This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

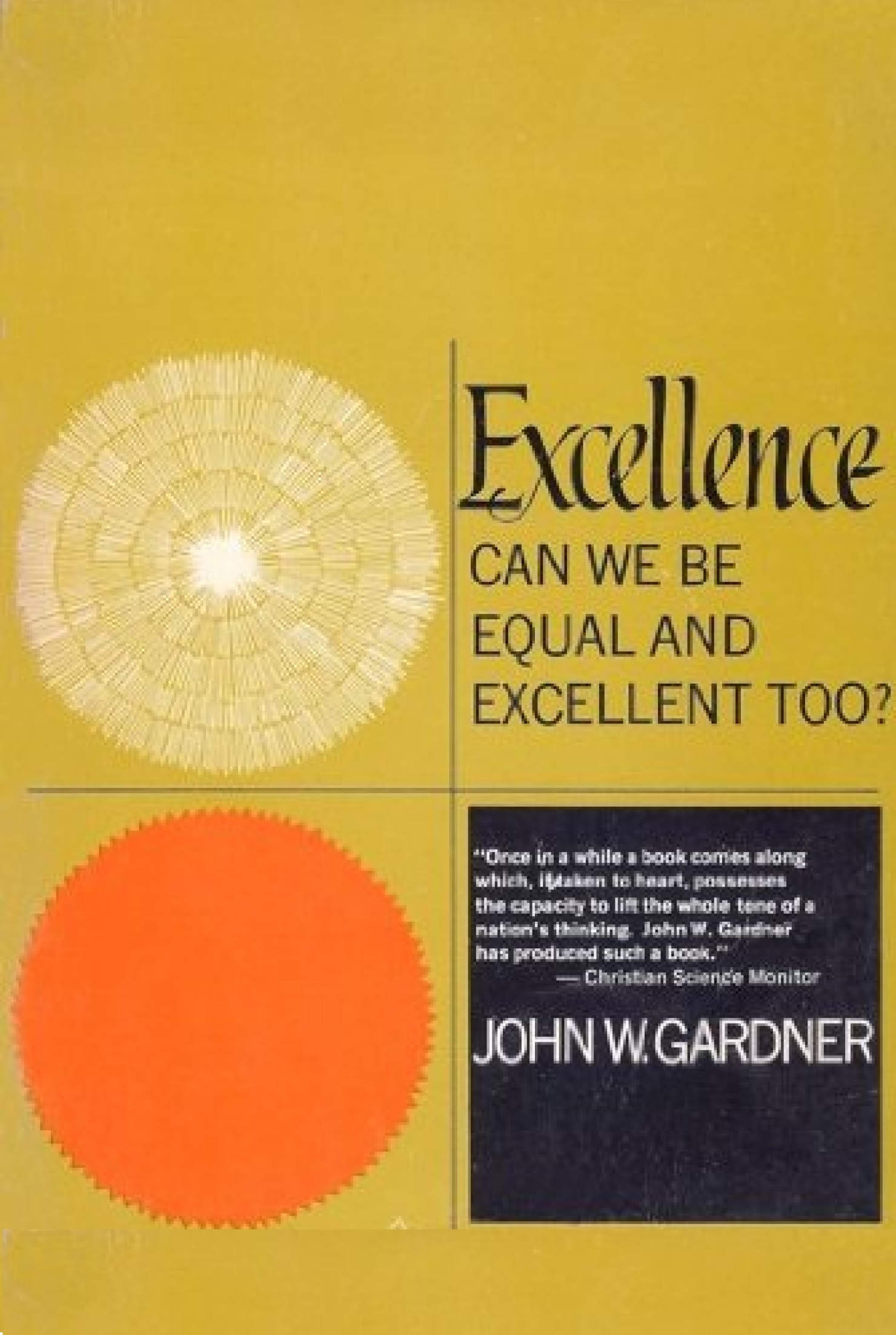

EXCELLENCE: CAN WE BE EQUAL AND EXCELLENT TOO?

BY

JOHN W. GARDNER

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

DEDICATION

TO MY MOTHER AND BROTHER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Jean Grolier, the great French book collector, placed inscriptions on the bindings of some of his books which indicated that the volumes belonged to Io. Grolier et amicorum (J. Grolier and his friends). This book should bear a comparable inscriptionnot on the binding but on the title page. Most authors incur obligations, but I feel that my debt is heavier than most.

First of all I must thank my generous and steadfast colleagues in Carnegie Corporation. Some of them read and commented on the first draft of the book; all of them put up with the heavy drain on my time and energies which authorship entails. I am particularly grateful to James A. Perkins, Florence Anderson, Frederick H. Jackson, Margaret E. Mahoney, Helen Rowan, John C. Honey, Lloyd N. Morrisett and Rosalinde B. Kaufman. Isabelle C. Neilson, whose devotion to excellence has been lifelong, assisted me at every stage of the book. The intelligent help of Helen C. Allan and the extremely competent assistance of Lonnie A. Sharpe were also deeply appreciated.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to those friends who took time from their busy schedules to read the manuscript and to give me the discerning guidance every author needs: Thomas R. Carskadon, Paul R. Farnsworth, Charles Frankel, Harold N. Graves, Caryl P. Haskins, Mrs. Marquis James, John M. Stalnaker, John D. Wilson and Dael Wolfle.

A special note of thanks is due to Lawrence A. Cremin and Julian P. Boyd, who supplied me with interesting and useful source material on certain of the subjects in the book.

Finally, the debt one never manages to acknowledge fullythe debt to ones family. My wife helped with suggestions at every stage. Both of my daughters, Stephanie and Francesca, read and commented on the manuscript, much to the benefit of the final version.

But deep as is my debt to friends and family, I cannot burden them with responsibility for what is in the book. In this an author can only emulate Sir Thomas More on the occasion of his execution. Approaching the steps of the scaffold, he asked the lieutenant to give him a hand going up, but quickly added, Coming down, I will shift for myself.

JOHN W. GARDNER

INTRODUCTION

In the 1930s, Senator Huey Long, The Kingfish, set new standards of demagoguery in this country with his slogans Every Man a King and Share the Wealth. The phrases were politically potent for Longs constituency, but also widely parroted in a humorous way. So it did not surprise me when, as a young professor, I encountered them one day in altered form on the blackboard of my classroom. It was the day of the final exam, and someone had scrawled on the board Every Man an A-Student! and below it Share the Grades!

It was all in fun, and the culprit turned out to be one of my best students. But the phrases ground themselves into my mind. Lurking behind the words were some interesting social meanings. It was not hard to detect in the educational world of the 1930s echoes of the same equalitarianism that rang in those phrases.

The subject has never ceased to interest me. This is a book about excellence, more particularly about the conditions under which excellence is possible in our kind of society; but it is alsoinevitablya book about equality, about the kinds of equality that can and must be honored, and the kinds that cannot be forced.

Such a book must raise some questions which Americans have shown little inclination to discuss rationally.

What are the characteristic difficulties a democracy encounters in pursuing excellence? Is there a way out of these difficulties?

How equal do we want to be? How equal can we be?

What do we mean when we say, Let the best man win? Can an equalitarian society tolerate winners?

Are we overproducing highly educated people? How much talent can the society absorb? Does society owe a living to talent? Does talent invariably have a chance to exhibit itself in our society?

Does every young American have a right to a college education?

Are we headed toward domination by an intellectual elite?

Is it possible for a people to achieve excellence if they dont believe in anything? Have the American people lost their sense of purpose and the drive which would make it possible for them to achieve excellence?

I have discussed these matters with a great variety of individuals and groups throughout the country, and I find that excellence is a curiously powerful worda word about which people feel strongly and deeply. But it is a word that means different things to different people. It is a little like those ink blots that psychologists use to interpret personality. As the individual contemplates the word excellence he reads into it his own aspirations, his own conception of high standards, his hopes for a better world. And it brings powerfully to his mind evidence of the betrayal of excellence (as he conceives it). He thinks not only of the greatness we might achieve but of the mediocrity we have fallen into.

These highly individual reactions to the word excellence create difficulties for the writer or speaker concerned with the subject. When one has had his say, someone is certain to mutter, How could he talk about excellence without mentioning the Greeks? And another, He didnt say a word about the plight of the artist...Nor teachers salaries...Nor the organization man!

It isnt just that people have different opinions about excellence. They see it from different vantage points. The elementary school teacher preoccupied with instilling respect for standards in seven-year-old will think about it in one way. The literary critic concerned with understanding and interpreting the highest reaches of creative expression will think of it in a wholly different way. The statesman, the composer, the intellectual historian each will raise his own questions and pose the issues which are important for him.

It will help the reader to know what my own vantage point is. I am concerned with the social context in which excellence may survive or be smothered. I am concerned with the fate of excellence in our kind of society. This preoccupation may lead me to neglect some of the interesting and perplexing problems of excellence as these confront the specialist striving for the highest reaches of performance in his particular field. I am sorry that such neglect must occur, but I leave its repair to other writers. This book is concerned with the difficult, puzzling, delicate and important business of toning up a whole society, of bringing a whole people to that fine edge of morale and conviction and zest that makes for greatness

Next page