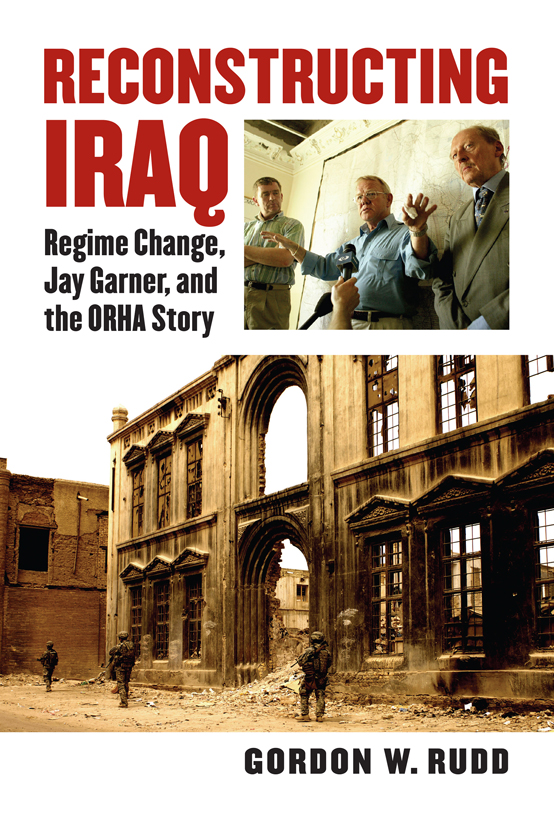

RECONSTRUCTING IRAQ

MODERN WAR STUDIES

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

J. Garry Clifford

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

Dennis Showalter

David R. Stone

Series Editors

RECONSTRUCTING

IRAQ

REGIME CHANGE, JAY GARNER,

AND THE ORHA STORY

GORDON W. RUDD

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KANSAS

2011 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rudd, Gordon W., 1949

Reconstructing Iraq : regime change, Jay Garner, and the ORHA story / Gordon Rudd.

p.cm. (Modern war studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7006-1779-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-7006-2737-0 (ebook)

1. Postwar reconstructionIraq. 2. Iraq War, 2003 3. Office for Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance. 4. Garner, Jay Montgomery, 1938 I. Title.

DS79.769.R84 2011

956.704431dc22

2010048252

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in the print publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The United States invaded Iraq in 2003 to change the regime of Saddam Hussein, prepared for half the job. In less than a month, coalition forces defeated the Iraqi army and drove Saddam into hiding. Yet history shows that regime change must include regime replacement as well as regime removal. American political leaders misread the nature of the Iraqi people and state, and they failed to make adequate preparations to put a new government in place. The loss of lives, treasure, time, and American prestige was a magnitude greater than those leaders anticipated.

The ad hoc organization formed to manage regime replacement was the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, which came to be called ORHA. The leader was Jay Garner, a retired Army lieutenant general recalled to government service. This is the story of ORHA and Jay Garner, a figure both heroic and tragic, a charismatic leader of great enthusiasm and drive who, in good faith, took on a task of grand proportions and was poorly served by those who chose him and sent him to Iraq.

The rationale for regime change included Iraqs alleged weapons of mass destruction, the view that the Iraqi regime supported terrorism, and other acts that were said to cause regional instability. Yet Iraq had not committed any specific actnothing comparable to the invasion of Kuwait in 1990that required the United States to invade in 2003.

The invasion of Iraq was elective and deliberate, following military planning that had been conducted for over a decade. In contrast, the planning for regime replacement was haphazard and grossly inadequate, with far less time for study and debate. Just two months before the invasion, Jay Garner was asked to put together the organization that would execute that planning for the post-conflict phase in Iraq.

In January 2003, I received a call from Jay Garner, asking meas a historianto assist him on a project he could not discuss on the phone. I knew Garner as a key figure from Operation Provide Comfort, a 1991 humanitarian intervention to assist Kurdish refugees in northern Iraq following Desert Storm. I had written a book on Provide Comfort based on interviews with many participants of the operation, including General Garner.

I greatly admired Garner, and sowith no sense of the scope of his projectI told him that I would be happy to assist him. Within a week, I found that it would be a full-time endeavor, and I asked those for whom I worked at the U.S. Marine Corps School of Advanced Warfighting in Quantico, Virginia, for a leave of absence to join ORHA. My rationale, beyond assisting Garner, was that ORHA would be a case study in interagency operations and that the experience would yield material we could add to the curriculum at Quantico. My supervisors thus released me from my duties for eight months in 2003 and then for several months more the following year.

When I arrived at the Pentagon that January, Garner had six people with him. I watched as ORHA grew to almost two hundred by mid-March when we flew to Kuwait, then doubled in size by the time we went into Iraq in April. Garner knew no more than a dozen of them prior to their arrival in ORHA. Most of us came from government agencies, mainly from the Departments of Defense and State, and from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). There were also representatives from the Departments of Treasury, Commerce, Agriculture, Justice, and Energy and from the CIA. In the beginning, half of those in ORHA were military personnel from the four American services. As more civilians were added the balance shifted. A few people from the United Kingdom joined as we left Washington.

While there was a growing non-American contingent, ORHA was mainly a U.S. interagency organization, with an exceptionally diverse group of people, just the sort I wanted to study. I had the opportunity to observe their activities in the Pentagon, Kuwait, Baghdad, and other places in Iraq. I got to know some of them well and many became friends. Some were ill suited for the tasks before them and it was sad to see them stumble. Others adapted remarkably well, went into harms way without apparent reservation, and gave their country and Iraq their best efforts. Sometimes their best efforts were adequate; often they were not.

Garner was replaced by Ambassador L. Paul Bremer III on 12 May 2003. After a three-week transition, Garner left Iraq on the first of June. I rode with him from Baghdad but chose to remain behind at al-Hilla in southern Iraq as Garner continued home. Many of those in ORHA were absorbed into Bremers Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), and I wanted to see how that would work. I found that transition neither smooth nor thoughtful, and that is part of the ORHA story. At the end of the summer I left Iraq to resume teaching at Quantico, but returned twice: for a month at the end of 2003 and again in mid-2004 to observe CPA transfer its functions to a new American embassy and to the interim Iraqi government.

My work has been twofold. My first task was to document the experience in the field. For that, I conducted some 280 interviews, many with members of ORHA and CPA while they were serving in Iraq. However, their experiences led to questions that could not be answered there and I have spent much of the past several years conducting interviewsin the United States, in the United Kingdom, and elsewhereto enlarge upon the context for ORHA. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed, to be placed in appropriate archives for those who would study ORHA and regime change in Iraq.

My second task has been to capture the story of ORHA. Most of this book is devoted to the ORHA story; the Prologue and

Thus follows a prologue that reviews the American post-conflict experience with some attention to World War II. Planning for Iraq included frequent references to American experiences with Germany and Japan. But those were long-term occupations, whereas the focus for Iraq was on liberation. Other experiences, which might have been studied from that periodthe liberations of Italy, France, Austria, Korea, and the Philippines (all with aspects of occupation)arguably had more relevance for Iraq.

Next page