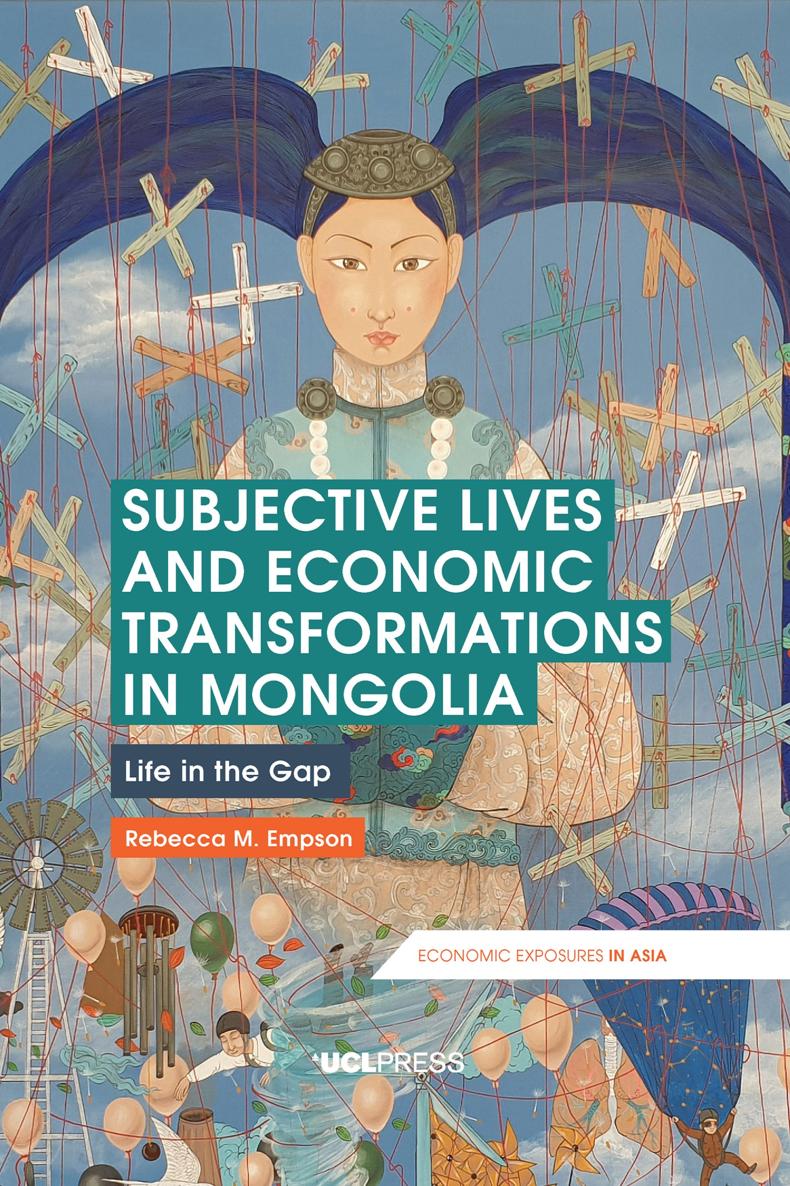

Subjective Lives and Economic Transformations in Mongolia

ECONOMIC EXPOSURES IN ASIA

Series Editor:

Rebecca M. Empson, Department of Anthropology, UCL

Economic change in Asia often exceeds received models and expectations, leading to unexpected outcomes and experiences of rapid growth and sudden decline. This series seeks to capture this diversity. It places an emphasis on how people engage with volatility and flux as an omnipresent characteristic of life, and not necessarily as a passing phase. Shedding light on economic and political futures in the making, it also draws attention to the diverse ethical projects and strategies that flourish in such spaces of change.

The series publishes monographs and edited volumes that engage from a theoretical perspective with this new era of economic flux, exploring how current transformations come to shape and are being shaped by people in particular ways.

First published in 2020 by

UCL Press

University College London

Gower Street

London WC1E 6BT

Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk

Text Rebecca M. Empson, 2020

Images Copyright owner named in captions, 2020

Rebecca M. Empson has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library.

This book is published under a Creative Commons 4.0 International licence (CC BY 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work, provided that attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Empson R.M. 2020. Subjective Lives and Economic Transformations in Mongolia: Life in the Gap. London: UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787351462

Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

ISBN: 978-1-78735-148-6 (Hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-78735-147-9 (Pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-78735-146-2 (PDF)

ISBN: 978-1-78735-149-3 (epub)

ISBN: 978-1-78735-150-9 (mobi)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787351462

Each of the chapters is prefaced with an image from Nomin Bolds series, depicting five Mongolian women as the guardians of the five elements (one of which is reproduced on the cover). The figures surrounding the women are dependent on them as their marionettist. All images are Nomin Bold and are used with kind permission.

Figure 1 Earth (soil) Shoroo, by Nomin Bold, 2016. Acrylic, canvas 245 145 cm.

Figure 2 Air Agaar, by Nomin Bold, 2019. Acrylic, canvas 245 145 cm.

Figure 3 Fire Gal, by Nomin Bold, 2016. Acrylic, canvas 245 145 cm.

Figure 4 Water Us, by Nomin Bold, 2016. Acrylic, canvas 245 145 cm.

Figure 5 Wood Mod, by Nomin Bold, 2016. Acrylic, canvas 245 145 cm.

It had been three years since I was last in Mongolia, and things felt unfamiliar. The skyline was crowded by new buildings. Fashion styles had diversified. Shops and restaurants proliferated. There was also a new kind of dirty, rugged and raw side to the gloss and glamour that Mongolians are so good at upholding. As on previous visits, but perhaps more intensely simply because of the great contrasts, in 2015 I felt that I was being confronted in a somewhat dystopian way with what a capitalism of the future might look like.

Brushing up against this underside the ruthless contrast between rich and poor, the seeming absence of the state, the horrendous air pollution in the city and the ravaging of natural resources, the unequal access to medical care and the way in which people were trying to make a living on the edges of things provided a glimpse of the reverberating effects of late capitalism being felt in numerous places. Deeply destructive, uneven and desperate, it also appeared thrilling and full of potential. Cutting across this landscape of raw inequalities were individual people forging their own ethical projects that sometimes, somewhat surprisingly, seemed to flourish and grow in the cracks. Rather than a simple before and after (boom and bust, utopian and dystopian) narrative, I hope that through our attention to the lives of individuals will bring out a more complex and nuanced understanding of this time will emerge.

In retrospect, it feels easy to write about these kinds of experiences as the outcome of neoliberal policy and forms of austerity, about the discontent and short-sightedness of extractive capitalism with its focus on growth and greed. It is hard to make variegated and local stories count. One way in which I have been able to anchor my reflections in the changes I have observed in Mongolia is to focus on the different kinds of personal interventions into what seems so pervasive and predetermined. Elevating the stories of people that seem to go against the grain of what we may assume to be prevalent and dominant also becomes a political act of writing those worlds into being. In the following chapters I amplify the diversity that exists in spite of the shared sense that we are hurtling towards something anticipated and known. This is to deliberately side-step pervasive narratives of anthropogenic and economic crisis and focus instead on how we live in spite of such chaos.

*

In subsequent visits I became privy to the way in which my close female friends were reflecting and interpreting the economic, moral and political challenges they were facing. In contrast to the political rhetoric of men and the businesspeople I had worked with, many women seemed to work hard to create a space in which life could be tended to in another way. Alongside the violently fluctuating economy of the past few years, which had left some with nothing and others with more than they would ever need, these women were steering their way along a different path, which allowed them to reconsider moral, political and ethical choices about the kind of world they wanted to inhabit and the future this would mean for Mongolia as a nation.

The five women who are core to this book are all from different socio-economic backgrounds. I explore the kinds of lives they have been forging in the wake of recent economic growth and its rapid decline and the increasing questioning of belief in democracy. What this has opened up for many is perhaps not surprise at the fact that promises have not materialised (they do not bank on the fleeting promises of politicians), but a space in which to question past dreams and reconsider new ways of imagining the future. Innovative, creative and highly reflective, their views should be amplified above the dominant voices of squabbling politicians who rotate business and political alliances, trading in accusations of corruption.

To highlight this kind of heterogeneity is to draw attention to the ways in which wider shifts and processes are being experienced and made. Global shifts such as neoliberal strategies of managing finance and changing forms of sovereignty and governance do not simply create homogeneity the world over. They are shaped through individual and local projects that come to critique them, creating forms of experimentation and change. It is clear that to understand these features we need a richer characterisation of capitalist markets and the businesses within them (see Jacobs and Mazzucato 2016, 18) to look at what the economy is, beyond ideas about exchange and formal neoclassical ideas of maximising individuals.