Table of Contents

For Solomon, whose name means peace

We the peoples of the United Nations

Determined

to save succeeding generations

from the scourge of war...

UN Charter, 1945

Prologue

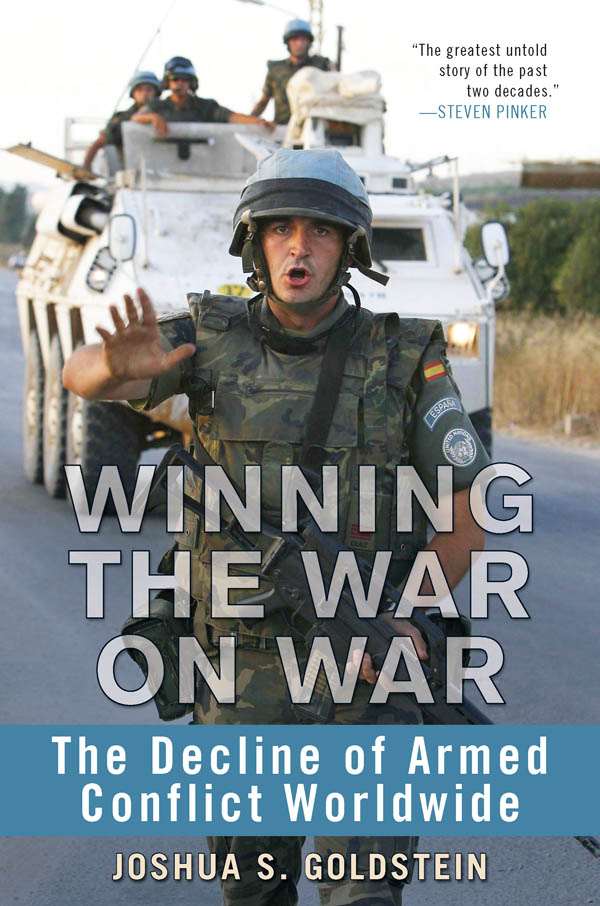

This book asks readers to break out of a dominant way of thinking about world affairs that focuses on negativity and drowns out progress. If we turn off the screech of alarmist news and overblown political rhetoric for a moment and look at hard evidence objectively, we find that many people in the world are working hard for peace, and in fact the world is becoming more peaceful. For this shocking idea to sink in requires either a paradigm shift or at least a broken TV set.

For those who are sure wars are getting worse all the time and that peace is an illusion, and will not believe any amount of evidence I produce to the contrary, I have one question: Compared to what? Take the situation in Iraq in 2011a terrible mess, Americans still getting killed by insurgents, civilians dying, the population unhappy, the government needing eight months to get organized after an election, the potential for civil war after the departure of U.S. forces. All true, and more, but compared to what? Compared to a few years ago when Sunni-Shiite sectarian violence ravaged the country? Compared to the period of the U.S. invasion in 2003, the looting, and the insurgency? Or compared to how Iraq would be if the United States had not botched the invasion? Or how it would be if fairies sprinkled magic dust over the country to end sectarian strife, corruption, and electricity shortages?

The ability to distinguish between bad (Iraq today) and worse (Iraq a few years ago) unlocks a profound understanding of todays world situation. The world is going from worse to bad, from the fire to the frying pan. Good newsunless you are freaked out by the frying pan and so upset by the bad coming at you constantly in the news that you cannot compare it with anything.

With the frying pan still pretty hot, it is easy to assume that war is getting worse, and can never get better, because everyone knows that war is inevitable. But if we look past the heat and smoke, a radical notion emerges in this book. War among human beings is not inevitable. Rather, the end of war, though also not inevitable, is possible. The possibility of an end to war is not something to be ridiculed, but to be pursued.

I hope that this story, one that tours some of the most awful war-torn places on earth but that is ultimately about peace, will inspire readers to seethrough the continuing fog of warour best qualities as human beings: our ability to communicate, to empathize, to cooperate, and to create a safer, freer, more prosperous world for our children.

WAR ON THE STREET OUTSIDE

Beirut, 1980

I have studied war as a professor for decades, but have been in a war zone only once. It was April 16, 1980, and I was driving into Beirut, Lebanon, from the airport with Black Panther founder Huey P. Newton and a half dozen of his friends to visit the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and meet its leader, Yasser Arafat. I was a white, Jewish, nonviolent twenty-seven-year-old who had met Huey just a few times but had worked on Black Panther community programs in the partys put down the gun phase in the early 1970s. The PLO was bringing in foreign big-shots to see its state-within-a-state in Beirut, and evidently did not know that the Black Panthers had fallen apart years ago and that Huey personally was on a cocaine-strewn path to self-destruction that would kill him within the decadeshot on the streets of Oakland.

When the PLO invited Huey to assemble a delegation for an expensespaid visit, he took his wife, brother-in-law, secretary, and a white supporter who was a friend of mine. I got myself invited along because there was extra space and I hoped to (and did) help Huey visit Israel afterward, as he had expressed a desire to do. We rode in from the Beirut airport and through the city in two cars, Hueys inner circle in the first and me with two other people in the second.

When I heard popping sounds ahead, I thought fireworks. After all, there was a lull in the civil war. Our airport arrival had been smooth (for one thing, the PLO seemed to bypass the Lebanese authorities altogether) and nobody mentioned trouble. True, the city was traumatized still from its recent years of civil war, and whole buildings gaped open from unrepaired shell damage. But there was a stable dividing line and cease-fire between the Muslim side, where we were, and the Christian side. If you stayed away from the dividing line and the Israeli border you were safeunless the crazy traffic killed you, but thats another story. So the popping sounds did not alarm me at first.

As we continued, though, the shots got louder and it became clear they were not fireworks but automatic weapons fire in the city streets. A gun battle was soon taking place a block ahead of us and our driver, completely calm, said, OK, somethings happening; well go another way, and turned the car around. He said, Dont worry, and I commented, I am worried. He remarked of the fighting, You get used to it, and I replied, I hope I never get used to it. I remember slouching down in the backseat of the car so that a stray bullet would have less chance to hit me if one came our way. But none did.

When we got to our hotel, Huey and his friends showed a certain amusement with the street fighting. Did you see that guy running along with the AK-47 nipping at his heels? they laughed. (Huey instructed us that as a civilian caught in a firefight you should walk away, since running makes you look like part of the actionadvice I thankfully have never had occasion to use.) I could not understand the drivers calmness and Hueys friends attitude about the fighting.

Up until then, for me, war was an absolute. Being in a war zone meant dying, and there was no connection in my mind between a war zone and daily life. But in Beirut I began to learn that war is relative, that most people in a war zone survive, that war is hell but also life goes on. In Beirut in 1980, if war took place a block away, you went on with your day. If war came onto your block, well, then you went inside.

That night, out the hotel window, I saw outgoing artillery fire from some blocks awaynot our block, though. A few minutes later incoming artillery set off big booms, but not close enough to break anything where we were. I realized that the incoming shells had landed pretty close to where the outgoing shells had come from. This made me feel safer because they seemed to know what they were shooting at and it was not me.

A five-year-old boy on his balcony was also not what the fighters were shooting at that day, but a stray bullet killed him. The days fighting had killed five people in all. I saw it in the next days newspaper. War took away this young childs life, with all the hopes and plans for the rest of it, and left a permanent gap in the fabric of his family and community.

For that five-year-old child, war was not relative; it was absolute. It does not matter whether he died among five that day or five thousand. It does not matter, for him, whether the street fighting in Beirut that day was a tiny fragment of a world awash in big wars, or the last skirmish on earth. (Similarly, the fact that deaths in Iraq hit a new low level in October 2008 did not matter for the family in Kirkuk that lost the last of its three sons, a seven-year-old killed by a stray grenade while playing soccer.)