Kilowatts and Crisis

Development, Conflict, and Social Change Series

Scott Whiteford and William Derman Michigan State University Series Editors

Kilowatts and Crisis: Hydroelectric Power and Social Dislocation in Eastern Panama, Alaka Wali

Deep Water: Development and Change in Pacific Village Fisheries, Margaret Critchlow Rodman

The Spiral Road: Change in a Chinese Village Through the Eyes of a Communist Party Leader, Huang Shu-min

Struggling for Survival: Workers, Women, and Class on a Nicaraguan State Farm, Gary Ruchwarger

Ancestral Rainforests and the Mountain of Gold: Political Ecology of the Wopkaimin People of Central New Guinea, David Hyndman

To my parents Kameshwar C. Wall and Kashi Wali and to my husband, Richard Hubbard with love and gratitude

Kilowatts and Crisis

Hydroelectric Power and Social Dislocation in Eastern Panama

Alaka Wali

First published 1989 by Westview Press, Inc.

Published 2018 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1989 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wali, Alaka.

Kilowatts and crisis.

(Development, conflict, and social change series)

Includes index.

1. Land settlementPanamaChepo River Valley Region.

2. Water resources developmentSocial aspectsPanama

Chepo River Valley Region. 3. Chepo River Valley Region

(Panama)Economic conditions. I. Title. II. Series.

HD384.C47W35 1989 330.97287 86-22405

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-01168-0 (hbk)

The debt of gratitude accumulated while I researched and wrote this book is enormous. I have benefitted from advice and assistance at every phase. Most of all, I am grateful to the people of the Bayano region. Their warmth, openness and willingness to share their memories and experiences with me made field research a time of personal enrichment and growth. I would particularly like to thank the families I lived with in Ikanti, Piryati, Ipeti, Kipin Yala, and Tort, who took care of me and taught me with gracious hospitality and genuine friendship.

This book, I hope, fulfills my promise to tell their story--the pain of resettlement and the courage with which they responded to the threat to their land and livelihood.

In Panama, I also received help from many other people. Marcia Arosemena de Arosemena, Marcela Camargo and the late Dr. Reina Torres de Araz of the Direccin Nacional de Patrimonio Histrico gave invaluable guidance and shared their own research experiences. Alexander Moore, Francisco Herrera and Luz Graciela Joly, provided crucial advice and direction.

Additionally, the staff of the Gorgas Memorial Laboratory, especially Drs. Carl Johnson, John Petersen, William Reeves, Rolando Saenz and Abdiel Adames, facilitated research by providing transport, medical supplies and material resources. Thanks also to Norberto Guenrero and his wife, Rolando Hinds and Luis Obaldia for companionship.

I owe a profound thanks to Chris N. Gjording, S.J. who as a fellow student and fieldworker hashed through troublesome aspects of the research and shared insights. He and I worked together to develop the history of Panama presented in .

The research presented here was financed with a Fellowship from the Inter-American Foundation (Rosslyn, Virginia)--recently the Foundation sent me back to Panama, giving me the opportunity to update the original material. Lambros Comitas, George Bond, Joan Vincent, Conrad Arnsberg and Harriot Klein constructively criticized earlier drafts and provided intellectual guidence.

Scott Guggenheim and Jane Slacter also read drafts and made editorial corrections. Shelton Davis, who first drew my attention to the plight of the people of the Bayano, continues to be a source of inspiration. My gratitude to James Howe, ethnographer par excellence, is not expressed in a few words. I casually asked him to make a few suggestions and I received voluminous notes and comments, careful review of facts and bibliographical references that helped me update and substantially revise my original work.

Stephanie Smith and Gordon Karim did the bulk of the typing and formatting. Kim Shelsby and Sandra Goldman did the cartographic work. The editors at Westview Press patiently put up with delays and postponements.

Finally, the support of family is something anthropologists never take for granted. My parents, sisters and in-laws gently but firmly applied loving pressure to "get the thing done". My deepest debt is to my husband, Richard Hubbard. He took a leave from his own studies to accompany me to Panama and has been unfailing in his support ever since.

As grateful as I am to all these people, I take full responsibility for the contents of this book.

I have tried to keep at a minimum the use of Kuna, Ember and Spanish words to facilitate reading. Where their use is unavoidable, I have underlined them and defined them at their first appearance. After that, they appear as regular text. Kuna orthography follows Howe (1986). Kuna vowels are pronounced as those of Spanish. The p, t, and k are pronounced similarly to the English b, d, and g. The pp, tt, and kk are pronounced similarly to the English p, t, and k.

While the locales have not been disguised, the names of individuals (except public figures) have been changed to protect their privacy.

All translations of quotes from Spanish and Kuna statements, published articles and documents are mine.

1

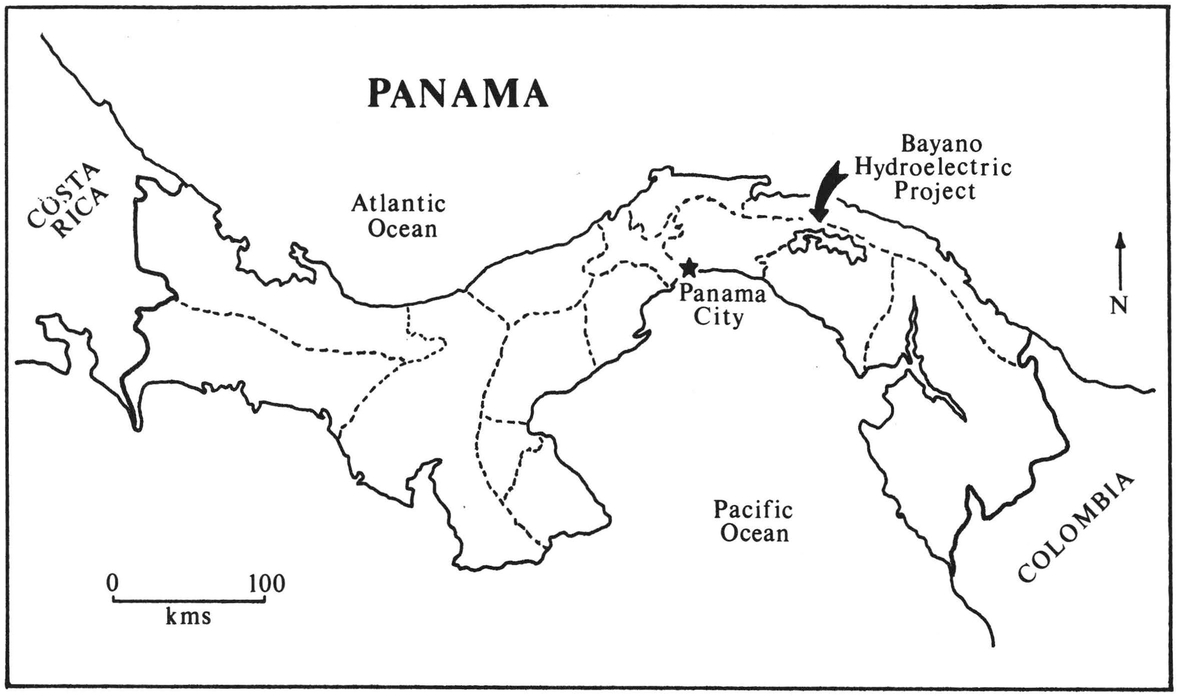

Introduction: The Bayano Hydroelectric Complex

On a muggy day in March of 1976, under gathering rainclouds, a large crowd of Panamanian government officials, international dignitaries, diplomats, and local citizens congregated at the top of a massive concrete and steel structure, gleaming and cold in the midst of the lush tropical forest of eastern Panama, part of the region known as the Darin. The Bayano Hydroelectric Complex, one of four hydroelectric development projects planned by the Panamanian government, was complete at last. Below the crowd the turbulent waters of the Bayano River, one of three major rivers of the Darin, rushed through the deforested basin which was to be the dam's reservoir towards the soon-to-be closed gates of the huge dam.

After numerous and lengthy ceremonial speeches marking the event, the gates of the dam finally began to close. As water filled the reservoir, General Omar Torrijos, the country's charismatic, popular leader ran down the hill and jumped fully-clothed into the newly-forming lake.