Dhaval Kulkarni is a Mumbai-based journalist with over fifteen years of reporting experience across brands like the Times of India, Hindustan Times, the Indian Express, New Indian Express and DNA.

He writes on a broad range of subjects like governance and politics, caste, identity and social movements, environment and forests, health, infrastructure, heritage, culture and archaeology. He also reviews books.

Preface

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds worth of distance run,

Yours is the Earth and everything thats in it,

Andwhich is moreyoull be a Man, my son!

Rudyard Kipling, If

Journalists have the rare privilege of watching history unfold.

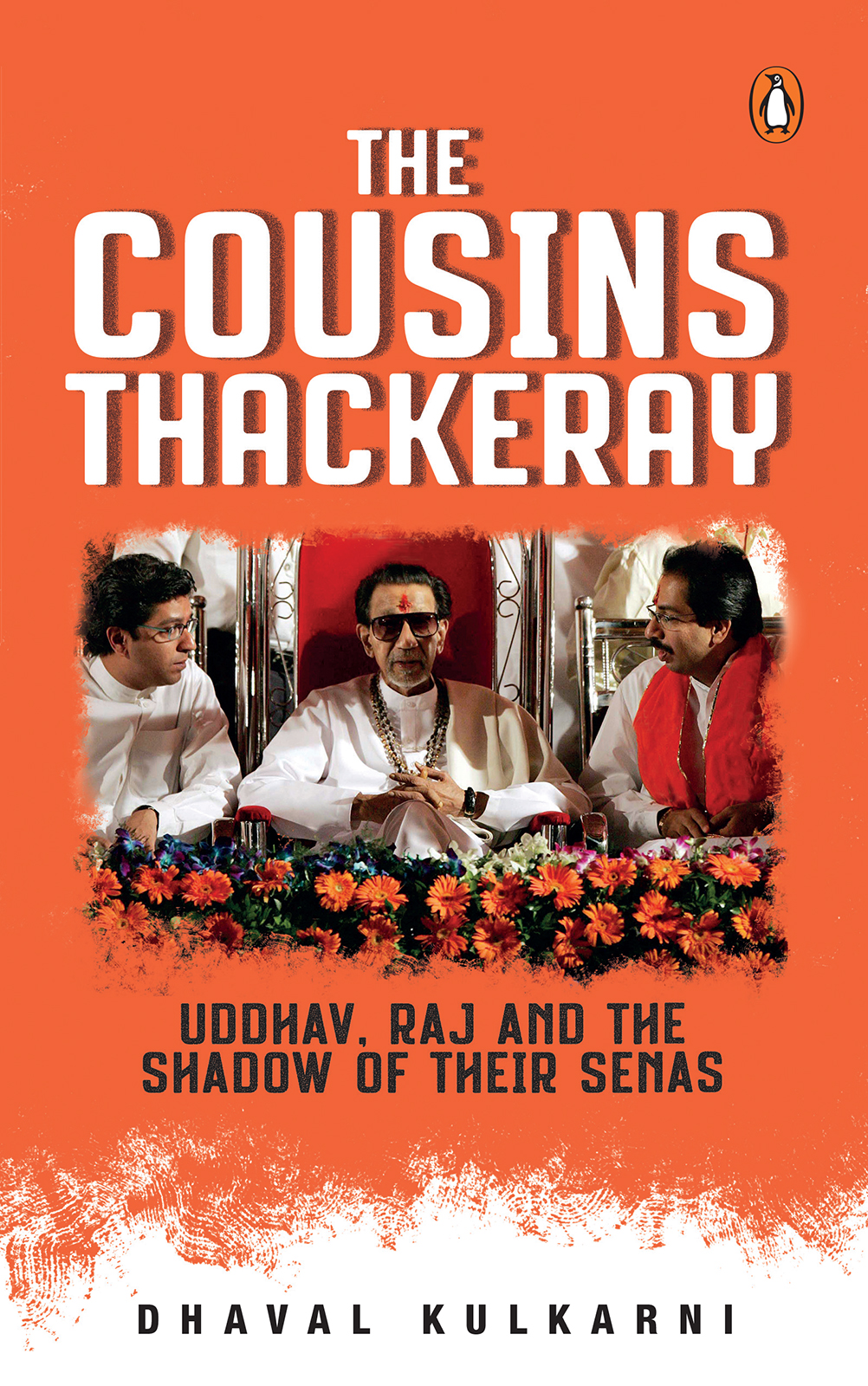

As a reporter who has covered the Shiv Sena and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS) for over a decade, this book was born out of a desire to break the tyranny of 400-word news reports and place these political developments in the larger matrix of social, cultural and economic disruptions.

This book, the idea for which was germinating in my mind over the years, attempts to go beyond merely recording events by delving into the processes that shape them. For instance, why do these nativist movements, which claim to uphold the rights of the sons of the soil, strike a chord with a large section of the toiling masses?

That there was immense curiosity about both Uddhav and Raj Thackeray, even on foreign shores, was evident when the author visited Pakistan in 2011 as part of a media delegation. Then, the highest number of questions from members of the local media, civil society and people at large, were about these two estranged cousins and their uncle, Shiv Sena chief Bal Thackeray. This book is an attempt to satiate some of this curiosity by providing a deep-dive narrative into the political lives of Uddhav and Raj Thackeray, and their parties.

This is also an attempt to place before a larger, multilingual audience the life and times of that autodidact, Prabodhankar Keshav Sitaram Thackeray. His strength of character stands in contrast to the politics played by these two parties who form the focal point of our narrative and under whose watch the Marathi manoos in Mumbai has retreated to the margins and beyond.

I have unsuccessfully tried to get both Uddhav and Raj Thackeray to open up about their version of events for this book.

As I juggled professional commitments and work on this book, with a tough deadline to match, these lines from Kiplings poem quoted at the beginning of this preface, often came to my mind. It is for the reader to judge if I have been successful in this effort.

1

The History of the Thackeray Family and Prabodhankar Thackeray

Though a battles to fight ere the guerdon be gained,

The reward of it all.

I was ever a fighter, soone fight more,

The best and the last!

Robert Browning, Prospice

The modest Kadam Mansion at 77-A, Ranade Road, Dadar West, Mumbai, has been demolished and a new structure takes shape at the sitean inevitable result of the old making way for the new. But the political legacy that was born in this building, located in a by-lane off the historic Shivaji Park precincts, continues to endure.

It was here that Prabodhankar Keshav Sitaram Thackeray resided with his large brood, including his sons Bal and Shrikant. It was in this ground-floor flat that the Shiv Sena was born in 1966.

Prabodhankars contribution to Maharashtras social reform and anti-caste movements remains seminal. Born on 17 September 1885 at Panvel in Kulaba (todays Raigad district) near Mumbai, Prabodhankar launched the weekly Prabodhan (Enlightenment) in 1921. Though it ran for just five years, Prabodhankar was permanently prefixed to his name.

In his autobiography, Majhi Jeevangatha (The Story of My Life), the Thackeray patriarch notes that his family, which belonged to the Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhu (CKP) caste, originally hailed from Pali village in the small principality of Bhor. The state was ruled by the Pantsachiv dynasty.

He recounts that the Thackeray familys ancestors added Dhodapkar to their surname as one of them was the killedar (chief) of the Dhodap Fort near Nashik, but this was dropped by Prabodhankars father.

Shaped like a lingam, the fort was ceded to the Marathas by the Nizam of Hyderabad in 1752 by the Treaty of Bhalki.

After the British besieged the fort, perhaps in the later period of the Peshwa rule, this Thackeray family ancestor fought bravely despite running out of provisions and was ultimately killed.

Castes and their varying fortunes

Though Prabodhankar was a leading light of the Bramhanetar (non-Brahmin) movement, which sought to counter the overarching influence of Brahmins in Maharashtra, his autobiography notes a family fable. When Dhodap Fort was about to fall, his ancestor was saved by a Brahmin who mysteriously appeared before him, lauded his bravery and teleported him to his village at Pali! To commemorate this incident, the Thackeray family worshiped two silver imagesone of a warrior, another of a Brahmin.

After his brothers insisted on dividing the family property at Pali, Prabodhankars great-grandfather Krishnaji Madhav Appasaheb relinquished his claim over it and left for Thane where he worked as a lawyer, making his reputation as an upright, helpful man.

His son, Ramchandra aka Bhikoba Dhodapkar, a devotee of the Goddess, found employment in the courts and was transferred to the small causes court at Panvel where he lived until his death. His wife (Prabodhankars grandmother) Sitabai, called Bay, worked as a pro bono midwife who did not discriminate on the basis of caste and religion in the line of duty. Bay was a woman ahead of her time and was disgusted by the practice of untouchability.

... our Thackeray family was very poor. In three to four generations preceding me, there was no information of anyone owning even an inch of property. However, we had a hutment-like dwelling in Panvel village, where I was born, says Prabodhankar, while describing himself as a self-made man.

The year 1818 saw the fall of the Chitpavan Brahmin Peshwas, whose twilight years were marked by moral turpitude and caste-based excesses. The Peshwa reign was supplanted by the East India Company (1818) and later the British Crown (1858), and Brahmins eased themselves into the new order by virtue of their access to education and centres of power.