spontaneous formation of radically innovative formats and instruments to solve the Syrian crisis.

Without a doubt traditional mechanisms that were created in the post-war period played their part in the conflicts resolution the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly and others. However, as the conflict evolved, so did the limitations of the UN Security Council. First of all, there was a lack of political will on the part of those states of the region that possessed direct influence on the Syrian crisis to implement Security Council resolutions, which in turn made the implementation of said resolutions, even with consensus of the five permanent members, an impossible task.

By 2015, the Syrian conflicts center of gravity gradually began shifting and the search began for mechanisms that better corresponded to the realities of that period. The years 2015-2018 marked the advent of such new formats as the Syrian Action Group, the International Syria Support Group, the Lausanne meeting and the Astana and Amman platforms.

Under these changing arrangements new trends soon emerged: if previously discussions about the Syrian peace process predominantly involved Russia and the United States, and were further reinforced with the involvement of concerned states (including countries in region), then the Astana process (International meetings held on the topic of Syria in Astana), marked an upsurge in fundamentally new trends. First of all, in order to make perceptible progress (examples being the agreements reached between Russia, Turkey and Iran about the 2016 ceasefire, the decision taken in the context of the Astana and the Amman processes for the creation of de-escalation zones in 2017, the formation of the Constitutional Committee in 2019) participation of the two global powers, Russia and the United States, was no longer required. More significant, however, was how influential states in the region began to accept their respective obligations. Second, the resolution of the Syrian crisis (in addition to other present-day conflicts) could now involve deeply cooperative, albeit thematic, interaction between players who support various opposing forces. That they stood on opposite sides of the barricades did not at all exclude their mutually beneficial cooperation on issues of common interests. And as it turned out, several countries in the region were capable of such cooperation (primarily, Turkey and Iran), as well as Russia, whose policies were characterized by its abandonment of the bloc mentality and willingness to interact with all parties without exception, both political and armed forces involved in the crisis (with the exception of terrorist organizations, of course), as well as their external sponsors. The United States was not afforded such a luxury because, in part, of its anti-Iran stance and its uncompromising strategy to topple Bashar Assad, which prevented the US from having any contact with Damascus.