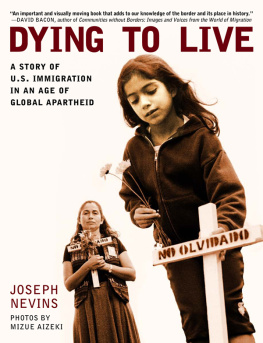

Joseph Nevins - Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid

Here you can read online Joseph Nevins - Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: City Lights Publishers, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid

- Author:

- Publisher:City Lights Publishers

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

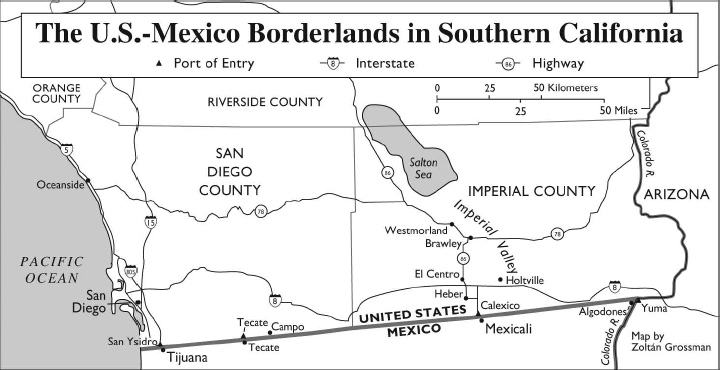

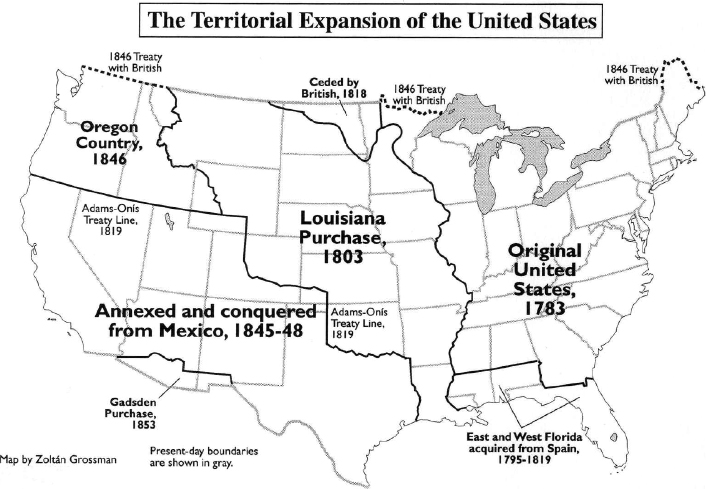

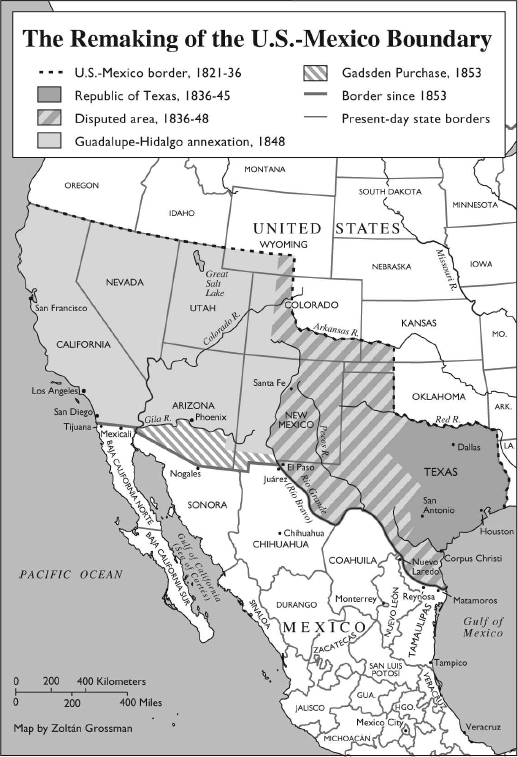

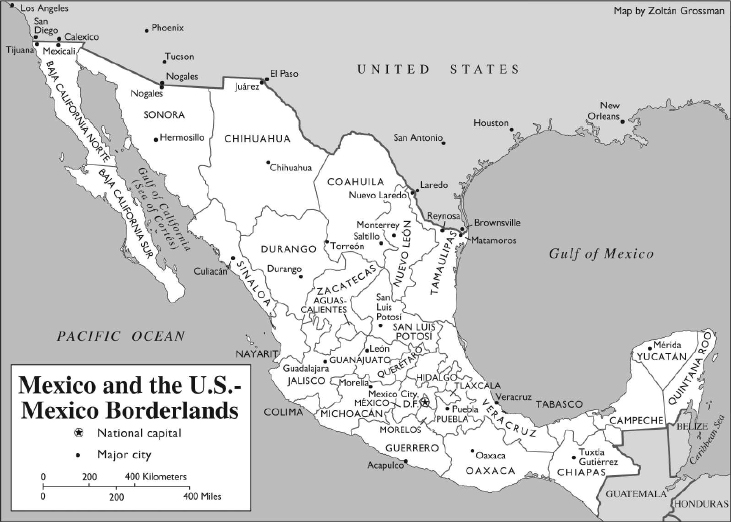

A compelling account of U.S. immigration and border enforcement told through the journey of one man who perished in Californias Imperial Valley while trying to reunite with his wife and child in Los Angeles. At a time when Republicans and Democrats alike embrace increasingly militaristic border enforcement policies under the guise of security, and local governments around the country are taking matters into their own hands, Dying to Live offers a timely confrontation to such prescriptions and puts a human face on the rapidly growing crisis. Moreover, it provides a valuable perspective on the historical geography of U.S./Mexico relations, and immigration and boundary enforcement, illustrating its profound impact on peoples lives and deaths. In the end, the author offers a provocative, human-rights-based vision of what must be done to stop the fatalities and injustices endured by migrants and their loved ones.

Praise for Dying To Live:

In Dying to Live, Joseph Nevins and Mizue Aizeki have produced an important and visually moving book that adds to our knowledge of the border and its place in history. Nevins painstaking research documents the development of the Imperial Valleyits industrial agriculture, its divided cities, and the chasms between rich and poor, Mexican and anglo, that have marred its growth. Through the valley runs the border, and Nevins accounts of the growth of border enforcement on the U.S. side, and the racism of its legal justifications, will be a strong weapon for human rights activists. Mizue Aizeki takes her camera and tells the story of Julio Cesar Gallegos, who died in the desert trying to make it across. Her images of the stacked bodies of border crossers held in refrigerator trucks, and the barrenness of the ocotillo cactus on the flat hardpan are eloquent testimony to the terrible risks and human costs imposed on migrants. Her beautifully composed portraits of Gallegos family make a direct appeal to the heart in a way that words cannot. And her documentation of border protests and immigrant rights demonstrations, including the rows of jugs of water put out in the desert to save lives, are all compelling evidence that there is a struggle going on to halt the human rights crisis she and Nevins document.

David Bacon, author of Communities Without Borders: Images and Voices from the World of Migration

Joseph Nevins blows the cover off the scapegoating of illegal immigrants by meticulously and grippingly compiling the history of why so many try to come to the U.S. and, tragically, why so many die. This book strikes at our very moral core.

Deepa Fernandes, author of Targeted, Homeland Security and the Business of Immigration

A fierce and courageous denunciation of the foul politics of immigration and the two-thousand mile tragedy of the Mexican border, snaking its way between two worlds, two nations, separated at birth but forever joined at the hip. Starting from one mans blackened corpse, the tale wends its way across the desert of racial amnesia to reveal the sources of Americas reactionary (and futile) attempt at closure of a porous frontier. Deftly stitching together disparate times and placesfrom the Imperial Valley to Zacatecas to Mexicali and back to East L.A.Nevins and Aizeki weave a memorial quilt to the hundreds of innocents in unmarked graves.

Richard Walker, professor of geography, UC Berkeley, and author of The Conquest of Bread and The Country in the City.

Dying to Live is a compelling, perceptive and invaluable book for our times. Our new apartheid, as explored here, is as bleak and hostile as the landscapes in which people lose their lives...

Joseph Nevins: author's other books

Who wrote Dying to Live: A Story of U.S. Immigration in an Age of Global Apartheid? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.