Cover design by ::maybe

This collection copyright 2005 Ocean Press

Preface 2005 Adrienne Rich

Introduction 2005 Armando Hart

Socialism and Man in Cuba 2005 Ocean Press and the Che Guevara Studies Center

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-9872283-3-8 (e-book)

Library of Congress Catalog Card No: 2004106393

First Printed 2005

Reprinted 2007, 2015

Also published by Ocean Sur in Spanish as Manifiesto.

PUBLISHED BY OCEAN PRESS

Australia: PO Box 1015, North Melbourne, Victoria 3051, Australia

E-mail:

USA: E-mail:

OCEAN PRESS DISTRIBUTORS

United States and Canada:Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

Tel: 1-800-283-3572 www.cbsd.com

Australia and New Zealand:Palgrave Macmillan

E-mail:

UK and Europe:Turnaround Publisher Services

E-mail:

Mexico and Latin America:Ocean Sur

E-mail:

| www.oceanbooks.com.au |

contents

adrienne rich

KARL MARX, ROSA LUXEMBURG AND CHE GUEVARA

If you are curious and open to the life around you, if you are troubled as to why, how and by whom political power is held and used, if you sense there must be good intellectual reasons for your unease, if your curiosity and openness drive you toward wishing to act with others, to do something, you already have much in common with the writers of the three essays in this book.

The essays in Manifesto were written by three relatively young people Karl Marx when he was 30, Rosa Luxemburg at 27, Che Guevara at the age of 37. Born into different historical moments and different generations, they shared an energy of hope, an engagement with history, a belief that critical thinking must inform action, and a passion for the world and its human possibilities. That society as it was materially constructed would have to undergo radical change in order for such possibilities, stifled or denied under existing conditions, to be realized, all three affirmed in their lives and work. They were educated, reflective people who sharpened their thinking powers on that endeavor.

Marx lived most of his prodigiously creative life in poverty and exile. Rosa Luxemburg and Che Guevara were targeted and assassinated for their intellectual and active leadership in socialist movements. Any one of them might have led the life of a relatively Or, as Che told a group of Cuban medical students and health workers in 1960:

The revolution is not, as some claim, a standardizer of collective will, of collective initiative. To the contrary, it is a liberator of human beings individual capacity.

What the revolution does do, however, is to orient that capacity.

None of them was thinking in isolation or in a historical vacuum. They had the past and its earlier thinkers to learn from and critique; they observed and participated in social movements; they worked out and argued ideas and strategies, sometimes fiercely, with comrades (Marx especially with Friedrich Engels, Luxemburg with Leo Jogiches, Clara Zetkin, Karl Kautsky and others of the German Social Democratic Party, Che Guevara with Fidel Castro, other Latin Americans and with leaders of the nonaligned nations). They saw themselves not as public intellectuals but as witnesses of and contributors to the growing consciousness of a class which produced wealth and leisure without sharing in it, a class fully capable of reason and enlightened action, though often lacking the formal education that could lead to political power.

That the working people who produced the wealth of the world could move toward political and economic emancipation, they did not simply believe but saw as a necessary evolution in human history. Revolutions were all around them, mass movements, strikes, international organizing. But it was not just the temper of their times that drew them into activity. (Many professionals and writers, especially when young, have been attracted by a moments flaring promise of social change, only to pull back as the windchill of opposition begins to freeze the air.) Rather, they observed around them the accelerating relationship between private wealth and massive suffering, capitals devouring appetite for expansion of its markets at whatever human cost (including its wars); and in that awareness they also saw the meaning of their lives.

As a young medical student traveling through Latin America, Che Guevara noted this concretely:

I went to see an old woman with asthma The poor thing was in a pitiful state, breathing the acrid smell of concentrated sweat and dirty feet that filled her room, mixed with the dust from a couple of armchairs, the only luxury items in her house. On top of her asthma, she had a heart condition. It is at times like this, when a doctor is conscious of his complete powerlessness, that he longs for change: a change to prevent the injustice of a system in which only a month ago this poor woman was still earning her living as a waitress, wheezing and panting but facing life with dignity.

It was Marx first of all who described how capital not only dispossesses and forces the vast majority of people to sell themselves piecemeal, but contains, ultimately, its own undoing:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the netherworld whom he has called up by his spells.

But he first lays forth an exposition of the history of capitalism, the emergence of bourgeois or owning-class power and the effects of that power, a panorama so prescient of 21st century social conditions that it transcends its own moment of writing. As Che was to observe in 1964:

The merit of Marx is that he suddenly produces a qualitative change in the history of social thought. He interprets history, understands its dynamic, foresees the future. But in addition to foreseeing it (by which he would meet his scientific obligation), he expresses a revolutionary concept: it is not enough to interpret the world, it must be transformed.

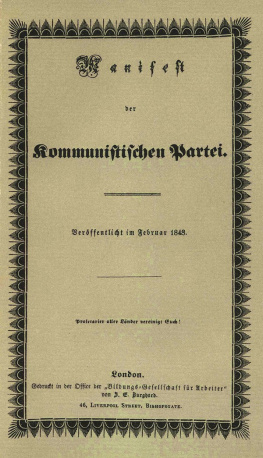

And in fact, over more than 150 years The Communist Manifesto has become the most influential, most translated, reprinted (and demonized) single document of modern history. Its a work of extraordinary literary power fused with historical analysis; a document of its time yet resonant, as we see here, for later generations. A document which can be, has been, critiqued and argued with even by its author but which will be carried into any future that is bearable to contemplate.

Marx, Luxemburg and Guevara were revolutionaries but they were not romantics. Their often poetic eloquence is grounded in their study and critical analysis of human society and political economy from the earliest communistic arrangements of prehistory to the emergence of modern capitalism and imperialist wars. They did not idealize past societies or attempt to create marginal communities of lifestyle purists, but beginning with Marx they scrutinized the illusions of past and contemporary reformers and rebels in the light of history, aware how easy it can be for parties and leaders to lose momentum, drift off and settle down with existing relationships of power. (It is this kind of compromise that Luxemburg addresses in

Next page