ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I t is my privilege to extend thanks to the individuals whose expertise played a key role in compiling the list of scientists profiled in this volume. At the New York Academy of Sciences, Irwin Gittelman, Marguerite F. Levy, Louis Muschel, Margaret A. Reilly, David G. Black, and Sylvia Slote all reviewed the growing roster and made valuable suggestions. I also wish to thank the academys development officer, Craig Purinton, who was unfailingly helpful and courteous. I owe special thanks to Adnan Waly, the experimental physicist, who provided advice and valuable insight, based on both his own wisdom and personal acquaintance with the major figures of twentieth-century physics.

Where possible, I offered contemporary scientists an opportunity to correct factual mistakes in their respective profiles. For their courteous help my thanks are due to Hans Bethe, Noam Chomsky, Francis Crick, Gertrude Belle Elion, Claude Lvi-Strauss, Lynn Margulis, Ernst Mayr, Frederick Sanger, Edward Teller, and Edward O. Wilson. Individual chapters were also reviewed by David Cassidy, Gale Christianson, Bruce Chandler, Jeff Cohlberg, Sue Massy, Alan Rocke, K. C. Wali, and Deborah Weir. A sensitive reading of the entire manuscript by Donald J. Davidson was invaluable. I am grateful to all, and add that the errors which remain are mine alone.

During early work on this project I was inspired by reading Stephen G. Brushs History of Modern Science: A Guide to the Second Scientific Revolution as well as by his illuminating article, Should the History of Science Be Rated X? Professor Brush kindly reviewed the list for this volume and made important suggestions My gratitude is also due Keith Benson of the History of Science Society at the University of Washington. The veteran science writer Stephen S. Hall also made valuable recommendations, as did lain Boal and Lawrence Creshkoff. For photo research I am grateful to Jocelyne Barque as well as Inge King. For her patience and skill in shepherding the manuscript through production, I thank Arline M. Cooke. My thanks and appreciation, as well, to Fred Korndorf and to my colleagues at the Writers Room.

For over fifteen years at Current Biography I have had the pleasure to work with Judith Graham as well as with her predecessor, Charles Moritz, and take this opportunity to thank them for introducing me to a great variety of interesting people, scientists among them.

Finally, I could not have found a better editor anywhere in publishing than James Ellison.

INEXCUSABLE OMISSIONS, HONORABLE MENTIONS, AND ALSO-RANS

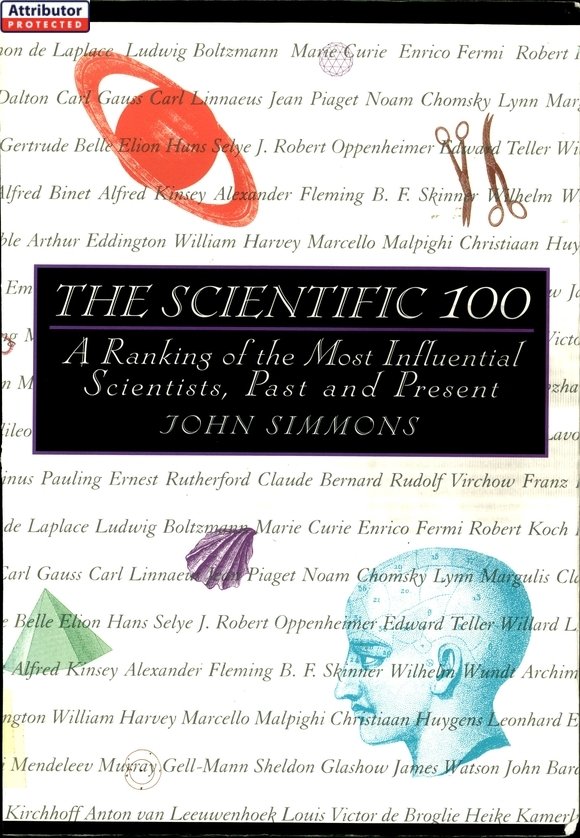

S ome explanation is in order for those famous and influential scientists not included in this book. Above all, the decision to begin with Isaac Newton imposed a structure which restricted earlier figures to those who made specific accomplishments and revolutionary advancesNicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, for example. Aristotle is of the greatest importance in the history of science, but his contributions are due to his pervasive and historical, rather than direct, influence. Similarly, the omission of Ren Descartes. He certainly would belong in this book for his overall significance and contribution to method, but no major enduring discovery belongs to him. About the same may be said of Francis Bacon, who until the twentieth century was considered among the greatest scientists ever.

British science, particularly, offers many examples of scientists before Newton of formidable influence but who receive only a mention here, including Robert Boyle, William Gilbert, Henry Cavendish, and Edmond Halley. Further back in history, there is a class of scientific pioneers whose absence should not go without mention. Just to name a few: Hippocrates, Galen, Ptolemy, and Paracelsus, along with the great figure of Arab science, Alhazen.

Omissions in physics are many. Nothing can adequately explain the absence of Josiah Gibbs or Lord Kelvin, unless you asked Charles Darwin, who liked to call the latter an odious scepter for his pious views on the age of the earth. Heinrich Hertz and Alessandro Volta had units of electricity named after them, which surely ought to be sufficient to earn them a place in the centumviratebut wasnt. The major architects of quantum theory are includedwith exceptions, such as Wolfgang Pauli. Richard Feynman is here, but not Julian Schwinger or Sin-Ituro Tomonaga, the two other major theorists behind renovated quantum electrodynamics. A few omissions have not only the consolation of the Nobel Prize but also pride of kinship, such as William Henry Bragg and his son, Sir Lawrence Bragg.

Francis Crick once remarked that of all the physical sciences, chemistry is most resistant to popular treatment. Not to be gainsaid by this book, in which neither Claude Berthollet nor Jons Berzelius nor Joseph Priestley is included. In the twentieth century, it is remarkable but true that no place was available for either the prolific organic chemist Derek Barton or Gilbert N. Lewis, whose work on the atom meant much to Linus Pauling.

Astronomy, by contrast, has always had its great figures who were also popular and widely beloved, such as Stephen Hawking. It is unfortunate that Roger Penrose could not be included, nor Fred Hoyle, nor John Wheeler.

The various branches of biology have produced a pantheon of remarkable figures. Before Darwin, Louis Agassiz, for discovering the ice age, and Georges Cuvier, for comparative anatomy and paleontology, were exceptionally significant. Following The Origin of Species, Hugo de Vries, who rediscovered Gregor Mendel and suggested the theory of mutations, is a notable omission, but there are many others: J . B. S. Haldane and Julian Huxley, for example. Among contemporary figures it is unfortunate a place could not be found for, among others, Stephen Jay Gould or Richard C. Lewontin.

What holds for physics is true of molecular biology. But if George Gamow, who worked in both disciplines, is not here, it might be understood that there was no room either for Salvador Luria, Oswald Avery, or Jacques Monod. Although Frederick Sanger is included for his basic contribution to unbuttoning the human genome, why not Walter Gilbert?

Finally, it should be obvious that only certain figures in the history of medicine can be found here. The discovery of insulin by Frederick Banting and Charles Best has often been told but is here neglected. John Enders deserved to be included for his work on immunology, and I especially regret the space not accorded Gerald Edelman, whose fascinating research in brain science has augmented his great discoveries in immunology. It was also painful to exclude Henry Dale, who discovered acetylcholine, as well as Rita Levi-Montalcini, who discovered nerve growth factor. From the chapter on Jonas Salk, the absence of Albert Sabin should be apparent.

These are only a few of the omissions from that class of scientists whose long reach into nature extends beyond the laboratory bench and scholarly enclave, not only to experiment, observe, and demonstrate, but even to shape our perception of the world.

PICTURE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Every effort has been made to locate the copyright holder of the photos used in The Scientific 100. Some illustrations and photos are in the public domain.

Courtesy Austrian Institute: Ludwig Boltzmann, Sigmund Freud, Erwin Schrdinger

Courtesy Bantam Books: Stephen Hawking

Courtesy Biographees: Noam Chomsky, Claude Lvi-Strauss, Lynn Margulis, Frederick Sanger

Courtesy Burroughs-Wellcome: Gertrude Belle Elion