Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

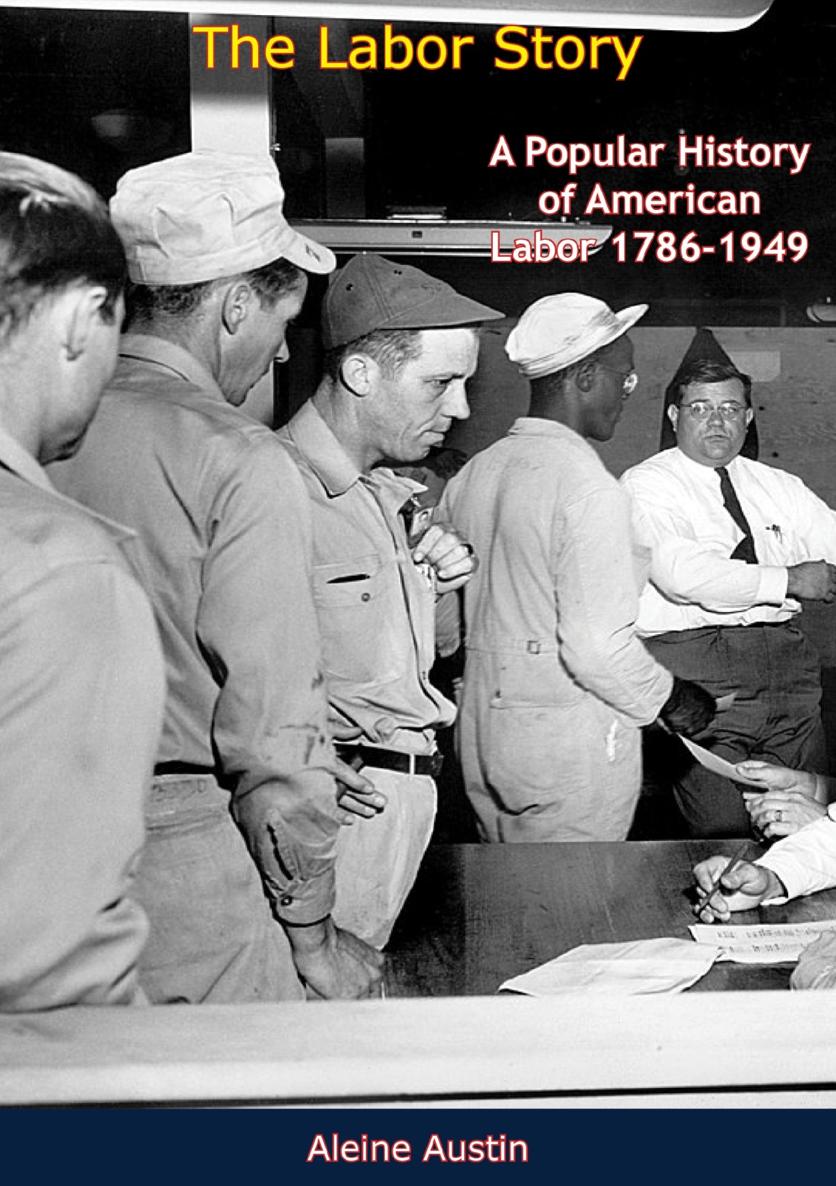

THE LABOR STORY

A POPULAR HISTORY OF AMERICAN LABOR

17861949

BY

ALEINE AUSTIN

PREFACE

THE story of America is the story of its people. It is the story of the daily lives of men and women seeking to fulfill their needs and hopes and ideals. For, as Carl Sandburg has said:

The people hold to the humdrum bidding

of work and food

while reaching out when it comes their

way

for lights beyond the prison of the

five senses

for keepsakes lasting beyond any hunger

or death.

This reaching is alive.

The story of this reaching, this striving of the common man, is unknown to most of us. It is rarely mentioned in our history books. They tell us of the heroic deeds of our statesmen and politicians, our military leaders and industrialists. That is one part of our American heritage. The labor story is another.

From the time this country began, workingmen have fought and starved and often died to better the life of the common man. The struggles of one generation have been carried on by the next. Where one group has failedthe next group has won. Gradually improvements have been granted. Gradually democracy has been strengthened.

Today we enjoy the fruits of this constant struggle for human dignity. Every American child is entitled to a free public education. Citizens need not own property to vote or run for office. Most public officials are elected directly by the people. No one can be thrown into jail because he is unable to pay a debt.

Child labor is illegal. Eight hours is the standard work day. Employers must pay workers a minimum wage. Safety laws must be observed. Many workers are insured against accidents on the job. Workers out of jobs receive unemployment compensation. The aged are entitled to old-age insurance. Employers may not fire workers for union activities.

These conditions did not fall into our laps automatically. They were fought for. They were fought for by generations of workers who joined together in trade unions to win a better life for themselves and their children. The story of their struggles is a dramatic onean inspiring one. It is one that all Americans should know and take pride in. The following pages tell that story.

CHAPTER ITINKER, TAILOR, SHOEMAKER, SAILOR

IN 1806, eight shoemakers stood in a Philadelphia courtroom awaiting the verdict of the jury in the now famous Cordwainers Case. Their trial had been a dramatic onea controversial one. Several months earlier, their employer had brought them to court as lawbreakers. Their crime? They had formed a union and had struck for higher wages.

The court upheld the position of the employerit found the shoemakers guilty . Of what? Of criminal conspiracyof joining together in a union and forming a combination and conspiracy to raise wages. An individual employee could legally ask his employer for a wage increase, the court hastened to assure the cordwainers. Nothing illegal about that (and, of course, nothing very effective about it either). But for workers to form a union, for workers to agree to stick together and refuse to work for low wagesthat was a conspiracy. That was illegal in the United States of America in 1806.

And still, workers formed unions. Laws and courts and employers opposition could not stop them. Unions were their only protection against changing conditions that were worsening the lot of the skilled handicraftsmen and depriving them of the independence they had known in the colonial period and during the early years of the Republic.

In those days, a shoemaker, for instance, often worked for himself in his own home as an artisan shopkeeper. He owned his toolshis awl, last, scissors, rasp, bench, and the like. He owned his raw materialhis leather, thread, beeswax, and even the iron and wood from which he made the nails for the townsmens shoes. He was an independent worker, who depended on no one else for a job. Nor did he receive just a meager wage for his work. Because he owned his own equipment, because he worked for himself, he received the full amount his work was worththe full price paid by the customer.

Later, as the demand for goods grew, the artisan shopkeeper, or master craftsman as he was then called, took on one or two apprentices and journeymen as assistants. Most apprentices were young boys who received intensive training from the master over a period of years. They then became journeymen, receiving still further training and experience, until eventually they were equipped to set up their own shops and become masters themselves.

In those days, the early and middle 1700s, the master and his assistants made products only for the home market, for the people in their own town. If someone in Philadelphia needed shoes, he would order them from one of the local shoemakers. Then the master, or one of his assistants, would make that pair of shoes. He would do the whole job. There was no such thing as one person making the soles, another doing the stitching, and another cutting the leather. This was how all goods were produced at that timenot only shoes, but clothes, hats, furniture, and all other commodities people needed. The workers of the time, the carpenters, masons, smiths, shoemakers, and tailors were all skilled workers.

The life of the handicraft worker was a comparatively satisfying one. Most craftsmen owned their own small homes and a little plot of land. When things were slack in the shop, they were able to turn to farming to sustain themselves. Unemployment did not leave them desperate and penniless. They were independent, resourceful people; they had pride, self-respect, and security.

The journeymen in the shop performed their work in an atmosphere of comparative freedom. A historian of the period observed that when a mechanic left his work at night he might be expected back in the morning, but there were no special grounds for this expectation. He might drop in the next morning or next week. Often, the men in the shop hired a boy to read to them while they worked. They were regarded as intelligent and thoughtful peopleas social equals of the master who owned the shop.

Although their wages were low and their hours long, the journeymen considered their interests to be much the same as the master craftsmans. They worked beside him in the shop, they ate with him, they lived much the same kind of life, and eventually they themselves became masters. For these reasons, the relationship between the masters and the journeymen who worked for them was a friendly one. They even belonged to the same benefit societies formed to assist each other in case of accident, illness, or death.