Copyright 2016 by Kenneth E. Miller

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, chemical, optical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-936012-78-7 | eISBN: 978-1-936012-79-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948169

Publishers Cataloging-In-Publication Data (Prepared by The Donohue Group, Inc.)

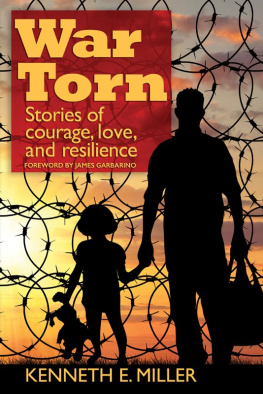

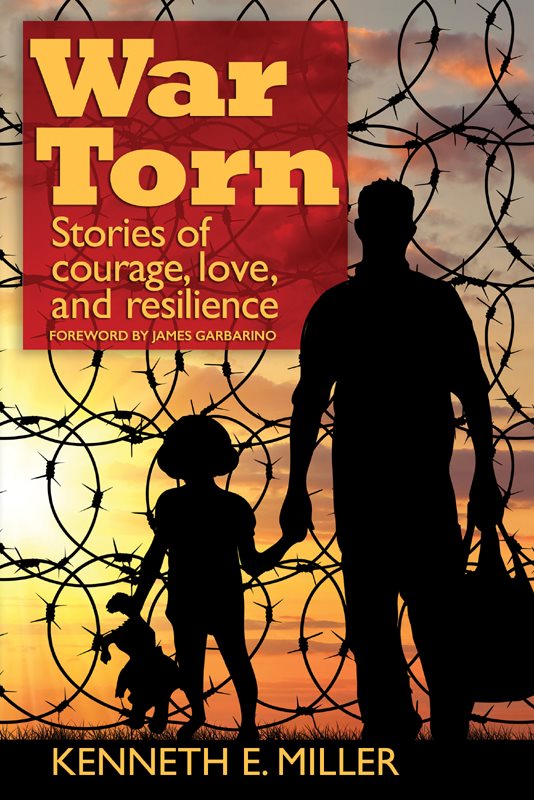

Names: Miller, Kenneth E. (Kenneth Eric), 1963- Title: War torn : stories of courage, love, and resilience / Kenneth E. Miller.

Description: Burdett, New York : Larson Publications, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016948169 | ISBN 978-1-936012-78-7 | ISBN 978-1-936012-79-4 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Miller, Kenneth E. (Kenneth Eric), 1963- | Genocide survivors. | Forced migration. | Refugees.

Classification: LCC HV6322.7 .M55 2016 (print) | LCC HV6322.7 (ebook) | DDC 364.15/1--dc23

Published by Larson Publications

4936 NYS Route 414

Burdett, New York 14818 USA

https://www.larsonpublications.com

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Permissions:

page 72: Mark Knopfler, Brothers in Arms, in Brothers in Arms , published by Chariscourt Ltd / Rondor Music (London) Ltd. Reprinted by permission.

page 219: The Other War: Iraq Veterans Speak Out on Shocking Accountsof Attacks on Iraqi Civilians. Reproduced by permission of DemocracyNow! (democracynow.org). See also p. 294, note 5.

DEDICATION

To all those courageous souls

Who survived the devastation and chaos of war

Invited me into their lives

Shared their stories

Spoke occasionally of nightmares

not dissolved by the morning sun

And amazed me with their laughter

I dedicate this book with profound gratitude

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

by James Garbarino, PhD

Loyola University Chicago

I MET Ken Miller more than twenty years ago, when he was just setting out on the intellectual and spiritual journey that has led him to write this bookstruggling to make sense of what he heard and saw in Guatemala and in refugee camps in Mexico. I am pleased to see what he has made of these more than two decades of walking this walk, and talking this talk, but particularly listening to the stories of people who have lived through war and genocide. In this book he brings to the reader an intimate account of what he has heard, and seen, and felt, and understood from doing so.

In evocative and powerful prose, Ken captures the remarkable human capacity for resilience in the face of great adversity. He also writes with compassion about the lasting damage that war has on the human heart and mind, when the limits of resilience have been surpassed. This itself is an important point. Resilience is not a simple trait that you either have or dont have. It is itself a story, a story of how ones individual and social resources match up to the threats, challenges, and trauma of the environment that surrounds that individual. No one has absolute resilience; each of us has a breaking point. War Torn teaches us that.

It all begins with the stories. As Ken writes in the Introduction, There is something profound about the seemingly simple act of sharing ones stories with others who listen without judgment, or doubt, or fear of the discomfort that difficult stories may evoke. We unburden ourselves as the truth of our experience is known and documented. In the process, it loses its destructive power. This is a book of remarkable stories, told by a gifted storyteller who has spent his professional life listening to peoplechildren and adultswho have survived the horrors of war.

Ken Miller is a psychologist/therapist, a researcher, and a filmmaker, and he uses all three perspectives to capture one of the most important human rights issues we face as a global people: The wounding and killing of civilians has become an essential ingredient in the conduct of war, a means of spreading terror and silencing opposition to those in power or fighting to attain it. Across a wide range of socio-cultural contexts Ken has been there to help document, understand, and heal the fundamental traumas that arise from this darker truth. His stories come from and take the reader to Guatemala, Mexico, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and Sri Lanka. I myself have been to many of these places (in part as the basis for the writing of my book No Place to Be a Child: Growing Up in a War Zone ) and can attest to the fact that Ken is a trustworthy reporter of the many ways that war affects the inner and outer lives of people who, through no fault of their own, are suddenly caught in its destructive power.

Although the settings vary, there are important themes that run through the book: that we are as resilient as we are fragile; that healing often occurs in the absence of professional healers; and that the impact of war is far more complex than has been imagined by Western psychiatry and its related disciplines. For example, violence against women and children within their own families escalates markedly in times of war, as men struggle with their trauma, grief, and rage. Yet family violence is seldom mentioned in studies of war and mental health, an invisible source of trauma overshadowed by the more visible violence inflicted by soldiers and other armed combatants.

Ken also offers a well-grounded skepticism about some conventional approaches coming from mainstream mental health research and practice. One prominent example is the narrow focus on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as an organizing framework for approaching those touched (and engulfed) by war. I share this skepticism, and wonder if a more respectful and accurate term might be Post Traumatic Stress Development . Such a shift in terminology would recognize better the fact that our focus should be on how people bring psychological, social, and cultural resources to bear on themselves and their communities after they have experienced the horrors of war.

What is more, we must always ask: What if there is no post at all, and the war becomes an ongoing fact of life? What then? Indeed, understanding the psychological and social challenges of chronic stress and adversity is one of the important challenges facing those who work to support the resilience and healing of war-affected communities. As it is, I might add based upon my own work over the last twenty years, for those who live with the ongoing trauma of urban war zones in parts of American cities like Chicago, where some of the same dynamics between soldiers and civilians operate.

Stories of war and survival require cultural, social and psychological context if they are to illuminate meaning in a systematic way, a way that can inform social policypeace makingand professional practicetrauma-informed intervention. In each country where he has worked, Ken has become a student of the culture, balancing his grounding in Western psychological science with a respect for diverse beliefs about the causes of sufferingfrom witchcraft to spirit possession and karma . His appreciation for Western approaches to psychological healing is always and everywhere balanced by an appreciation for the power of local healing rituals.

I applaud Ken Miller for listening so well, and in telling us what he has heard, for forcing us to confront our own demons, but also for seeing the angels of our better nature amidst the chaos and suffering of war zones. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall find peace, and in so doing shall also find love among the human ruins of war. That message is strong in Kens workor more properly in the work of those who have lived through war to tell the tales. I am glad Ken has been there to hear and appreciate and collect and make sense of those tales. War Torn is a tough book to read in many ways, but it is an essential journey for all of us. We owe it to the victims of war and to ourselves and fellow travelers on the human journey.