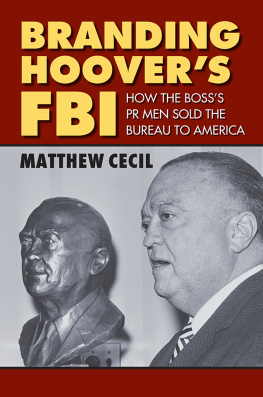

Branding Hoovers FBI

Branding Hoovers FBI

How the Bosss PR Men Sold

the Bureau to America

Matthew Cecil

University Press of Kansas

2016 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cecil, Matthew, author.

Title: Branding Hoover's FBI : how the boss's PR men sold the bureau to America / Matthew Cecil.

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, 2016.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016023587

ISBN 9780700623051 (hardback)

ISBN 9780700623068 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hoover, J. Edgar (John Edgar), 18951972. | United States. Federal Bureau of InvestigationHistory. | Criminal investigationUnited StatesHistory. | Public relationsUnited StatesHistory. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Freedom & Security / Law Enforcement. | BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Public Relations.

Classification: LCC HV8144.F43 C423 2016 | DDC 363.250973/0904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016023587.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

PREFACE

Although the process of writing history is a solitary task, I had a great deal of help and support in gathering the information for this volume. First, the FBIs Records Management Division and its Record/Information Dissemination Section were, as always, unfailingly helpful. Considering the volume of requests that the Bureaus Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) staff deals with, it is remarkable that files are processed and released as quickly as they are. None of my research would be possible without their help, and I am grateful. Special thanks go to Rebecca Bronson from the FBIs Records Management Division, who helped me focus and limit my requests in order to speed up the process.

Many others in far-flung locations helped to create this book. Thanks to Joe P. Harris, who operates a National Archives research business in Maryland. Harris obtained most of the photographs in this book from the National Archives Records Administration (NARA) Still Picture Branch in College Park. The staff in the document section of the NARA assisted me during my visit there to review the Louis B. Nichols FBI file and other related documents. Retired journalist Walter Rugaber consented to an interview that added much to my understanding of FBI official Deke DeLoach. Muriel Jones Cashdollar provided insight into her father, Milton A. Jones, and contributed a photograph of her family with J. Edgar Hoover. Sally Stukenbroeker Pellegrom likewise spoke to me about her father, Fern C. Stukenbroeker.

I am grateful also for the work of authors and historians Douglas M. Charles of Pennsylvania State University and Athan Theoharis of Marquette University, who reviewed the proposal for this book and offered useful feedback and suggestions. Denver-based wordsmith Carrie Jordan edited the first draft of this manuscript, demonstrating great skill and patience and dramatically improving the end product. I appreciate the forbearance of my Wichita State University (WSU) colleague Jeffrey Jarman, who allowed me to interrupt him frequently to talk through the analysis in these pages. WSU colleagues Jessica Freeman, Kevin Keplar, Bill Molash, Sandy Sipes, and Amy Solano provided endless good humor that lightened my writing hours in the office. My wonderful wife, Jennifer Tiernan, is always supportive and also helped me test and focus the theories and analysis for this and many other research projects. Numerous other WSU colleagues supplied support and good humor as well. Thanks to Ron Matson, dean of the Fairmount College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at WSU, who provided research support and personal encouragement. Thank you to Editor-in-Chief Michael Briggs, Director Charles T. Myers, and the staff at the University Press of Kansas for showing confidence in this project; they are talented and patient, and I am thrilled with the result of their work that you are holding in your hands right now.

I want to thank my parents, Charles and Mary Cecil, who have always given rock-solid support to me and my siblings. Thanks to my son, Owen, for inspiring me with his goofy sense of humor and his remarkable writing talent. Finally, I must offer a special thank you to J. Edgar Hoover for creating the meticulous record-keeping system at the FBI that makes possible the detailed study of the agency he built.

Introduction:

Defining a Hoover Era

Historians and politicians like to brand time periods with evocative labels. Eras are declared. Historical epochs are christened. Sometimes, the principal characters of an age attempt to declare an era themselves, with varying levels of success. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) offered a New Deal, and it stuck. President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) argued for a Great Society. President Harry S. Truman did not have quite the same success declaring the era of a Square Deal, and few remember the Gerald Ford administration as the WIN years (Whip Inflation Now). At times, eras are named by historians. Senator Joseph McCarthys four-year tirade of alcohol-fueled fearmongering and self-promotion turned his name into a pejorative, McCarthyism. Events themselves may define an era. The first world war, the Great War in its time, became World War I after a second global conflict arose and was slotted in as World War II. Sometimes, the media name an era, and the name sticks. President Ronald Reagans eight years of trickle-down policiesReaganomics or voodoo economics, depending on your politicshave become accepted as defining a Reagan era. President Bill Clintons tenure in the Oval Office gave us what is becoming known as the Clinton years. It seems possible that the Obama era will be defined in the future by his signature legislative accomplishment, the Affordable Care Act, but under a title conferred derisively by some but adopted by Barack Obama himselfObamacare.

One might imagine, then, that a towering figure like FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, a man who loomed over American society as a singular individual of power and authority for decades, might warrant an era of his own. No influential figure in American history held power longer than the FBI director who served for nearly fifty years, from his late twenties into his late seventies. When Hoover became director, many Americans had yet to have their homes connected to an electrical grid. By the time he died, Americans had tired of routine voyages to the moon. Hoovers reign overlays most of the named eras of the so-called American century, from the Roaring Twenties to the Great Depression, World War II, and McCarthyism and into the Cold War. Eight presidents, from Calvin Coolidge to Richard Nixon, oversaw Hoovers work, at least in theory. Seventeen attorneys general served as his immediate supervisor, at least nominally. None of those attorneys general, save perhaps Robert F. Kennedy (RFK), remotely approached the FBI directors notoriety, and none achieved anywhere near the kind of power he accrued and wielded. Hoover led a seemingly omnipotent agency, capable of tracking outlaws, unmasking spies and communists, and performing miracles of science in its laboratory. Historians generally agree that Hoovers specter loomed over elected and appointed politicians throughout nearly all of his forty-eight years in office as one of the most powerful figures in American society. For decades, the bulldog visage of the FBI director instilled fear in the hearts of criminals, dissidents, and public officials alike. Historians have not generally acknowledged the middle fifty years of the twentieth century as a J. Edgar Hoover era, yet Hoovers astonishing power and influence over events is frequently acknowledged in studies of other prominent American characters and eras. Though Hoover was viewed by a majority of Americans as a strong and generally effective figure during his lifetime, understandings of the actual extent of his authority over his nominal superiors and of his narrow-minded character have only grown in the decades since he died.