Contents

Page List

Guide

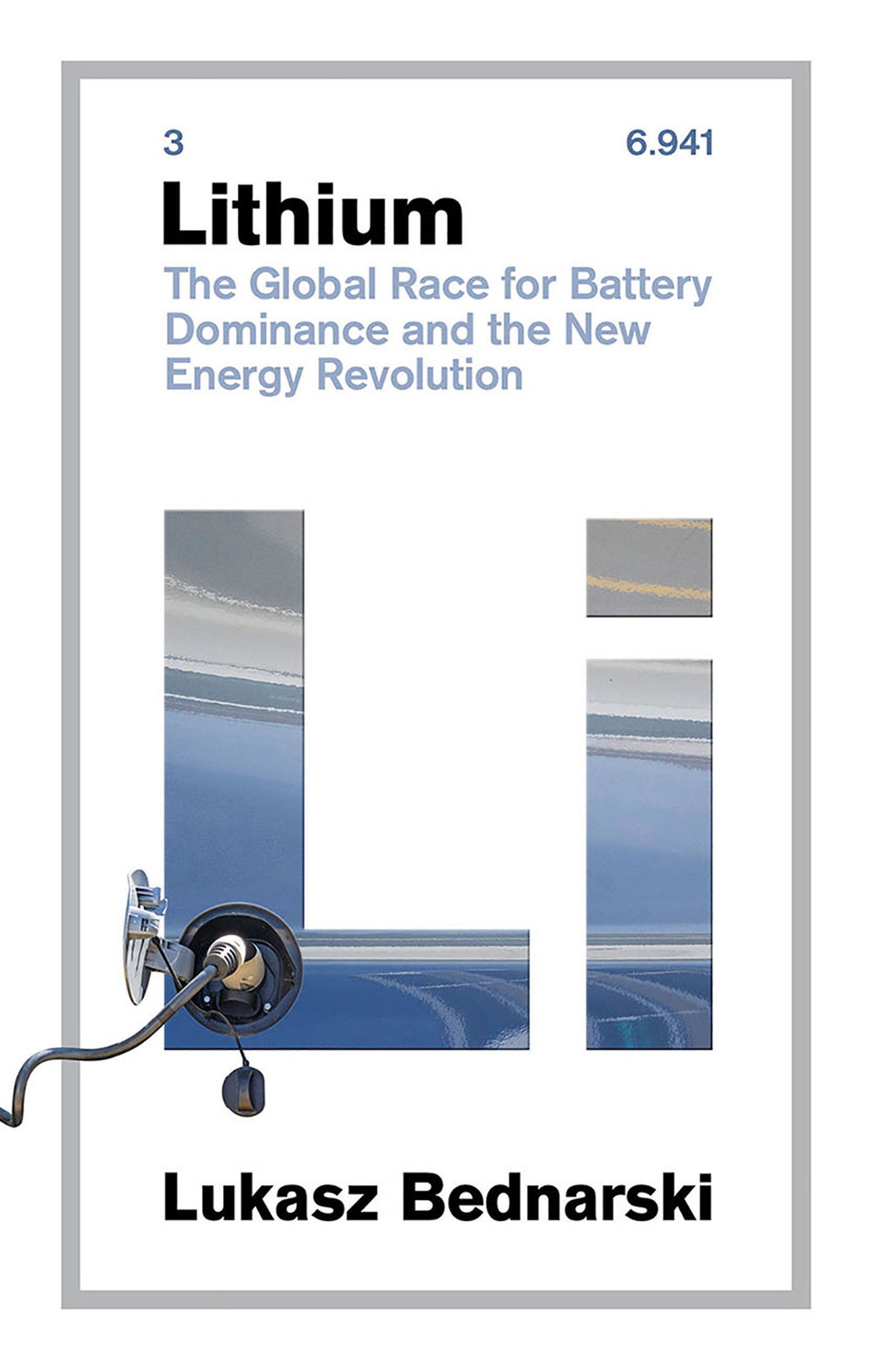

LITHIUM

LUKASZ BEDNARSKI

Lithium

The Global Race for Battery Dominance and the New Energy Revolution

HURST & COMPANY, LONDON

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

83 Torbay Road, London NW6 7DT

Lukasz Bednarski, 2021

All rights reserved.

Printed in Scotland

The right of Lukasz Bednarski to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787385634

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources.

www.hurstpublishers.com

To my partner, Anna, who always believed in this project, and to my parents and grandparents, who taught me the joy of reading

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

If you look at the periodic table, lithium takes the third place out of 118 elements. This hardly seems a compelling reason to read a book about it. But despite its simplicity, with only three protons, this metal is redefining the way we think about energy in the twenty-first century.

Renewable energy produced from solar panels and wind farms has been with us for decades. In 1979, President Jimmy Carter installed solar panels on the White House, to improve its overall energy efficiency, and to promote solar panel use among the public. Until now, the advantage that fossil fuels had over renewables derived from their ability to double as an energy storage medium. By refuelling your tank, you store a lot of energy within a small space that can be harnessed to do work; namely, to power your car. Until fairly recently you were not able to do the same with energy from renewables. Lithium changed that. Lithium-based batteries are the last missing piece in the puzzle of a closed system based on renewable energy.

We are at the very beginning of a groundbreaking change, where energy from renewable sources can be stored to run your car and your portable electronic devices. One day, this green energy will power ocean-going vessels carrying consumer goods you use every day, and let you take off for a holiday without worrying about the planes carbon footprint. It has not happened yet, but, to paraphrase Amaras law, we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short term and underestimate its impact in the long run.

Around 79 per cent of crude oil currently consumed in the world is used to power cars, planes and ships. Most industry observers have stopped asking whether EVs will replace conventionally powered vehicles. Instead, they are asking when.

The shift from fossil-fuel-propelled engines to the lithium-ion battery is the biggest change in transportation since the end of the nineteenth century, when Carl Benz built the first gasoline engine. It is having a deep impact on industries, national economies, strategic security interests and the struggle to stop or at least minimize the effect of climate change. We are not talking about the distant future, either. The book focuses on exploring the changes that have already taken place as well as those that will happen in front of our eyes, leaving speculation about the world thirty years from now to futurologists.

Large corporations and technocratic authoritarian governments both hold enormous sway in the current political and economic environment, no matter whether we like it or not. The future is being created by government and corporate actors who think in terms of decadesoften in the form of five- to ten-year plans, supported by consulting experts research forecasts. Their targets are being met or not, and progress is more or less carefully evaluated. Made in China 2025, a strategic plan worked out by Premier Li Keqiang and his cabinet in the spring of 2015 to transition China from being the factory of the world to a technological powerhouse, turned the EV, battery and lithium industry into a top national priority.

A book like this could not have been written at the time when China and Volkswagen were revealing their strategies to the world. Then, demand for lithium was not high enough to support the elements claim of becoming the new oil. Until 2015, lithium production was more focused on ceramic and glass production than on supplying the battery industry. Nevertheless, brains in the Communist Party of China, or, for that matter, at Volkswagen, must have foreseen the strategic role of lithium when drafting their 2025 plans.

Development of the lithium and battery industry has never lost pace since its early days. The demand for lithium-ion batteries grew by more than 30 times from 2000 to 2015, Even now, amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, the companies in this industry make bold decisions on spending tens and hundreds of millions of dollars to build up capacities to satisfy the demand anticipated in five or ten years time.

They are turning the crisis into an opportunity to gain an edge over more cautious competition, betting on the electric world that is still yet to come.

As the history of the oil industry has been centred on the Western world and the Middle East, with the United States of America playing a leading role, so the lithium industry centres on Asia and Latin America, with a leading role for China. The roles that China, South Korea and Japan play in the lithium-ion-battery industry is yet another sign among many that the centre of economic and political influence is moving from the West to Asia.

The need to secure or maintain sources of hydrocarbons has been driving Western political decisions over many decades, from the encouragement, by the British government, of the adventurist William Knox DArcys search for oil in Persia in the early 1900s to, most recently, the controversies around Gazproms Nord Stream 2 pipeline. It would be hard to explain the history and current state of the oil industry without references to European, American or Middle Eastern politics. Thus, the book that you hold in your hands will draw substantially on Asian current affairs, to paint the picture of the lithium industry within its Asian context.

As the American version of capitalismcharacterized by individual initiative and a free marketleft its footprint on the oil industry, so the Asian version of capitalismcollective effort and priorities dictated from the topis leaving its mark on the battery and lithium industry as it expands.

Even though lithium-ion batteries were first commercialized in Japan, by Sony Corporation, and Japan continues to have a certain edge in the production of key battery components, the book starts in China. China may not match Japan in the quality or elegance of its technological solutions, but it does a great job in bringing the new-energy revolution to the masses, here and now. China is not waiting for battery technology to achieve its peak before starting widespread EV adoption.

The whole system is already in place to serve the industry and customers. Lithium and other key raw materials are mined, processed into chemicals, transformed into components and installed in domestically produced batteries without leaving Chinas borders at any stage. The batteries go on to power domestic brands of EVs that, as a Westerner, you have probably never heard of. The great thing for the industry observer is that most stages of the production process are carefully monitored by the state, which provides a level of transparency that you would not find even in the European Unions centralized market.