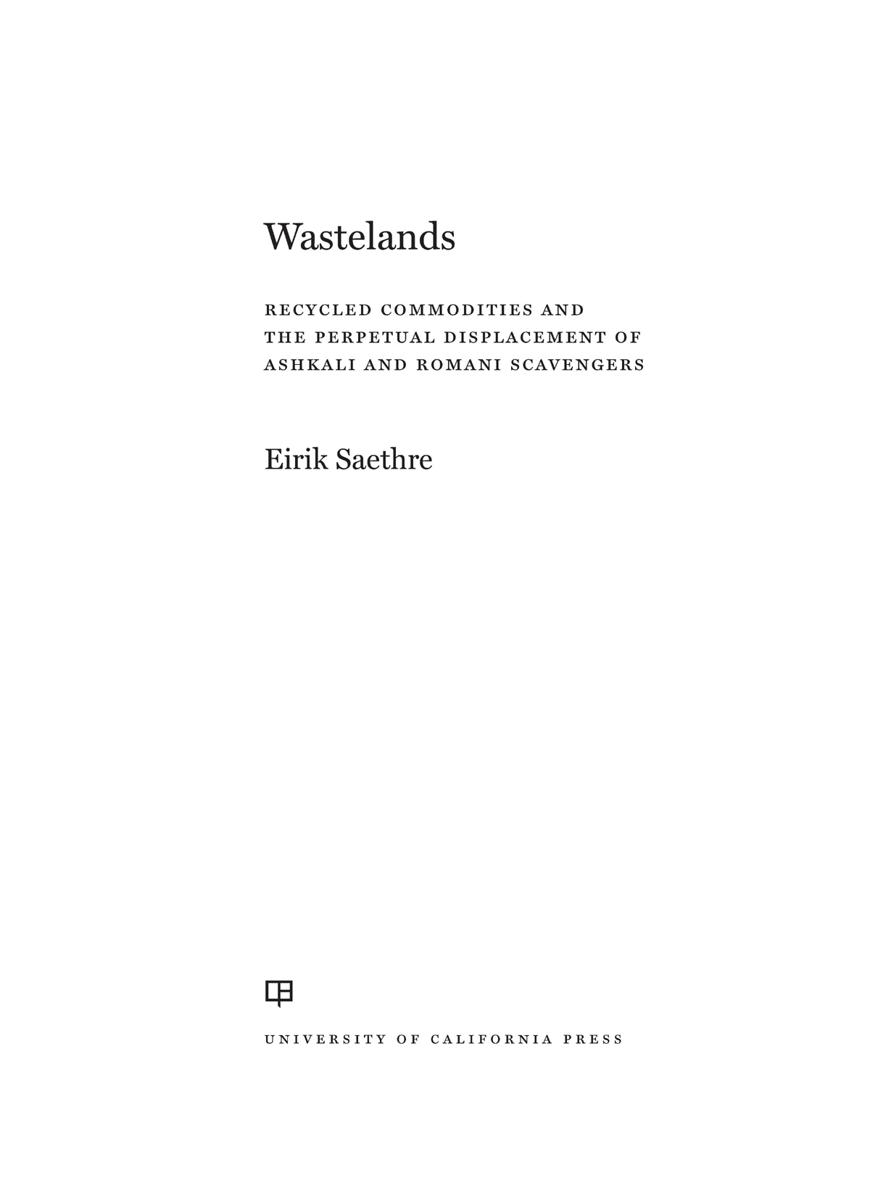

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2020 by Eirik Saethre

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Saethre, Eirik, author.

Title: Wastelands : recycled commodities and the perpetual displacement of Ashkali and Romani Scavengers / Eirik Saethre.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020017886 (print) | LCCN 2020017887 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520368491 (hardback) | ISBN 9780520368514 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520976139 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : RomaniesSerbiaHistory. | RefugeesSerbiaBelgrade. | Dumpster divingSerbiaBelgrade.

Classification: LCC DX 269 . S 24 2020 (print) | LCC DX 269 (ebook) | DDCE 305.8914/9704971dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017886

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020017887

Manufactured in the United States of America

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

Foremost, I am an extremely grateful for the overwhelming help and patience of Poljes Ashkali and Romani residents. They invited me into their homes, taught a very awkward American how to scavenge, trusted me with their stories, and never stopped looking after me.

I must also thank those individuals who generously supported me and my research in Belgrade. Slobodan Stankovi worked tirelessly as my research assistant. His remarkable insights, feedback, and linguistic skills played an enormous role in the success of this project. I could not have done it without him. I must credit Goran evo, my longtime friend and fellow Australian National University alum, for first encouraging me to work in Belgrade. Later, he supplied invaluable advice and logistical help, which made this research possible. Bojan iki coordinated my time in the Department of Ethnology and Anthropology at the University of Belgrade and commented on an early draft of this book. Our discussions of Serbia and Serbian anthropology grounded my thinking and writing. Biljana Sikimi kindly shared her expertise regarding Serbias diverse Romani population and introduced me to academic networks in Belgrade. Finally, I must acknowledge the financial assistance of the Fulbright Scholar Program and the support of the United States Embassy in Serbia.

I also received tremendous help from my friends and colleagues in the United States. From the very beginning, Ruth Anderson contributed her boundless encouragement, knowledge, and editing skills. Ian Hancock graciously provided advice prior to my departure for Belgrade and then upon my return. I would also like to thank Carol Silverman and Melissa Caldwell, who offered insightful and valuable comments on the manuscript. At the University of Hawaii at Mnoa, I am grateful for the unceasing support and guidance of Christine Beaule, Jan Brunson, Alexander Mawyer, and Christian Peterson.

Introduction

THE OTHER WORLD

Polje was a space unto itself. An informal Romani settlement on the edge of Belgrade, it was home to approximately two hundred Ashkali and Roma living in small one-room shacks. Piles of trash lined the narrow lane that served as the main thoroughfare. Water was obtained from nearby fire hydrants while electricity was siphoned from streetlights. Completely concealed by a series of small berms, Polje was situated between two contrasting geographies. On one side, gray concrete high-rise buildings punctuated an urban landscape, and on the other, bucolic green fields stretched to the horizon. If Polje seemed out of place, so too did its inhabitants. Every resident was a migrant, refugee, or displaced person. A site of temporary asylum, the settlement was largely divorced from the realm beyond its borders. A teenage resident, Deon, aptly described Polje as the other world. But the settlement was also an Other world, where the exiled sought to build their lives before they were inevitably dislodged once more.

Characterized as unhygienic, a squatter camp, and a slum, Polje was one of an estimated 583 substandard Romani settlements that pervaded Serbia.Romani settlements were socially, materially, economically, and legally isolated from the rest of the nation. The most substantive link between Poljes inhabitants and the world outside its borders was the trash. In the urban sprawl just beyond the settlement lay a realm of discarded commodities that could be converted into food, housing, and cash. In so doing, Ashkali and Roma sought to turn garbage into success. Like everyone else in Polje, this is what drew Bekim to the settlement.

Although he was twenty-four years old, Bekim stood just over five feet tall and weighed barely ninety pounds, a result of being malnourished for most of his life. Given his slight build, Bekim had difficulty finding clothes that fit. Because he refused to wear boys sizes, he was constantly pulling up his pants in an effort to keep them from falling off. But this did not bother Bekim, who often joked about his wardrobe malfunctions. However, his humor belied a history of loss and dislocation. He came to Serbia as a child when his family fled the Kosovo War. Arriving in Belgrade, they first lived in Zgrade, and then, after it was destroyed by the Serbian government, Polje. Despite residing in Serbia for almost two decades, Bekim still lacked identity documents. As a result he was unable to work legally, open a bank account, or access state health care. Barred from the formal economy, Bekim earned money recycling paper and metal he found in dumpsters. This work was filthy, physically debilitating, and barely provided enough income to support his family. Married at sixteen, Bekim had fathered eight children, four of whom died in infancy. His wife, Fatime, was pregnant again and he fervently hoped this child would live.

Late one night as Bekim and I visited a nearby supermarket for food, his incessant struggle for survival was vividly illustrated. Walking out of the settlement, we entered a busy street lined with bright lights and tall buildings. As Bekim contemplated the proliferation of stores along our route, he asked if I had visited the nearby mall. He had never been inside and was curious what it was like. Even though it was not far from his home, the mall was a place Bekim would probably never go. People like him, he said, could get into trouble if they went to malls. Bekim knew the areas he should avoid. Suddenly, his stomach started to rumble. There had not been much food for dinner and Bekim only ate a fraction of it, wanting to ensure that his children had enough. Thinking about his last meal, Bekim casually commented that another one of his molars had fallen out. This was the second in as many weeks and a little more than half of his teeth remained. Stoically, Bekim added that at least it had been painless. He expected to begin losing his incisors soon, which were already black with decay.

Before long, we crossed an empty parking lot and arrived at the front of a large supermarket. Its windows were dark and the building appeared deserted. As I expected, it had closed an hour earlier. We had not come to shop. Wanting to avoid harassment, Poljes residents assiduously avoided purchasing food at supermarkets. Nevertheless, these large stores were an important source of sustenance for Bekims family. Skirting around the side of the building, we made our way to a row of dumpsters in the rear. With Bekim starting at one end and me at the other, we meticulously combed through their contents. This is where we hoped to obtain our next meal. We were searching for any rotten fruits and vegetables that the supermarket had discarded at closing. While Serbs expressed disgust at eating food found in dumpsters, it was an accepted part of everyday life in the Other world. Molding tomatoes were not trash; they were nourishment. But despite our efforts the dumpsters yielded nothing. Fortunately, two other supermarkets were not far away. Perhaps, Bekim mused, we would have better luck there.