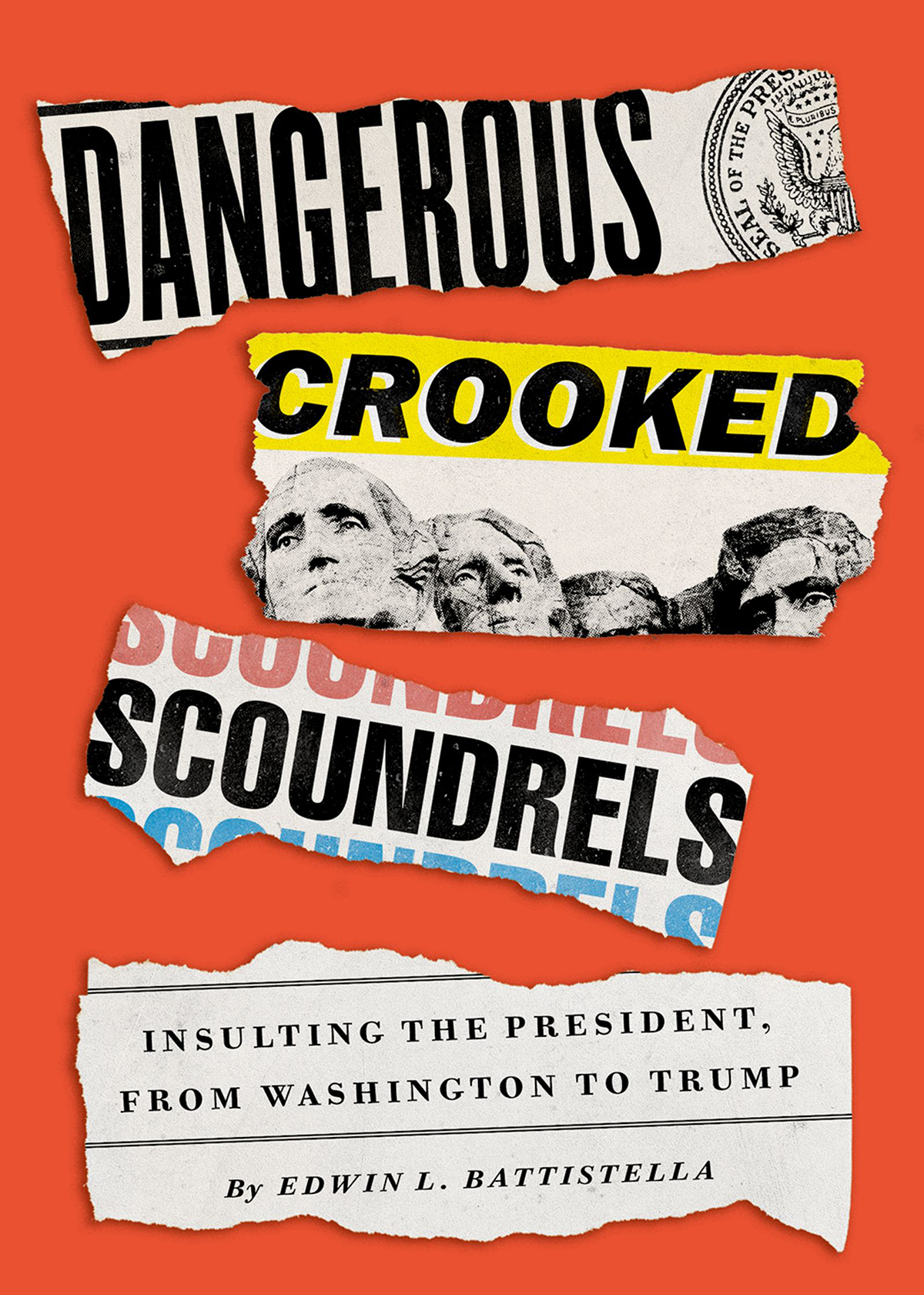

Dangerous Crooked Scoundrels

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190050900

eISBN 9780190050924

Contents

When I was growing up, trading insults was part of making your way through middle school: If they put your brain on the edge of a razor blade, it would look like a BB rolling down a four-lane highway. His parents had to put a pork chop around his neck to get the dog to play with him. If you could teach him to stand still, you could use him for a doorstop. It was wordplay, imagery, and linguistic sparringa show for an adolescent audience.

Later, I learned about Shakespearean insults (Thy tongue outvenoms all the worms of Nile), along with those of Winston Churchill (said to have described his Labour Party rival Clement Atlee as a modest man, who has much to be modest about). I also learned about Oscar Wilde (who said of Henry James that he writes fiction as if it were a painful duty) and Dorothy Parker (who described the novice actress Katharine Hepburn, appearing in The Lake, as running the gamut of emotions from A to B).

I learned about the Celtic and Germanic traditions of flyting, which involve ritualized insult. In the Norse Lokasenna (Lokis Wrangling), the god of mischief trades insults with the other gods one by one. Loki tells Bragi, the god of poetry, In thy seat art thou bold, not so are thy deeds, Bragi, adorner of benches! Flyting was a stylized battle of wits, what we might think of as a medieval rap battle. Contemporary hip-hop treats us to similar lyrics, such as Lupe Fiascos Im flying on Pegasus, you flying on a pheasant, and many more.

Wit and aesthetics can be part of an insult, but that is not always the case. An insult is ultimately an attack. The word itself, by way of French, is related to the Latin verb insultare, meaning to leap upon. In its earliest English occurrences in the sixteenth century, insult meant scornful boastingwhat today we might call trash talking. By the early seventeenth century, the word was used in the modern sense: to assail another with contempt.

As the seventeenth century gave way to the eighteenth and the thirteen North American colonies became the new United States of America, political rivals employed insults with abandon. The practice has never ceased, and this book surveys more than five hundred presidential insults from the span of US history, painting a picture of the ways in which our chief executives have been verbally attacked in their times, how they have responded, and what we can learn from it all. Todays political scene may seem to be an age of unfettered hostility, with insults regularly flying atand most recently fromthe occupant of the White House. We live in a time when presidents are called morons (a term applied to George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump) and much worse. But politics has been a rough game for a long time; our earliest presidents were attacked as pusillanimous, dastardly, and contemptible.

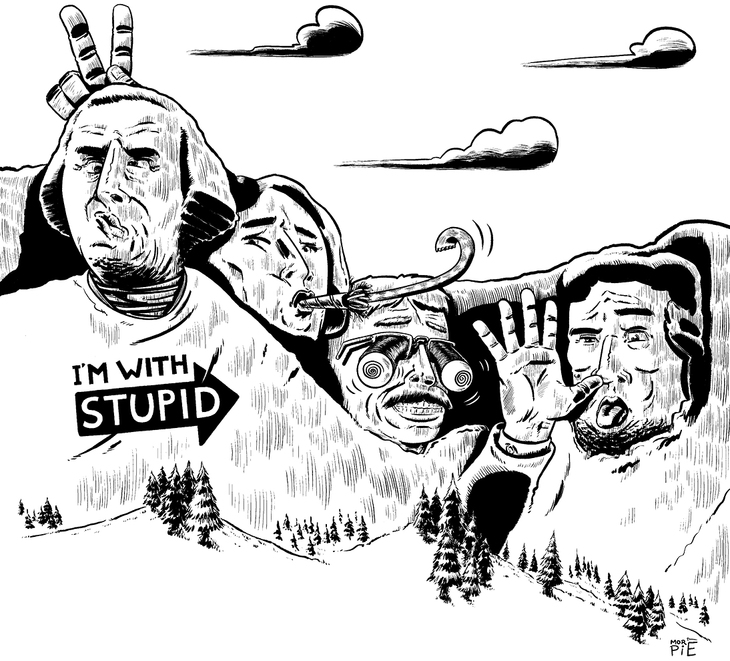

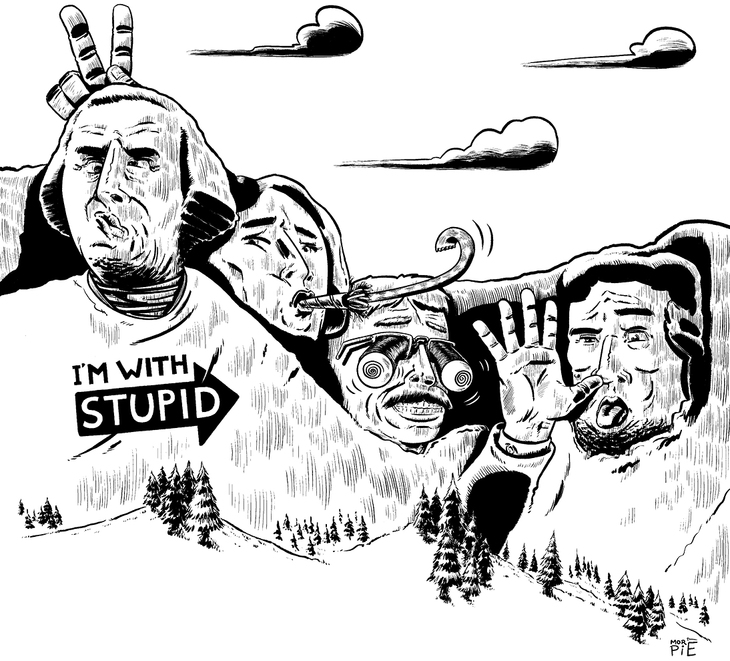

The prototypical insult is speech or action that expresses contempt or derision. It can be a gesture: the middle finger or the cuckold sign (formed by extending the index and little fingers). It can be a drawing, such as Garry Trudeaus depictions of Bill Clinton as a waffle and George W. Bush as an asterisk under an empty cowboy hat. It can be a single phrase or even just a word (usually a noun such as buffoon, fascist, dotard, or cretin). It can be an assertion (such as Salmon P. Chases observation that Grant is a man of vile habits, and of no ideas), a harsh description (Joseph P. Kennedys characterization of Franklin Roosevelt as a crippled son-of-a-bitch), or something more oblique (Lyndon Johnsons observation that Gerald Ford played too much football with his helmet off).

First, however, I include some comments about how insultspolitical insults specificallywork as a genre of verbal behavior.

An insult is different from a criticism. You might be critical of a public figureof anyone reallywithout insulting that person. When Tennessee senator Bob Corker said, The president has not yet been able to demonstrate the stability, nor some of the competence that he needs to demonstrate in order to be successful, he was critiquing Donald Trump, not insulting him. Trump may have been offended by Corkers remarks, but being offended is different from being insulted. The intention to disrespect or demean is key to insulting someone.

Of course, intentions are often in the eye of the beholder, so the distinction between being insulted and feeling insulted tends to get blurry and to blur the distinction between critique and insult. But not always; a few months later, when Corker referred to the White House as an adult day-care center, the intention to insult was clear.

Setting, tone, and harshness of language often separate an insult from a criticism or disagreement. A political adversary may dispute a claim in any number of ways, but the person who shouts You lie! in the middle of a speech is delivering an insult. Thats what South Carolina representative Joe Wilson did when Barack Obama was giving his 2009 State of the Union Address. Wilsons breach of decorumin effect calling the president a liarwas condemned by members of both parties, and he apologized for his lack of civility. Wilson was denouncing the president by interrupting with a public condemnation. Not every rebuke or condemnation counts as an insult, but Wilsons shouting, interrupting, and disrespectful language made the comment an insult, not simply an expression of disagreement. The vehemence and tone of Wilsons You lie! established an intent and turned the rebuke into an insult.

Intent also allows neutral terms to be perceived as insults, especially when there is an audience prepared to take them that way. We see this with the repositioning of words such as liberal, feminist, evangelical, and corporate as terms of abuse. This is the case also with so-called racial and ethnic dog whistles, coded characterizations that play to prejudices. When former senator Bob Kerrey referred to candidate Barack Hussein Obama and said that he liked the fact that his father was a Muslim and that his paternal grandmother is a Muslim, he was ostensibly making a neutral or even positive observation. But in the context of rumors that Obama was a secret Muslim planning to bring jihad to the United States, the comment was a dog whistle. Kerrey later wrote to Obama, explaining, I answered a question about your qualifications to be president in a way that has been interpreted as a backhanded insult of you.