Contents

Guide

First published in 2021 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Les Wilson 2021

The moral right of Les Wilson to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act, 1988.

ISBN 978 1 78885 28 7 6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any other form without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

In memory of

Carl Reavey (19562018)

and for

Ivy Jean Hunter (born 22 August 2019)

For me starting the day without a pot of tea would be a day forever out of kilter.

Bill Drummond, $20,000

Tea is the best substance in the world. I love tea. It makes me feel jolly tea is the substance.

Billy Connolly

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

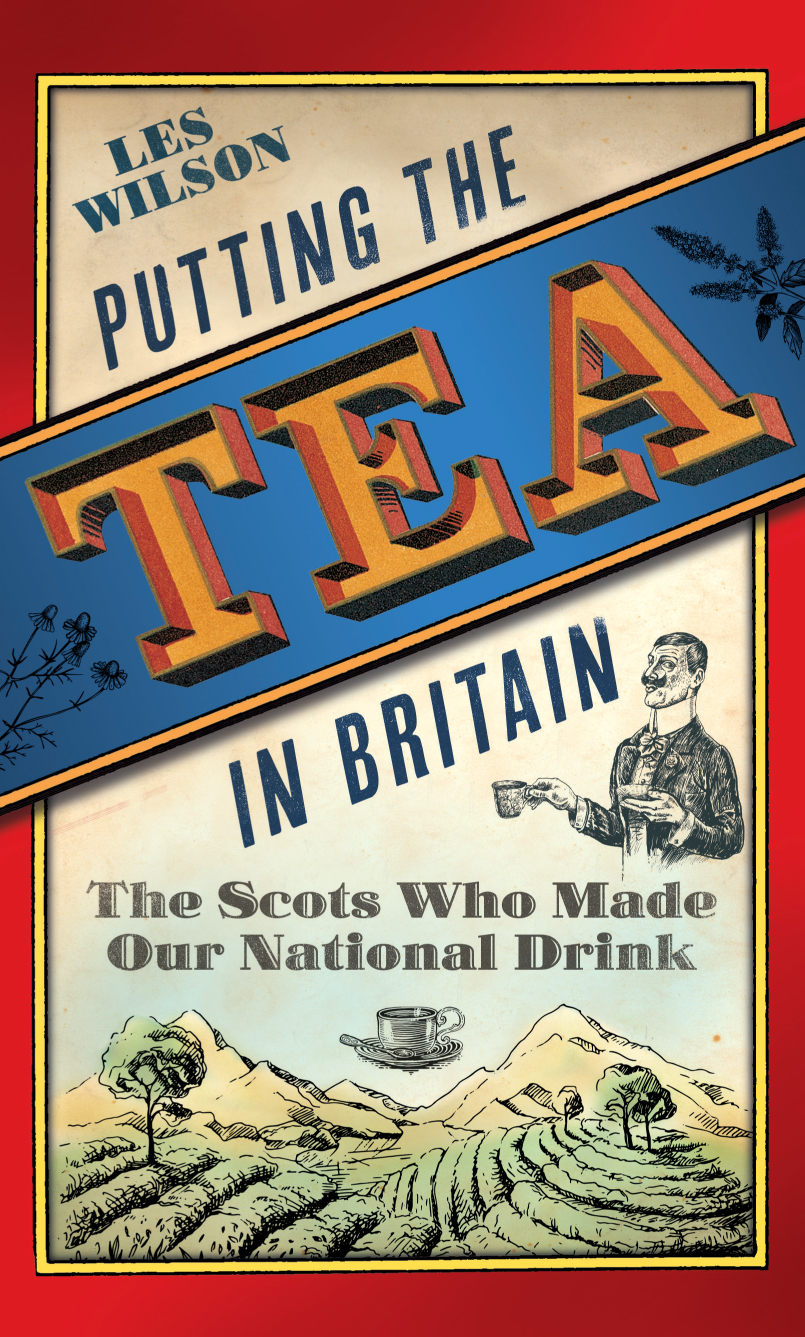

Two centuries ago, all the tea drunk in Britain came from China. Tea bushes, and the techniques of preparing their leaves, were the Celestial Empires jealously guarded secret. Any Chinese who betrayed them to the Western barbarians faced severe punishment, even death. This book tells how Scots broke that monopoly, made tea Britains and the worlds favourite drink and transformed the histories of China, India, Sri Lanka and much of Africa.

In 1664 the East India Company imported a single chest of tea into Britain from China. But Britain quickly developed a thirst. By 1800, the Company was buying more than 25,000,000 pounds of China tea a year. The self-sufficient Chinese didnt want industrial British manufactured goods in exchange they just wanted silver, and the United Kingdoms reserves were dwindling. In this ignominious age, Britain paid for the tea with Indian opium smuggling opium into China, causing misery for millions, infuriating the Chinese government and igniting two opium wars. A more rational way for Britain to balance its tea-trade deficit was to find somewhere in its vast empire where it could grow its own tea and then acquire the plants and the know-how to make them flourish. Enter a remarkable group of Scotsmen. Essentially, they stole Chinas tea, successfully replanted it in India and then discovered an indigenous tea in Assam. These two different jats (types or castes) of tea were successfully raised in Darjeeling, Assam, South India, Ceylon and Africa breaking Chinas tea monopoly forever.

The seed from which this book grew was planted in Darjeeling, in the foothills of the Himalayas. I have had a long love affair with India, and on a visit to this beguiling region I discovered, to my astonishment, that the first person to grow tea in Darjeeling was a Scottish doctor, Archibald Campbell. Campbell was the son of a gentleman but, as the third son, and being neither the heir nor the spare, had to make his own way in the world. He graduated in medicine at Edinburgh University and joined the East India Company, which eventually sent him to establish a sanatorium and hill station that would provide white sahibs with temporary relief from the sweltering heat of Calcutta. A keen amateur botanist, Campbell planted China tea bushes in the garden of his Darjeeling estate. Campbells tea thrived, and within a decade other Brits had followed his example and tea gardens sprouted up all over Darjeelings hillsides.

Archibald Campbell is a neglected figure. He came from Islay, the Inner Hebridean island that has been my home for many years yet I had never heard of him. He founded Darjeeling but it was only on my second visit to the town that I discovered who he was and what he had done. Intrigued, I began to read and enquire. Very quickly, I discovered that an extraordinary proportion of the men who caused tea to become the favourite drink of half the world were Scots.

Here is a very brief list:

Islays Archibald Campbell.

Robert Fortune, a Borders lad o pairts, who disguised as a Chinese man risked arrest, robbery, piracy and murder to bring tea plants to the British Empire.

William Melrose, the son of an Edinburgh grocer and a pioneer trader in a tiny European enclave in hostile Canton.

Edinburghs Bruce brothers Robert and Charles who discovered that wild tea grew in Assam, thereby becoming the fathers of another great tea region.

Robert Kyd, the Angus-born soldier who founded Calcuttas botanic garden, where tea was first nurtured in British India, and the subsequent dynasty of Scottish botanists who succeeded him as the gardens superintendents.

James Taylor of Kincardineshire, who first grew tea commercially in Ceylon and brought the economy of the island back from the brink of disaster.

Thomas Lipton, who brought affordable tea to the masses and made it our national drink.

Edinburgh gardener Jonathan Duncan, who planted two tea bushes from the citys botanic gardens at the Church of Scotland mission at Blantyre, Malawi; and Henry Brown of Banff, who founded Africas vast tea industry with a handful of seeds scrounged from that mission garden.

These mens stories read like something from Robert Louis Stevenson or Joseph Conrad, but there is a genteel lady to soften this macho crew. The entrepreneurial and artistic Catherine Cranstons fashionable Glasgow tea rooms gave full scope to the imagination of Scotlands most famous architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and his artist wife, Margaret Macdonald, and provided gathering places for unaccompanied ladies at a time when women were clamouring for the right to vote.

And there are the assorted entrepreneurial Scottish mill-owners, grocers, adventurers, soldiers, scientists, planters and chancers who risked their capital, reputations, health and lives for tea What characters! What stories! Tea is interwoven with centuries of Scottish, British and world history. My serendipitous discovery of Archibald Campbell of Islay and Darjeeling sprouted wings.

With such a litany of Scottish names prominent among those who put the tea in Britain (and a good many other places), I quickly came to face the questions: Why Scotland? What was it about the Scots that made them such pioneers? It is clear that the tea men were part of what Professor Tom Devine has called the relentless penetration of Empire by Scottish educators, doctors, plantation overseers, army officers, government officials, merchants and clerics. Essentially, Scotlands tea men were economic migrants, escaping poverty or at least a lack of opportunity at home.

With about 9 per cent of Britains population, Scots at one point held 25 per cent of the British jobs in India and were clearly the right people, in the right place, at the right time. Their relatively small country had recently united with a neighbour that was busy building a global empire. That empire badly needed likely lads white English-speakers, if not necessarily Englishmen to run it. Scots, hungry for betterment, were able to take advantage of that. Their education, an inheritance of the Reformation and the Scottish Enlightenment, had equipped a far greater proportion of Scots than of Englands people to fulfil a wide range of imperial roles.