In 2016, I was immersed in constructing an index of English-language periodicals published in colonial-era India. Trawling through the archives, I came across the quaint sounding Feudatory and Zemindari India: An Illustrated Monthly Journal Published in the Interests of the Ruling Princes, Chiefs and Zemindars, etc . Upon diving in, it became clear that far from being some amusing gallery of exaggerated pomp and pageantry, Feudatory and Zemindari India had in fact been a significant publication, serving as a platform for voices from the semi-autonomous Native States that comprised Indian India. I was especially struck by a short article entitled The Education of the Ruling Princes: A Note by the Late Raja Sir T. Madhava Rao, which called for Maharajas ruling these principalities to be given a special education that would enable them to live up to their duties and responsibilities. Who was this highly decorated figure? And what had become of his plea?

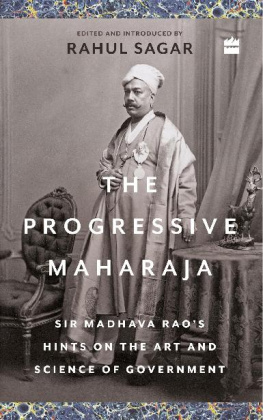

I soon learnt how little I knew about Indian India. The Raja Sir, it turned out, was one of the towering personalities of nineteenth-century India, and as Dewan of Baroda he had been responsible for its Maharajas special education. Raos enterprise was fascinating, because it appeared to be a modern example of what is known as the mirror of princesa genre of ethics in which writers directly address rulers on the tricky business of exercising power. Excited, I acquired a copy of Minor Hints , the book that apparently contained a facsimile of the lectures that Rao had delivered to Sayaji Rao Gaekwad, the ruler of Baroda. A swift inspection left me with mixed feelings. The content was certainly original and striking but the book itself was unpolished. It lacked an introduction, the lectures were obviously out of sequence, and there were no supporting materials. It left me with more questions than answers. What prompted the lectures? Why were they printed out of order? Did they have the intended effect?

I cast about for answers to little avail. There were a handful of marvelous works of the Native States, most notably by Robin Jeffrey, Barbara Ramusack, Ian Copland, Manu Bhagavan, Caroline Keen, and Manu Pillai, but none of these addressed Minor Hints .

Astonishing as this discovery was, it brought me no closer to figuring out the story behind Minor Hints . Seemingly at a dead end, I set the material aside. Then, a few months later, I came across yet another fascinating essay, The Constitution of Native States: An Important Memorandum of the Late Rajah Sir T. Madhava Rao. Published posthumously in 1906 in Indian Review , one of the most influential periodicals of the era, it explained why Maharajas ought to establish a constitutional order that would give them a dignified but symbolic role while placing administration in the hands of experienced and impartial officials. Like the article in Feudatory and Zemindari India , this memorandum was elegantly constructed and carefully argued. Consequently, I began to suspect that the haphazard Minor Hints was printed without Raos involvement. But, if so, then how had Raos lectures actually unfolded? Where was the original manu-script? Compelled by growing admiration for Raos intellect, I restarted the search for answers.

Since that time, I have systematically collected every available scrap of information on Madhava Rao. It has not been easy because the Native States were not always fastidious in their record-keeping, and many of the records they produced have perished due to neglect and folly. Still, with the aid of long hours in the archives, the increasing digitization of records, and a far-flung team of research assistants, I have been able to collect a very substantial number of records from libraries and archives around the world. All this has allowed me to assemble a comprehensive picture of Raos life and times, and of the Native States in which he served as Dewan.

Luckor fatehave contributed too. In October 2019, the index (www.ideasofindia.org) I had been constructing when I stumbled upon Rao, was about to launch. In search of some missing items, I double-checked the catalog of the Mythic Society in Bengaluru. I did not find the items I was looking for. Then, on a whim, I searched for items labelled Baroda. All the results were familiarexcept for one. The unusual entry was titled Read-ministration of Baroda and dated 1881. I guessed this was the widely distributed 1881 Baroda Administration Report . But, not wanting to leave a stone unturned, I asked my research assistant to call up the document. He replied a day later saying it was a lengthy handwritten document. This did not make sense because I knew the Baroda Administration Report was a printed document. Perhaps I had stumbled upon an early draft of the Report . If so, what was it doing in Bengaluru? Could you send me photographs of the first few pages of the document, I asked. A day later, the sample arrived. I could not believe my eyes: there it was, Madhava Raos original lecture manuscript! After my heart stopped pounding, I examined the document carefully. A stamp revealed that the manuscript had previously been housed in the private library of Sir T. Ananda Rao. This was none other than Madhava Raos celebrated son, who had lived in Bengaluru during his long service in Mysore, which included serving as Dewan between 19091912. By that evening I was on a flight to Bengaluru, and the next day I was at the Mythic Society where the Honorary Secretary, Shri V. Nagaraj, kindly allowed me to make an archival quality copy of the original manuscript.

And so concluded, on an unexpectedly triumphant note, my quest to uncover the story behind the article in Feudatory and Zemindari India . The fortuitous discovery at the Mythic Society confirmed that the book popularly known as Minor Hints was a sort of pirated edition, likely published by the Gaekwads aides long after Rao had departed Baroda. Having now painstakingly edited Raos lectures, I place them before the public in the form and manner they deserve. I have titled them Hints on the Art and Science of Government . Based on Raos correspondence, I believe this is the title he would have chosen for them. The laborious research undertaken over the past five years has also allowed me to definitively establish the fraught circumstances surrounding the lectures. I have summarized what I have learnt in The Progressive Maharaja , the introductory essay that opens this volume. I hope its merit is self-evident.

January 26, 2022

In the quest to recover and restore Hints on the Art and Science of Government I have incurred significant debts to a number of individuals and institutions.

It is no exaggeration to say that this volume would not exist without the research support provided by NYU Abu Dhabi. I am at a loss to express my gratitude to Herv Crs, the Dean of Social Sciences, and Fabio Piano, the Provost. They believed in my research and did everything they could to help me across the finishing line. I am also much obliged to a number of colleagues and administrators for supporting or administering the grants this volume relied upon: Hannah Brckner, Kanchan Chandra, Janet Kelly, Julie McGuire, Diana Pangan, and Katherine Stevens in the Division of Social Sciences, Nada Messaikeh and Sana Ahmed in the Office of Research Administration, and Martin Klimke and the NYUAD Grants for Publication Program. I also want to take this chance to express my thanks to Dimitri Landa, Bernard Manin, Ryan Pevnick, Peter Rosendorff, Ron Rogowski, Shankar Satyanath, Melissa Schwartzberg, and David Stasavage for recruiting me to NYU Abu Dhabi and thereby making so much possible.