Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Miriam Sicherman

All rights reserved

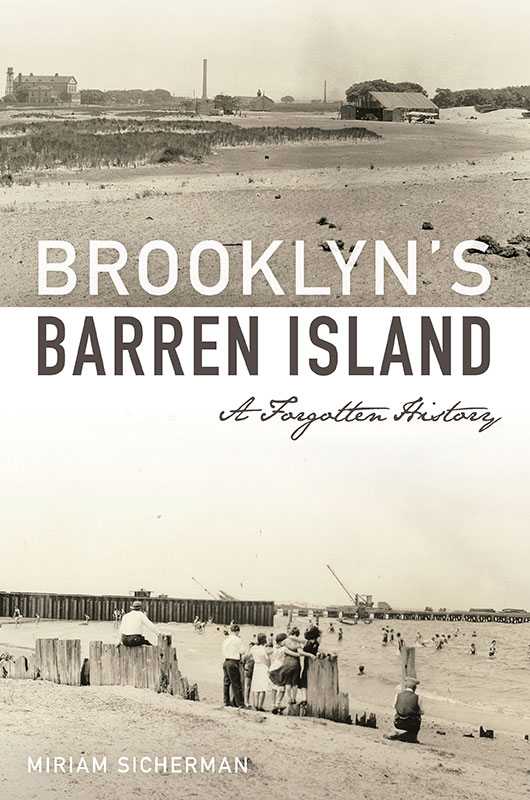

Front cover, top: Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Archives, Eugene L. Armbruster Photographs; bottom: Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Archives, Eugene L. Armbruster Photographs.

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.856.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019948155

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.431.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

To the memory of Jane F. Shaw (18671939), educator and advocate, and to the past, present and future of Una Yoorim Sicherman Rose.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people helped me gather and understand resources for this project. I would like to thank National Park ranger J. Lincoln Hallowell for providing the invaluable oral history of William Maier, as well as Mickey Maxwell Cohen and Gunda Narang for providing Josephine Smizaskis oral history. These resources made a huge difference in my ability to understand Barren Island from the point of view of Barren Islanders. Many others also responded to my questions and requests for resources, often going above and beyond in their efforts to help, including Wade Catts, Felice Ciccione, Mike Cinquino, Joseph Coen, Peggy Gavan, Jim Harmon, Dan Hendrick, Melanie Kiechle, Max Liboiron, Dana Linck, David Ment, Robin Nagle, Jozef Malinowski, Brian Merlis, Kevin Olsen, Amanda Patenaude, David Naguib Pellow, Skip Rohde, Elizabeth Royte, Lee A. Rosenzweig, Adam Schwartz, Lori Sitzabee, Howard Warren, Mary Willis, Ingrid Wuebber, Don Zablosky and Carol Zoref. They provided tremendously helpful, hard-to-find materials and advice.

Librarians and archivists at Brooklyn College, the Brooklyn Historical Society, the Brooklyn Public Library, the New York City Municipal Archives, the New York State Archives, Queens Public Library and the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, as well as park rangers at Floyd Bennett Field, helped me find and understand many important resources as well.

My masters thesis advisor at Brooklyn College, Professor Michael Rawson, encouraged me to pursue this topic in spite of the challenges of finding information. Im very grateful for the guidance and feedback he provided at each step of the research and writing process, and for his suggestion that I consider publication.

And to the many friends and family members who either enjoyed or endured my long tales of Barren Island, and even accompanied me on field trips to its vanished shores, thank you!

INTRODUCTION

One day in early March 1909, a New York City health inspector got on a boat at Canarsie Pier in Brooklyn and sailed to a place in that borough called Barren Island. In response to complaints from unspecified persons, he had come to find out who owned the more than five hundred illicit hogs that roamed freely amid the sand, marsh plants and garbage. (It was legal to keep hogs in a pen but not to let them roam.) All of the islanders disclaimed any knowledge of the hogs, and, presumably, they assumed that was the end of the matter.

But it was not. The twelve policemen of the health squad arrived by powerboat at 9:00 a.m. on Tuesday, March 16, 1909, a few days after the inspectors visit, revealing not a hint of their purpose. These strapping men were armed to the teeth, the New York Times reported on the following day, with revolvers and two hundred rounds of ammunition apiece. Led by city sanitary superintendent Walter Bensel, they had a singular mission: Kill all the unpenned hogs on Barren Island. They would need all the strength they had to accomplish their assignment.

Soon after they disembarked, their quarry began to appear all around them. A shot rang out and a big white hog rolled over on his back.From that moment action was fast and furious. As the police dispersed across the island, they quickly discovered that their task would not be easy. First of all, the enormous creatures often had to be shot multiple times before they would fall dead. More dauntingly, seemingly the entire female population of the island suddenly emerged from their homes to protect the very same hogs whom theyd claimed no knowledge of just days before. The women, few of whom could speak English, were crying and pleading with the policemen not to shoot the hogs, while between their sobs they called what sound like Toi, Toi, Toi, trying to get the rooters out of danger.

Immune to this pleading, the brawny health police proceeded with their grim assignment. They strode across the sandy, roadless island, shooting every hog they could findhogs of every description. Some were so old and lazy they would hardly get out of the way when kicked, while others, long legged, skinny and shaggy as Shetland ponies, could give a deer the race of his life in a Marathon. Although Barren Islands women presented the first line of defense, a number of men came from the factories to rescue their hogs, several picking up in their arms porkers which could not have weighed less than 150 pounds each, carrying them bodily into the houses through the front doors. In addition to the lucky hogs whose owners herded them into their homes, some others escaped into the nearby marshes.

Several hours later, there were no more live hogs to be found outdoors. The policemen packed up their guns and headed back to the boat. Meanwhile, those of the natives who were not engaged in dragging in the dead hogs preparatory to a great fry and roast last night were at their gates, shaking warning fingers and menacing fists at the policemens broad backs.

This event, though it was a one-time incident, exemplifies many features of the unusual community on Barren Island in Jamaica Bay, where from the 1850s through 1936, several thousand immigrants and African Americans made a living from a variety of nuisance industries. Though the health policemens boat ride took only thirty minutes, it was quite common for the trip to take hours or even for it to be impossible, creating conditions where an isolated and neglected community developed its own quite effective survival strategies. The population over the years ranged from a couple of hundred to around eighteen hundred mostly disenfranchised residents, its small size allowing its municipal overseers to ignore it with few repercussions. The islanders responded creatively. They took advantage of their virtual invisibility in many ways, in this case by openly keeping hundreds of free-roaming hogs, contrary to the laws of the city. These hogs were a constructive response to two facts: garbage, which hogs ate, was everywhere on the island; and poor transportation made fresh meat hard to get. After the policemen came to shoot the hogs, the islanders made the best of that, too: if you cant save your hogs, you might as well have them for dinner. The hog situation was also indicative of ways in which islanders existed in a sort of living past. It had been nearly fifty years since free-roaming hogs had been eradicated from more urban parts of the city, But the islanders quietly went on with their lives, coming up with countless ways to both benefit from, and compensate for, their geographical isolation and the neglect with which they were treated by the authorities. Ultimately, they organically created a unique community at once urban and rural, old fashioned and cutting edge.