For Maud and Noah

And Mum and Dad

It required years of labour and billions of dollars to gain the secret of the atom. It will take a still greater investment to gain the secrets of mans irrational nature.

Gordon W. Allport, The Nature of Prejudice, 1954

There is no reason for you to become like white people and there is no basis whatever for their impertinent assumption that they must accept you. The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them.

James Baldwin, Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation, The Fire Next Time, 1963

Keep on movin. Dont stop, like the hands of time. Click clock

Soul II Soul, Keep on Movin, 1989

Contents

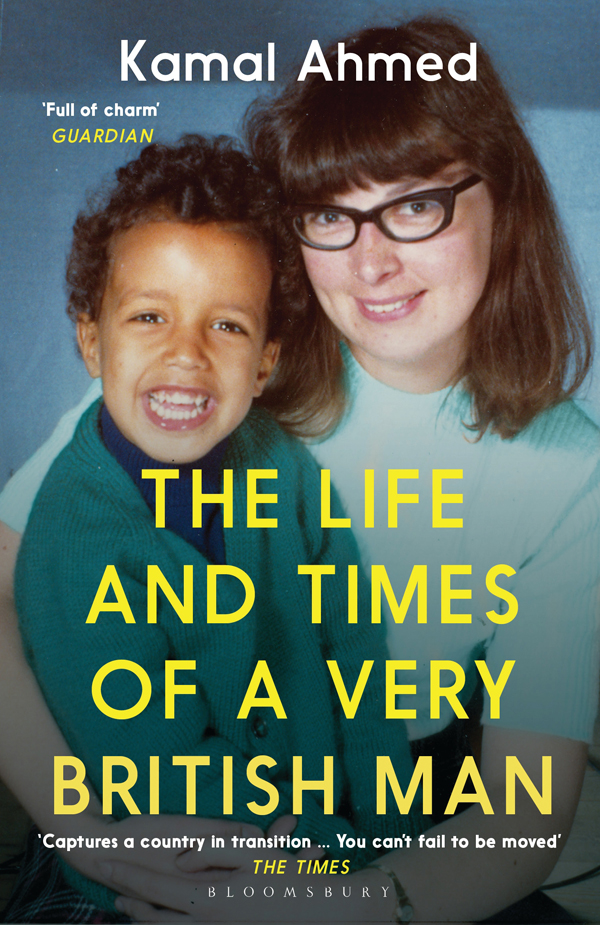

I have six photographs of my father.

Which is not many, really, is it? Given that he is responsible for one half of me.

They are old photographs from the 1960s when I am a little boy and he is a svelte young man in drainpipe trousers and a white wool, roll-neck jumper. His skin is dark, ebony.

Cool. So very, very cool.

Each photograph is black and white with a thick, white border.

One is of my father with a lawnmower, looking proud. There are not that many men from Omdurman, Sudan, who knew what a lawnmower was. Not then not in the 1960s, before you could type lawnmower into Google. He is leaning back with a ta-da! look on his face, hips pushed forward with a flourish, shoulders flung back.

A matador with a Qualcast.

Another is with me, a baby in his arms. My father is laughing as I giggle out of control, being tickled. There is an older lady in the picture, almost cropped out, with horn-rimmed spectacles, a sensible 1950s dress and a grey cardigan. Her skin is soft, pale, white.

Thats my grandmother.

Beloved, wise, kind a woman who eschewed harsh words and argument, passions at odds with a certain type of quiet Englishness that imbued her very being. As different from my father as water is from fire.

A third picture sees my father and me sitting on a drystone wall: I am older, maybe three, which would place the photograph around 1970. I am wearing a striped top. In another we are both looking out from a castle window. A proper English castle with turrets. Its a place called Berry Pomeroy, near Torquay.

The fourth and fifth are similar, from a set all taken on the same day.

The final photograph is on a moor, Dartmoor, also in Devon. The sun is out. We are on holiday. I am sitting on my fathers knee; he in the classically inappropriate dress of the immigrant recently arrived in England and ready for a day out in the countryside he has read so much about at school, thousands of miles away. Leather slip-ons are not the ideal footwear for a walk across scrubby, steep grassland dotted with heather and sheep poo. Even if they are paired with Pringle socks.

My father is in his late twenties.

Forty years later he will be dead.

And these are all the photographs I have of him six four-inch squares of history that I do not remember because at that age memory has no longevity. At the age of three, the narrative of our life is largely lost to the immaturity of our brains.

I keep the pictures in an envelope. On the front of the envelope is the name Elaine, written in fountain pen. Elaine is my mother. Its my Auntie Marjories writing. My Auntie Marjorie is from north Wales. She must have sent them to her sister-in-law many years ago.

Not many young men from Saharan Africa ended up holidaying in the south-west of England in the era of the Beatles and Harold Wilson with a pipe. Not many grammar school-educated women from a small village in the north of England married men from Sudan in an era when wearing a miniskirt was a flag of social rebellion. And even fewer had children. So, there werent many people like me around in those days, looking out from castle windows, eyes expectant, smiling.

Not many at all.

The debate of our age is the debate about identity. Who are we? Why do we do what we do? Why do I like this thing? And not like that? Who are the in-group? The me group. And who are the out-group? The other.

For anyone not white in a country which most assuredly is, much of that identity is expressed via one obvious fact. The colour of the persons skin.

In my case, brown. Not a big definite colour like white or black, but a tertiary colour. A secondary colour. A mixed colour.

And hang onto that thought, because it throws up a whole host of competing trends and tides as we try to make sense of those big questions about who we are, where we live and what that says about us the British. Because I most definitely am British. A Very British Man. Not a Very English Man, oddly, because English seems more exclusive, less me. British is that most malleable of words, attachable as easily to Britain First (Taking Our Country Back) as it is to British values and British Summer Time, which is more my kind of Britain, lazy days lying in sun-kissed meadows. Comfortable, soft Britain.

Now and this is the odd thing given the importance of that outer signal if a surgeon did not know the colour of our skin, she or he would find it impossible to deduce from rummaging around in our insides, looking at the texture of our blood in a test tube or counting how many teeth we have. Strip off that obvious layer and we are all the same a pretty remarkable set of electronic impulses, muscle tissue and organs which come together to form a human being and member of the one in-group that is strictly defined and impossible to dispute, the human race Homo sapiens. Wherever we live, whatever our background, whatever our ethnicity, we laugh at jokes that are funny and feel sadness when someone we love dies.

And here is a second thing that is worth considering. All human beings are born prematurely in comparison with the rest of the mammal world, and as such are a relatively blank canvas, emotionally. That the vast majority of our brain development happens in the world around us (our brain doubles in size in the first year of life) rather than during pregnancy, means that inputs from that outside world via material culture (tools) and emotional culture (society) are vital. If we wanted to arrive in the world with the cognitive ability the cognitive smarts of a chimpanzee newborn, pregnancy would need to last about twenty-one months. My guess is a rather limited number of mothers would gladly sign up to such an arduous metabolic and mental task.

This short gestation, relatively helpless childhood and long adulthood, gives us an ability unique in the animal kingdom. We learn about life and who we are in the outside world and we decide how to make sense of it. Our brains are not hardwired from birth. No one is born prejudiced, born with a desire to put some other group to the sword. Our beliefs and ideas become hardwired via the stories we tell ourselves and the cultures we build, and those stories and cultures are ultimately under our control and can change if we will it.

We are evolutionarily special in our ability to identify a problem and come up with a solution because we have given ourselves so much thinking time. Our races attempts to do so have led to world religions, wars and scientific breakthroughs that take the breath away. And, as Yuval Noah Harari argues in Sapiens, if you can create myths, of differences, of superiority, of otherness, of the danger of the out-group, you can also unmake them, in surprisingly short order. In 1789 the French population switched almost overnight from believing in the myth of the divine right of kings to believing in the myth of the sovereignty of the people, Harari writes. As we British say of the weather: if you dont like it, a different lot will be along in a minute.