ALA Editions purchases fund advocacy, awareness, and accreditation programs for library professionals worldwide.

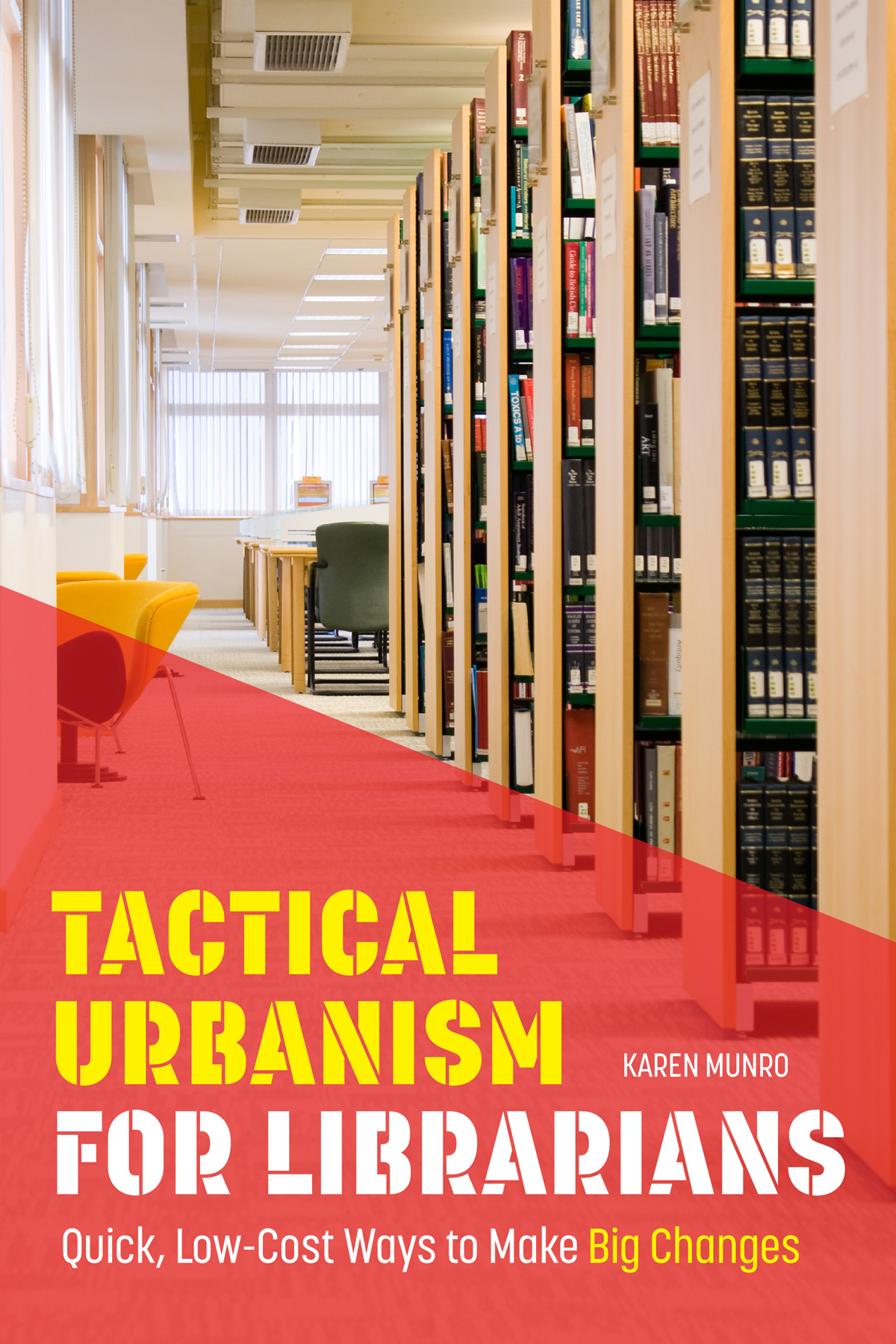

KAREN MUNRO is head of the University of Oregon Portland Library and Learning Commons. Previously she was e-learning librarian at the University of California, Berkeley and literature librarian at the University of Oregon. She has an MFA from the University of Iowa Writers Workshop and an MLIS from the University of British Columbia. She publishes and presents often on topics related to library design and outreach to users, particularly those in the fields of architecture and design.

2017 by Karen Munro

Extensive effort has gone into ensuring the reliability of the information in this book; however, the publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein.

ISBNs

978-0-8389-1558-5 (paper)

978-0-8389-1584-4 (PDF)

978-0-8389-1585-1 (ePub)

978-0-8389-1586-8 (Kindle)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Munro, Karen, 1973- author.

Title: Tactical urbanism for librarians : quick, low-cost ways to make big changes / Karen Munro.

Description: Chicago : ALA Editions, an imprint of the American Library Association, 2017. | Includes .

Identifiers: LCCN 2017007493| ISBN 9780838915585 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780838915844 (PDF) | ISBN 9780838915851 (ePub) | ISBN 9780838915868 (Kindle)

Subjects: LCSH: Library planning. | Libraries and community. | Libraries and metropolitan areas. | LibrariesSociological aspects. | LibrariesCase studies. | Organizational change. | City planningCitizen participation. | Urban renewalUnited StatesCitizen participationCase studies.

Classification: LCC Z678.M96 2017 | DDC 025.1dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017007493

Cover image Lwzfoto/Adobe Stock.

For my family

Contents

My sincere thanks to all the librarians who spoke with me about the projects in this book, to the resource-sharing and interlibrary loan librarians and library staff who helped me amass the vast number of books and articles that I read as background, to everyone who published their work so I could find out about it in the first place, and to everyone who keeps trying out cheap, quick, creative ways to make libraries work better for everyone.

An Introduction to Tactical Urbanism

Once Upon a Time in DUMBO...

I n spring 2007, a truck pulled up to a small, garbage-strewn parking lot under the Manhattan Bridge in Brooklyn. The lot was described by people who knew it as forlorn and barren (Chan 2007; Naparstek 2007). It had space for about a dozen cars on an ungainly triangle of land where Pearl Street and Anchorage Place meet, just a few blocks south of the East River. New York is full of these oddly shaped bits of wasteland, many of them created when long avenues were overlaid on the existing street grid. In this one, Anchorage Place follows the diagonal path of the Manhattan Bridge Lower Roadway and its overpass, which looms over the lot on its west side. It was a valuable little piece of the DUMBO neighborhood in Brooklyn, but it wasnt a pretty spot, or one where most people would want to linger.

The truck was from the New York City Department of Transportation. It carried a load of green paint, and its crew had specific instructions about how to apply it. They unloaded their gear and started to work.

By August the cars were long gone. The concrete triangle of the lot was painted bright grassy green, shade umbrellas and public seating had been installed, and planters overflowed with trees and flowers. In lieu of a raised curb, a double white line separated the new pocket park from the streets around it, with enormous granite blocks acting as bollards. Local artists had brought sculpture and distinctive handmade furniture. A local food truck began visiting the park during weekday lunch hours. The former parking lot even got a new namethe Pearl Street Triangle.

And the work didnt end there. In March 2010, the neighborhood held an Ideas Competition to improve the park even more (dumbonyc 2010). Eight proposals suggested everything from adding another subway stop for the elevated line that runs above the park to creating tiered amphitheater seating for public performances to transforming the triangle-shaped park into an enormous interactive piano keyboard. Thanks to an arts grant, in 2012 the green paint was replaced with an enormous mural by artist David Ellis, depicting a pair of giant hands supporting a brightly colored body. In 2016, a weekly farmers market moved in, bringing everything from fresh produce and eggs to old-fashioned-style barrel pickles (Frishberg 2016).

What started with a few buckets of green paint and a few extra granite blocks from the Washington Bridge has become an urban oasis and the heart of the DUMBO community (DUMBO Improvement District 2012, 2015). Happily, the park seems to prove the truth of the Hollywood clich: if you build it, they will come.

But theres more to the story.

The success of the Pearl Street Triangle, and dozens of other pocket parks like it throughout New York City, owes as much to careful planning, solid partnerships, and visionary leadership as it does to grassroots, can-do creative spirit. It owes a great deal to the big-picture strategies of the New York City Department of Transportation and to Mayor Michael Bloombergs PlaNYC program, which aims to create more open public spaces throughout the city (Chan 2007). It owes much to the DUMBO neighborhoods Business Improvement District, which brokered deals with local artists and restaurants to make the park lively and distinctive. But it owes perhaps the most to the controversial work style of New York Citys transportation commissioner from 2007 to 2013, Janette Sadik-Khan.

It was during Sadik-Khans term that the Pearl Street Triangle was realizednot just conceived, described, or approved, but cleaned up, painted, planted, and furnished. It was during her term that more than sixty public parks and plazas were created across the city, most in spaces that were considered ungainly, inefficient, or useless (Sadik-Khan 2016). And although Sadik-Khan made a lot of nice places for New Yorkers to sit, shes perhaps even better known for getting them onto their bikes.

During her seven years with the Department of Transportation, Sadik-Khan claims that the city added almost four hundred miles of bike lanes (Lindsey 2015). During the same period, surveys show that bicycle commuting rose from just under twenty thousand to over thirty-six thousand cyclists (Flegenheimer 2013). In 2007 the New York City Department of Transportations twelve-hour Midtown Bicycle Count, which counts bicyclists passing predetermined points throughout the city on a given day between 7 a.m. and 7 p.m., averaged 13,205 trips per year (New York City Department of Transportation 2015). By 2013 that same twelve-hour count had leaped to over twenty-one thousand trips. Broadway Avenue, one of the worlds most famous and iconic streets, closed half its lanes to car traffic to make room for a bike path and a pedestrian zone (Neuman 2008). Times Square, the garish neon heart of the city, was closed to traffic completely and became a pedestrian haven.

How did Sadik-Khan do it? How did she change one of Americas densest, most car-congested cities into a place riddled with bike lanes and neighborhood parks? How did she overcome the New York City attitudes, temperaments, and belief systemsnot to mention the entrenched agency officials and taxi unionsthat make a two-wheeled, park-loving revolution seem not just unlikely but almost impossible?

Next page