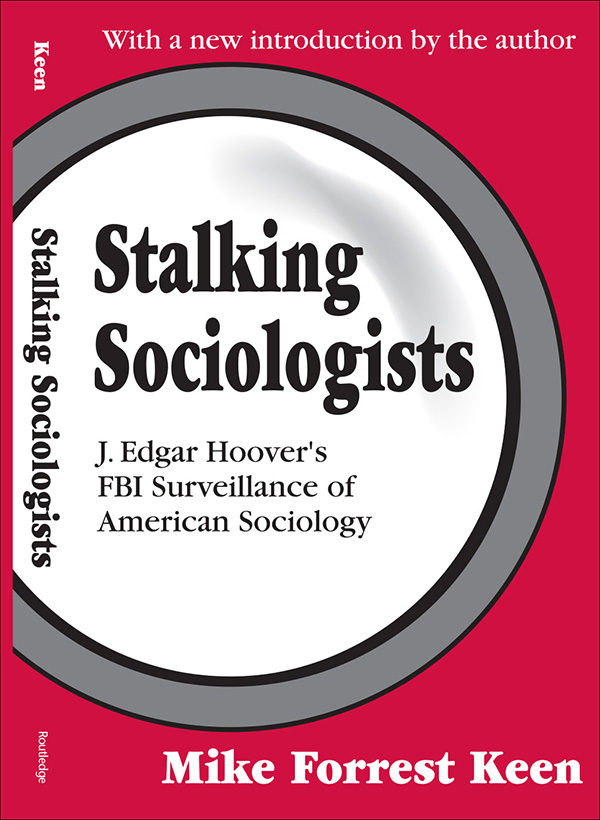

Published 2004 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon 0X14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2004 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2003065011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keen, Mike Forrest.

Stalking sociologists : J. Edgar Hoovers FBI surveillance of American sociology / Mike Forrest Keen.

p. cm.

Rev. ed. of: Stalking the sociological imagination. 1999.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7658-0563-4 (alk. paper)

1. SociologyUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. United States. Federal Bureau of Investigation. I. Keen, Mike Forrest. Stalking the sociological imagination. II. Title.

HM477.U6K44 2003

301.0730904dc22

2003065011

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0563-8 (pbk)

Introduction to the Transaction Edition

It seems like deja-vu, all over again.

Yogi Berra

Preserving our freedom is one of the main reasons that we are now engaged in this new war on terrorism. We will lose that war without firing a shot if we sacrifice the liberties of the American people.

Senator Russell Feingold, lone vote against USA PATRIOT Act

The movement from one project to the other, from a schema of exceptional discipline to one of a generalized surveillance, rests on a historical transformation: the gradual extension of the mechanisms of discipline throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, their spread throughout the whole social body, the formation of what might be called in general the disciplinary society.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish

As I write this new introduction for the Transaction edition, it is tempting to join in the widespread chorus, Since 9/11, everything has changed. Certainly we have a newly heightened sense of vulnerability in the wake of the most devastating attack to have occurred on our soil since Pearl Harbor. We think twice about a trip to Washington, D.C., and worry about living in New York City. As millions of us watched the streaming video of the space shuttle Columbia break apart in the clear blue sky over Texas, almost immediately a thought that wouldnt have occurred to us prior to 9/11, crossed the American mindscape, Was this another terrorist attack? As we move from a yellow to an orange alert, and back again, the homeland security warning system is teaching us the color of terrorism. The most recent mantra from our homeland security officials seems hauntingly familiar: duct and cover. In the face of this national insecurity, polls show many Americans increasingly willing to sacrifice civil rights and constitutional protections of privacy for promises of safety and security.

Recognizing opportunity amidst these fears, the secrecy and surveillance hawks within and circling around the current administration are attempting to capitalize on our fears in order to dismantle the few reforms and protections that were placed on our intelligence agencies in the aftermath of Watergate and revelations of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBIs secret, widespread, and often illegal surveillance of hundreds of thousands of Americans. In the name of national security, a new cloak of secrecy is being laid over the inner workings of our most powerful and pervasive government agencies even as new laws, executive directives, and technological advances provide them with unprecedented capabilities for domestic intelligence and nationwide surveillance.

When I originally wrote this book, fears of nationwide surveillance, domestic intelligence and FBI abuse appeared to be more the historic grist and analytic concern for a burgeoning body of FBI and FOIA scholarship, than the very real and pressing, if not threatening, issues they have once again become today. But has everything changed? FBI domestic intelligence and surveillance have been an integral component of the Bureaus activities since its very inception. So too, have been fears about abuse of its powers and potential to serve as a national secret police force.

Nonetheless, beginning with the white slavery scare between 1910 and 1914, and continuing during World War I and through the Red Scare that followed it from 19191921, the Bureau was engaged in a number of controversial domestic intelligence activities. These included the infamous Palmer Raids, as well as the monitoring of a wide spectrum of radical and liberal activists and organizations.

Between 1917 and 1921, the Bureau compiled more than 200,000 dossiers on American organizations and residents.

However, all the resulting criticism and controversy notwithstanding, the Red Scare made the Bureau, insuring its early power and prestige.

In accepting his initial appointment to the helm of the Bureau, a wily and politically savvy Hoover appeared to support Attorney General Stones strictures, writing I could conceive of nothing more despicable nor demoralizing than to have public funds of this country used for the purpose of shadowing people who are engaged in legitimate practices in accordance with the constitution of this country and in accordance with the laws of this country.

Capitalizing on the expanded authority it had obtained from the Roosevelt administration, in the 1940s and 1950s, during World War II and the Cold War that followed, the FBI once again used fears of threats to national security and anti-Communist sentiments to continue to increase its resources and to further develop its domestic intelligence capabilities. From 1936 to 1952, FBI appropriations expanded 1800 percent, and the number of its personnel increased from 609 agents and 971 support staff, to 6,451 agents and 8,206 support staff.