Published by University of Otago Press

PO Box 56 / 56 Union St West, Dunedin, New Zealand

Fax: 03 479 8385 / Email:

First published 2002

Copyright Jim McAloon 2002

ISBN 1-877276-23-5 (print)

978-0-947522-03-2 (Kindle)

978-0-947522-04-9 (ePub)

978-0-947522-05-6 (ePDF)

Published with the assistance of The History Group,

Ministry of Culture and Heritage

Ebook conversion 2016 by meBooks

CONTENTS

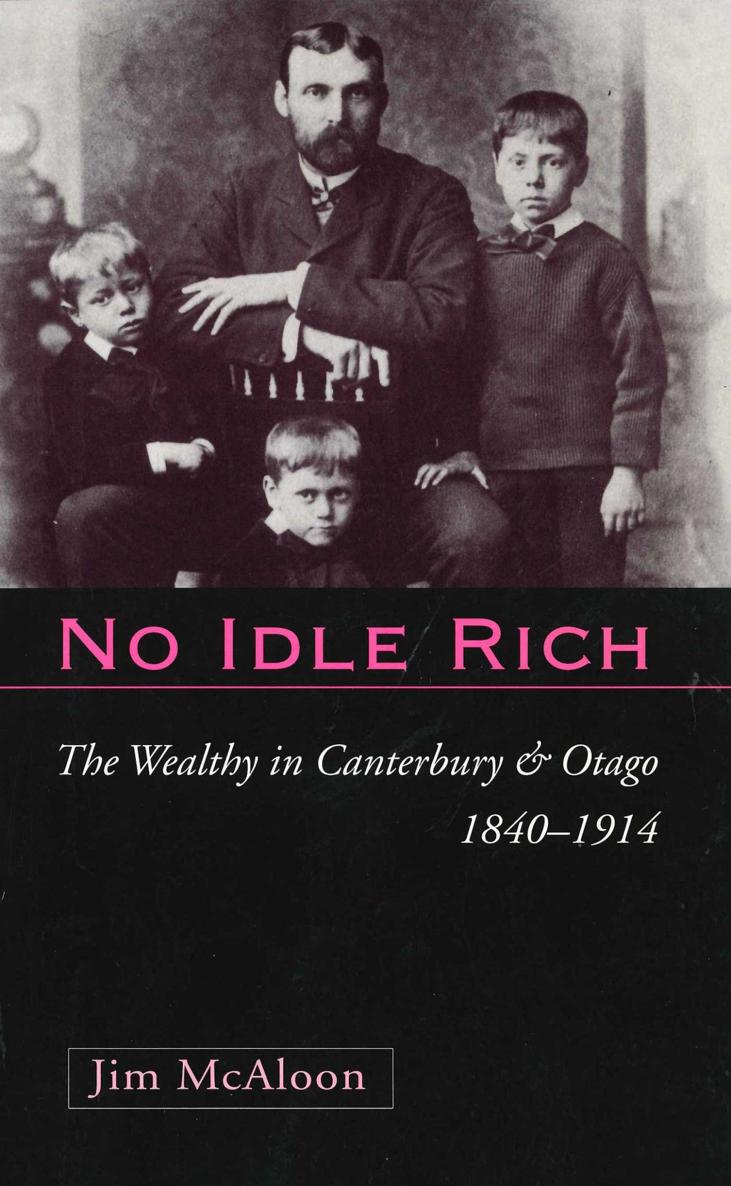

A section of photographs appears between pages 112 and 113 .

J. M. Ritchie and three of his sons (plus dog). The solemn little fellow at his fathers left is George Ritchie, who followed his father as General Manager of the National Mortgage and Agency Co. (Hocken Library c/neg E565/3)

PREFACE

I have lived with the themes with which this book is concerned, wealth and power in a colonial context, for over a decade now. This book, dealing with the richest settlers in Canterbury and Otago from the 1840s to 1914, is a much- expanded version of the doctoral thesis which I presented at the University of Otago in 1993. It is my hope that this book will contribute to an understanding of the colonial New Zealand economy, of the class structure of colonial society, of the values and perceptions of the rich, and of how the rich justified and maintained their position in colonial society. While the book is focused upon two provinces in a small settler colony, the themes are of more than regional interest. The wealthy of Canterbury and Otago were part of the revolutionary expansion of nineteenth-century capitalism and, I argue, were part of the vigorous and dynamic British middle classes who made and were made by that expanding capitalism.

Assigning this book to one of the ever-increasing number of historical specialisations will, I hope, prove difficult. Although there is much in this book about rural history, it is not rural history; much about family history, it is not family history; much about gender and colonisation, it does not fit that genre; much about political history, it does not fit there either. Various themes have appeared in journals devoted to historical geography, regional studies, business history, as well as national journals of history. In the end the approach taken here is similar to that suggested by Keith Wrightson as appropriate for the study of economic history; it is an approach which emphasises the social, cultural and political contexts of economic activity and is concerned with not so much of a special class of facts as of all the facts of a nations history from a special point of view.

There are one or two points about sources and method which I would like to note. The footnotes to each chapter and the bibliography at the end of the book give the detailed citations for the sources on which this study rests. That this book owes much to the work of many other scholars, in New Zealand, Australia, the United States, Canada, England, and Scotland, will be obvious. In terms of the archival sources, two above all stand out. One is the wills of the 1042 rich settlers discussed here. A number of scholars have used probate valuations as evidence for the structure of wealth in various societies, and inventory lists have been used to reconstruct material culture and household economies in a number of studies. I have found probate files enormously rich not only in terms of the quantitative information they present on wealth, but also in terms of the insight they provide into family life and the values of the colonial wealthy. The other source which stands out as fundamental to much of this book is the National Mortgage and Agency Company records, held in the Hocken Library. This enormously comprehensive collection provides through the private letterbooks of the Companys exceptionally astute General Manager, J. M. Ritchie great insight into political and economic affairs from the late 1870s until 1912.

I have incurred many debts over the thirteen years during which I have worked on the ideas in this book. In working on the original thesis I was fortunate to be supervised by Professor Erik Olssen and Dr Tom Brooking in the History Department at the University of Otago. The rigorous support which I received from them was critical to the successful completion of the thesis, and its later conversion into this book. I was also fortunate to have the support and assistance of Dr Terry Hearn, at that time in the Department of University Extension, University of Otago. Terrys own familiarity with quantitative methods encouraged me in my work, and his generosity in reading a late draft was much appreciated. I owe an older debt to Dr Len Richardson, formerly of the Department of History, University of Canterbury, who not only taught me to write by supervising my MA thesis, but also generously gave the final draft of the doctoral thesis the benefit of his meticulous eye. I am also indebted to his continuing belief in the importance of historical class analysis. The late Rob Steven first taught me about class analysis, did so with considerable rigour, and I honour his memory. When the thesis was presented I benefited from the perceptive comments of Professor Russell Stone (emeritus, University of Auckland) and Professor Stuart Macintyre (University of Melbourne).

I must also thank the librarians, archivists, and custodians of documents too numerous to name individually upon whose services I have depended. The Hocken Library has been magnificent as always, as has the Christchurch branch of Archives New Zealand. In 1990 the Registrar and staff in the High Court at Dunedin willingly allowed me access to their strongroom, and left me alone with a centurys deposit of wills and dust. Their co-operation and trust was much appreciated. The Dunedin branch of Archives New Zealand subsequently acquired responsibility for these wills and for probate registers, and I thank the staff of that branch for their assistance. I am also most grateful to the archivists and curators of manuscripts and of photographs at the Otago Settlers Museum, the Canterbury Museum, and the Macmillan Brown Library at the University of Canterbury. I thank all these institutions, and Fletcher Challenge Ltd, for permission to use archives cited and quoted in this book.

Since I completed the doctoral thesis I have lectured in history at Lincoln University. Whatever the ambiguities of a historians position at a predominantly agricultural and natural-resources focused institution, it remains the case that Lincoln has done something that several other universities in New Zealand have failed to do: given me a job. For that I am grateful, as also for the support and funding in terms of conference and sabbatical leave. I thank my colleagues and students in the Universitys Human Sciences Division for their support and interest as the ideas in this book have been worked out (even if the students were sometimes a captive audience). Special thanks in this regard go to my colleagues Greg Ryan and Harvey Perkins, and to Jenny Ross, Divisional Director, who has consistently provided the practical help of endorsing applications for conference and sabbatical leave.