Contents

Guide

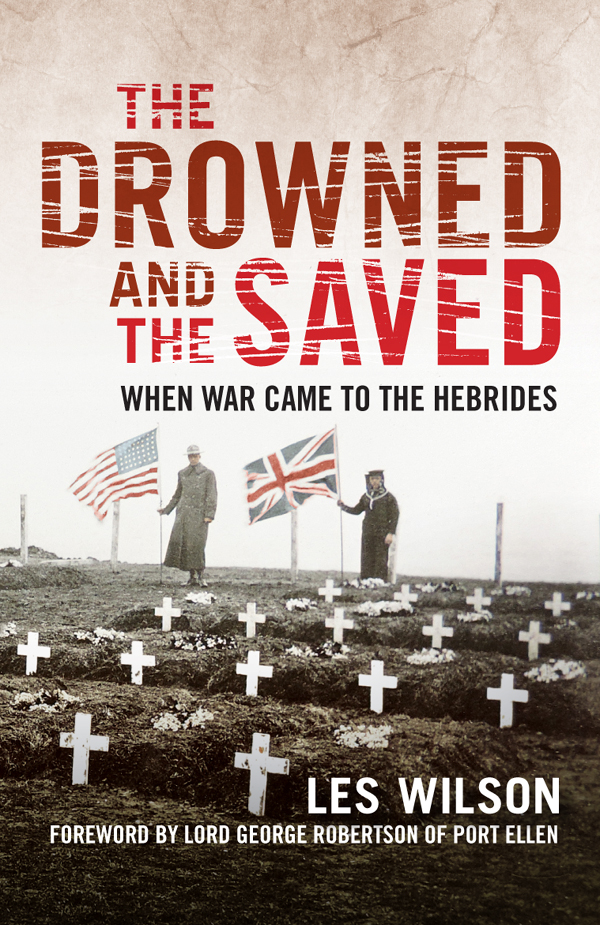

The Drowned and the Saved

Les Wilson is a writer and an award-winning television documentary maker who has specialised in Scottish historical subjects. His work includes films about the Lighthouse Stevenson family; engineer Thomas Telford; writer, adventurer and political activist Robert Cunninghame Graham; the principal chief of the Cherokee nation, John Ross; and the artist who created the monumental Kelpies sculptures, Andy Scott. He has made documentary series about Scotland during World War Two, and the history of the Scottish regiments. He lives on the island of Islay.

Also by Les Wilson:

Scotlands War (with Seona Robertson), Mainstream, 1995

Fire in the Head, Vagabond Voices, 2010

Islay Voices (with Jenni Minto), Birlinn, 2016

THE DROWNED AND THE SAVED

When War Came to the Hebrides

Les Wilson

s

First published in 2018 by Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Les Wilson

The right of Les Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 027 8

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

MBM Print SCS Limited, Glasgow

For Jenni

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Foreword

Lord George Robertson of Port Ellen

Even for a Hebridean island used to some foul weather and occasional wrecked ships, the events of 1918 in Islay must have been especially grim. To experience one major troopship disaster that February was traumatic enough for a small island community already hit severely by casualties on the distant Western Front. But to face another disaster only a few months later was unprecedently awful.

Islay was not rich, it was agricultural and it was quiet. The great boom in Scotch whisky drinking had not yet stimulated the small island distilleries and tourism was in its infancy. To this peaceful rural community was to come a visitation of brutal violence and profound sadness.

The torpedoing of the liner Tuscania, carrying 2,000 troops, in February 1918 brought to the island both dead victims and survivors in huge numbers. It happened in the night, it happened on the remote and inhospitable cliffs and rocks of the Mull of Oa and it brought forth bravery, service, humanity and the resources of the islanders to a quite remarkable degree.

Two hundred soldiers and sailors died. It was the biggest loss of American military lives in a single day since their Civil War. When news hit the US, the shock was considerable.

When the troopship Otranto fell victim to a collision off the western rocky shores of Kilchoman in October of the same miserable year, the last of the so-called Great War, the previous experience was useful. But the double shock was to leave lasting legacies of pain and mourning. Another four hundred perished.

My maternal grandfather, Malcolm MacNeill, was the police sergeant on the island in 1918. With his three constables, he was in effect the public authority on Islay. Yet nothing in his training or experience could have prepared this son of a shepherd from Inverlussa on the neighbouring island of Jura for the challenges he faced on these grim days in the last months of the First World War.

Just a few years earlier, another police constable serving in Port Ellen, Norman Morrison, wrote in his autobiography:

The duties of a country constable on the whole are generally speaking, interesting and pleasant, particularly when one is stationed in a district which is free from crime. Routine work is easy and sometimes even fascinating. To the lover of the beautiful in nature, the life is really an ideal one.

Before patrol cars and an air service and the telecommunications we now take for granted, the scale of the difficulties Sergeant MacNeill faced was simply immense. He had to travel by bike in hellish weather to the remote extremities of the island. He had to organise the rescues, the handling of survivors, the recovery and cataloguing of the dead, the recording of events and the communications from and to the legion of top brass who eventually descended on the scenes of these disasters.

He was not alone in his endeavours, for the scale of the tragedy and its aftermath brought out the very best in a hardy, resilient and resourceful Islay population.

The American Red Cross, on the scene in the weeks after each event, was unsparing in its praise:

It is quite impossible to say too much of the humanity of these peasant people, of their readiness to accept any hardship in the name of mercy, of the gently, steadfast nursing they gave the soldiers, virtually bringing them back to life.

One might quibble with the word peasant, but the sentiment expressed speaks of what these American professionals found when they arrived on the scene.

My grandfather, known to me by the Gaelic word Seanair, bearing the enormous responsibilities of the day, was systematic and diligent in his efforts. His notebook, in copperplate handwriting, accounting for all the bodies, was found in a cupboard of his son Dr Hector MacNeill. It is now in the Museum of Islay Life, and is a remarkable chronicle of profound sadness; his descriptions of often unidentifiable battered corpses cannot leave any reader unaffected.

The reports he had to write each night after his travels (written twice so as to keep a copy) were to be followed by the painstaking follow-up letters to bereaved families. The interment of bodies, the organising of survivors, the identification of the islanders who had opened their homes and shared their food and clothing, the recording of the bravery and sacrifice that were shown all fell to these few local members of Argyllshire Constabulary whose lives were changed forever.

He himself was exceptionally for a country police officer to be honoured after the war with one of the first medals from the newly created Order of the British Empire. That MBE, the property now of his great-grandson another Malcolm MacNeill is also on display in Islays Museum.

I was born in the Police Station in the Islay village of Port Ellen, my father having returned from Second World War service to take up duties as a policeman on the island where his father-in-law had been a police sergeant before him. I went from there, via a life in politics, to become Britains Secretary of State for Defence and then Secretary General of NATO, the worlds most successful military alliance. I saw conflict and witnessed how humanity deals with mass casualties. I am consequently filled with admiration at what my fellow islanders did at that time.

The stories in this book, collected brilliantly by Les Wilson, articulate the dramas of both disasters and show how a rural community rose to the immense challenges of tackling them. We see the kindness of islanders with so little, who gave so much. How they produced clothes and food for the survivors and tenderness and compassion for the dead. How coffins were made, graves dug, a Stars and Stripes made and sewed overnight by local women to ensure the fallen lay under their own flag.