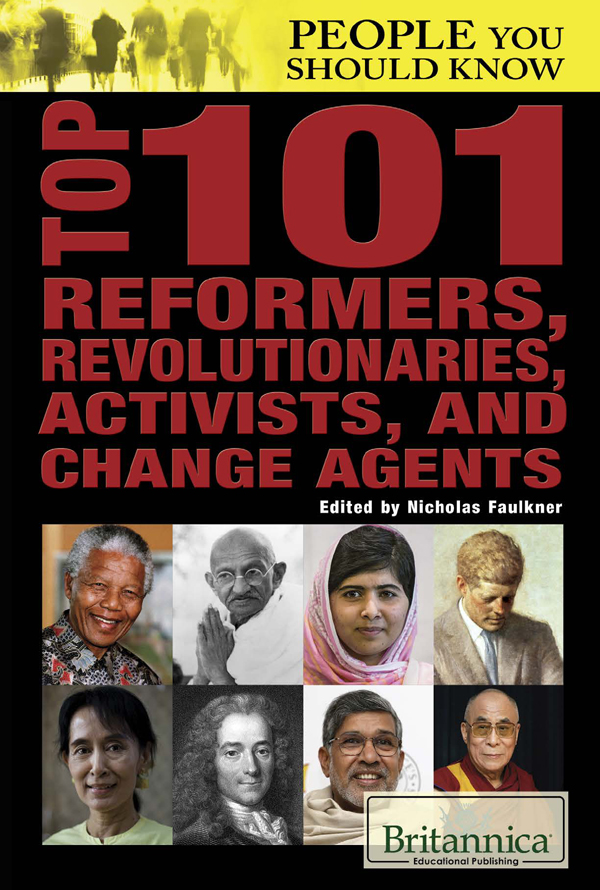

Published in 2017 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2017 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2017 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering:Executive Director, Core Editorial

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Nicholas Faulkner: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Michael Moy: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Sherri Jackson: Photo Researcher

Introduction and supplementary material by Nicki Peter Petrikowski

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Faulkner, Nicholas, editor.

Title: Top 101 reformers, revolutionaries, activists, and change agents / edited by Nicholas Faulkner.

Description: First edition. | New York : Britannica Educational Publishing in association with Rosen Educational Services, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050940 | ISBN 9781680484977 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Social reformers--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Political activists--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Revolutionaries--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Social change--History--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HN8 .T67 2017 | DDC 303.48/4092--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2015050940

Cover (top left), Andreas Rentz/Getty Images News/Getty Images ; cover and interior pages border iStockphoto.com/urbancow

CONTENTS

O ne of the great strengths of the human race is the ability to change. Over the course of history, people have adapted to vastly different circumstances, and they have changed their environments to better suit their needs. Change does not only occur as a reaction to outside factors, though. Human society is bound to change as well. Sometimes this change begins with just one person, one creative thinker showing that things can be done better than they were done before, or one brave soul standing up against what they believe to be wrong.

For statesmen and politicians, changing the status quo is part of their job, and enacting reforms that improve the life of those they govern is one of the things they are measured by and remembered for, as Abraham Lincoln is for abolishing slavery in the United States.

The pursuit of freedom can lead to revolutions like the ones connected with Thomas Jefferson and Smon Bolvar, but not every revolutionary is as successful; Che Guevaras guerrilla war for a socialist world failed.

Spiritual leaders such as the Dalai Lama, Pope John Paul II, and Pope Francis have shown an influence that goes beyond their religious groups and enters the realm of politics, and Martin Luthers endeavor to reform the medieval Roman Catholic Church resulted in unforeseen political upheaval.

One does not have to be in a position of power to cause change, though. With a single act of defiance against social injustice a person can become a symbol, such as Rosa Parks was for the United States civil rights movement, and sometimes the most unlikely person, such as Joan of Arc, born a simple peasant girl, can change the fate of nations.

Change is often established by force of arms as military leaders such as the Scottish national hero William Wallace or George Washington show, but violence is not always the way. The nonviolent resistance practiced by Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., has also proved to be effective, and social work can have a positive effect on many lives, as the examples of Jane Addams and Mother Teresa illustrate. Scientists such as Galileo Galilei and Charles Darwin have influenced how we see the world through their discoveries, opening up new ways of thinking, and innovators have changed the way the world works with their inventions. Without Johannes Gutenberg, for example, this book would possibly not even exist, and neither would the books Upton Sinclair wrote to fight for social justice.

Whether it is brought about by reforms pushed through by powerful politicians or fought for by activists, whether it is established through armed force or nonviolently, change can take many forms, and many deplorable situations have already been changed for the better thanks to the efforts of some of the most remarkable people in history.

(b. 1860d. 1935)

A n early concern for the living conditions of 19th-century factory workers led American reformer Jane Addams to assume a pioneering role in the field of social work. She brought cultural and day-care programs to the poor, sought justice for immigrants and blacks, championed labor reform, supported womens suffrage, and helped to train other social workers. Addams was cowinner (with Nicholas Murray Butler) of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

Jane Addams was born on September 6, 1860, in Cedarville, Illinois. Her father, John Huy Addams, was a wealthy miller, a state senator, and a friend of Abraham Lincoln. Jane was the youngest of five children. She graduated from Rockford Female Seminary in Illinois in 1881 and was granted a degree the following year when the institution became Rockford College. Following the death of her father in 1881, her own health problems, and an unhappy year at the Womans Medical College in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Jane Addams was an invalid for two years. She subsequently traveled in Europe in 188385 and stayed in Baltimore, Maryland, in 188587.

In 188788 Addams returned to Europe with a Rockford classmate, Ellen Gates Starr. During this trip they visited Toynbee Hallthe worlds first social settlementin London, England. Upon returning to the United States, Addams and Starr decided to create something like Toynbee Hall. They settled in a working-class immigrant district in Chicago, Illinois. There they acquired a large vacant residence built by Charles Hull in 1856, and, calling it Hull House, they moved into it on September 18, 1889. Eventually the settlement included 13 buildings and a playground as well as a camp near Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Many prominent social workers and reformersincluding Julia Lathrop, Florence Kelley, and Grace Abbottcame to live at Hull House, as did others who continued to make their living in business or the arts while helping Addams in social settlement activities.

Among the facilities at Hull House were a day nursery, a gymnasium, a community kitchen, and a boarding club for working girls. Hull House offered college-level courses in various subjects; furnished training in art, music, and crafts such as bookbinding; and sponsored one of the earliest little-theater groups, the Hull House Players. In addition to making available services and cultural opportunities for the largely immigrant population of the neighborhood, Hull House afforded an opportunity for young social workers to acquire training.

Outside of her Hull House work, Addams and other reformers helped to establish the worlds first juvenile court, tenement-house regulation, an eight-hour working day for women, factory inspection, and workers compensation. In addition, Addams strove for justice for immigrants and blacks and advocated research aimed at determining the causes of poverty and crime. In 1910 she became the first woman president of the National Conference of Social Work, and in 1912 she played an active part in the Progressive Partys U.S. presidential campaign for Theodore Roosevelt. At The Hague (Netherlands) in 1915 Addams served as chairman of the International Congress of Women, following which was established the Womens International League for Peace and Freedom. She was also involved in the founding of the American Civil Liberties Union in 1920. In 1931 she was a cowinner of the Nobel Prize for Peace.