Joseph G. Rayback - History of American Labor

Here you can read online Joseph G. Rayback - History of American Labor full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Free Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:History of American Labor

- Author:

- Publisher:Free Press

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

History of American Labor: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "History of American Labor" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A compact and comprehensive chronicle of where labor has been and where it is today.

History of American Labor — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "History of American Labor" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 1959, 1966 by Joseph G. Rayback

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

THE FREE PRESS

A Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc.

866 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10022

www.simonspeakers.com

Collier Macmillan Canada, Ltd.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 59-5344

Printed in the United States of America

printing number

ISBN: 978-0-0292-5850-7

ISBN: 978-1-4391-1899-3

to Kay Who assisted in the preparation of four versions of this book

In preparing the original edition of this book, published by The Macmillan Company in 1959, I had several goals in mind. I wanted to write a history of American labor in which labor was regarded not as a separate entity but as an integral part of American life. Accordingly, and within the limits set by available space, I tried to present the growth of labor against the background of American political, economic, industrial, and social history. Second, I tried to correct the all too common impression that labor as it is known today somehow appeared out of the factory system in some vague period after the Civil War. I therefore gave more than usual attention to earlier developments: the colonial labor systems, the role of labor in the American Revolution, the early labor associations, and the pre-Civil War developments upon which most latter-day labor institutions and traditions and thinking were based. Finally, I tried to indicate the effect of labor upon American institutions. For that reason, without neglecting labors relationship to employersin which relationship labor often made economic gainsI also gave more than usual attention to labors roles in politics and in the legislative process, through which its influence upon American institutions was most often felt.

In this revised edition, my goals have remained the same. Aside from correcting some errors to which my friends and my reviewers have called my attention, I have had one other fundamental aim: I have tried to bring the history of American labor up to date. The original edition ended with the expulsion of the teamsters from the A.F.L.-C.I.O. at the end of 1957; this edition continues the history to the middle of 1965, when much of the political program that labor had developed since the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act was finally being enacted and when an expansive economy appeared to presage a favorable reversal in labors slowly declining fortunes.

I have not revised the bibliography; instead I have attached an addendum of significant books and articles published since my last writing. I have, however, totally revised the index.

JOSEPH G. RAYBACK

A History of American Labor

The Colonial and Revolutionary Era

The Colonial Economy

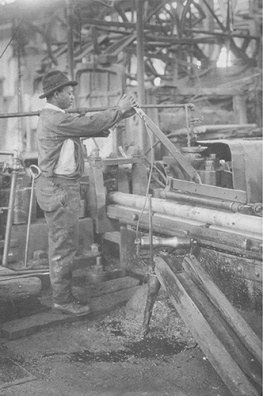

Like all pioneer societies the American colonies had an agricultural economy. But while the overwhelming majority of inhabitants in every colony earned their livelihood either as farm owners, tenants, or hired hands, the colonial economy was not exclusively agrarian. From earliest days farmers hired workers to build houses, bedsteads, and to make shoes and other products. The farmer supplied the raw materials to be transformed into finished products; the workers supplied the tools. Under such circumstances the farmers household became a manufactory and the hired men became the first industrial laborers. These laborers were itinerant, moving from farmhouse to farmhouse with their tools and skills; securing lodgings, board, and wages; and departing when the needs of the farmer-employer were satisfied. The itinerant laborer never disappeared from the colonial scene. Throughout the era, farmers continued to hire farm hands and wandering mechanicks whenever needs demanded. Even in the nineteenth century the itinerant worker was a common sight in sparsely settled frontier areas.

Itinerant manufacturing did not long dominate the colonial industrial scene. As population increased and thickened, the nonagricultural laborer who had accumulated a little capital settled down in town, erected a home, and opened a workshop. At this point industry entered the custom-order stage. A one-man industry, it depended largely at first on individual orders from merchants and farmers who could supply the materials to be transformed. Later, the workshop owner himself began to supply the raw materials of his trade which were transformed at the customers bidding.

While custom-order industry remained widespread throughout most of the colonial era, it gradually gave way to another form of enterprise. The change was occasioned primarily by the transformation of towns into cities and by the growth of a large population within the city environs. As the market expanded, the workshop owner began to employ journeymen to increase production; simultaneously he began to stock up on finished products made by his journeymen for sale to sojourners and visitors. Two classes of product were developed: a superior quality for the custom-trade and an inferior quality known as shop work for the lower-level trade. The new stage, known as retail-order industry, appeared as early as 1715 and reached a climax in the last twenty years of the century.

The change produced Americas first industrial classes. In earlier stages there were no distinct employer-employee elements; in the retail-order stage the workshop owner became an employer-merchant. He ceased, except on occasion, to perform manual labor and secured remuneration mainly from his managerial ability and his investments. Relations between him and his journeymen were harmonious. The workshop master was still a skilled worker intimately acquainted with his journeymens psychology. Moreover, the market was still local: the existing turnpikes were primarily feeders from the city to the near countryside. Since the market was restricted and all masters were confronted with similar conditions, it was simple to equalize competition and to satisfy journeymens wage demands by shifting any increase in wages to consumers. Journeymen, in turn, recognizing that their wages could best be maintained by cooperating with the masters in suppressing price-cutting competitors, actively supported their employers against those masters who refused to abide by established standards. Evidence of this harmony of interest was revealed by the establishment of mechanics societies during the eighteenth century.

Throughout these developments, manufacturing remained essentially a handicraft enterprise. A considerable portion of it was always conducted, with or without the supervision of an itinerant laborer, in the household, and some was carried on in plantation workshops. But most manufacturing occurred in or near towns and cities. In these the typical workshop of the retail-order stage employed one or two journeymen and an equal number of apprentices. Some shops were largernotably in the carpentry and cabinet trades, in weaving, and in the tanning and shoe industries. Saw, grist, and flour mills, in which water or wind power supplemented handicraft labor, employed from two to five men. Distilleries, breweries, paper and gunpowder manufacturies, shipyards, and ropewalks achieved greater size, employing generally from five to ten, and sometimes as many as twenty-five laborers. The giant of colonial manufacturing enterprise was the iron industry, established in rural areas where there was an adequate supply of ore, water power, and large quantities of wood to be used for charcoal. An iron plantation averaged twenty-five employees; a number in every colony had more than one hundred workmen.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «History of American Labor»

Look at similar books to History of American Labor. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book History of American Labor and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.