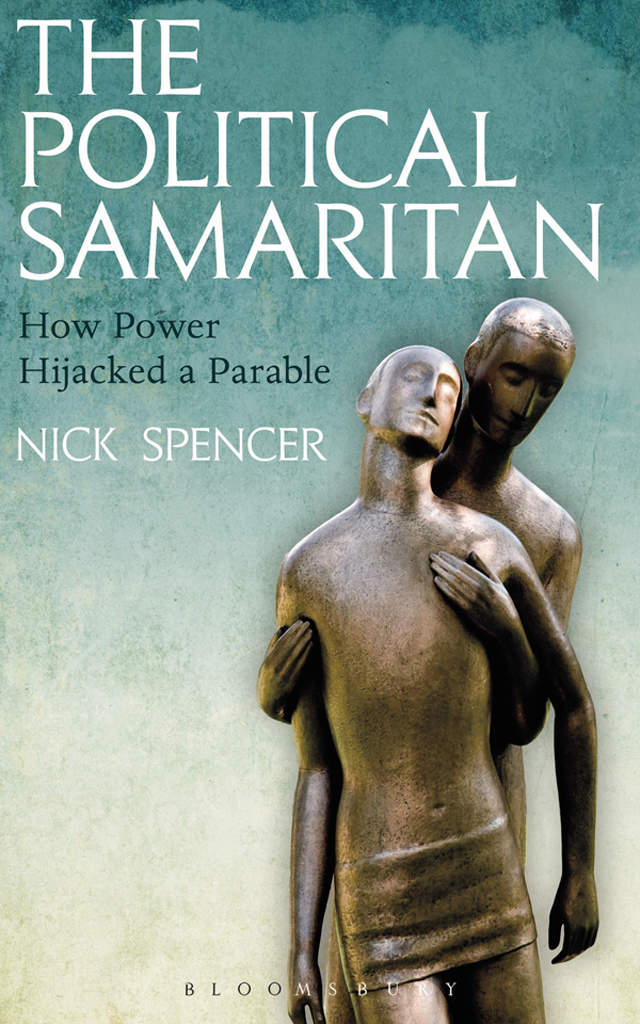

THE POLITICAL

SAMARITAN

THE POLITICAL SAMARITAN

How power hijacked a parable

NICK SPENCER

I will open my mouth in a parable: I will utter dark sayings of old.

PSALM 78.2 (KJV)

Its interesting that nowadays politicians want to talk about moral issues and bishops want to talk politics.

SIR HUMPHREY APPLEBY, THE BISHOPS GAMBIT (YES, PRIME MINISTER)

Contents

25 On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. Teacher, he asked, what must I do to inherit eternal life? 26 What is written in the Law? he replied. How do you read it? 27 He answered, Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind; and, Love your neighbour as yourself. 28 You have answered correctly, Jesus replied. Do this and you will live.

29 But he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, And who is my neighbour? 30 In reply Jesus said: A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half-dead. 31 A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. 32 So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33 But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. 34 He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. 35 The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. Look after him, he said, and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have. 36 Which of these three do you think was a neighbour to the man who fell into the hands of robbers? 37 The expert in the law replied, The one who had mercy on him. Jesus told him, Go and do likewise.

Luke 10.2537

The British should make up their minds: do we or dont we?

Some points, at least, are clear. Britain is not America, a country in which any aspiring politician must, in theory, genuflect before Bible and altar, no matter how dissolute or godless a life they may have lived. The reality is slightly different. Bernie Sanders, for example, made it to within a whisper of the presidential campaign in 2016 despite not attending church or synagogue, rarely speaking about religion, and describing himself as not particularly religious. Contemporary America is not the cultural theocracy its critics imagine. Bernie Sanders notwithstanding, however, it is clear that, as a rule, Americans do.

Nor, by contrast, is Britain France, with its fiercely policed lacit, in which public expressions of Nevertheless, however much God may lurk in the shadowy corners of French politics, it is clear that, by and large, the French dont.

The British, by contrast, drift somewhere between the two in the north Atlantic, quietly, culturally and constitutionally Christian and yet sensibly, shrewdly and soberly secular.

For a generation now, Alastair Campbells best-known aphorism We dont do God has served as shorthand for Britains theo-political mentality: Tony Blair, British politicians en masse, indeed even the entire British public dont, in principle, like to mix religion and politics. The reality is, once again, somewhat murkier.

In the first instance, Campbell himself has often remarked that We dont do God is not only one of his most reused soundbites but also one of his most misunderstood. He never intended the phrase to be a statement of principle, a pronouncement of secular orthodoxy made ex cathedra; rather, it was only to stop a long interview with Tony Blair. Were not getting on to God right now might be an accurate translation.

Anthony Eden was much closer to his fathers atheism than his mothers Anglicanism.

Thereafter, however, there was Harold Macmillan, a lifelong and devout Anglo-Catholic, who took the New Testament with him to the trenches.

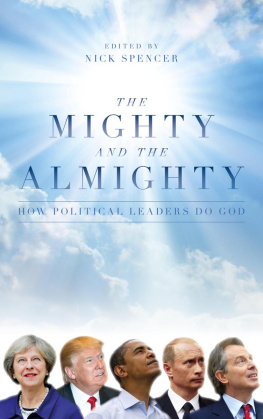

Since Callaghan, British PMs have, if anything, become more religious still. Thatchers fierce late-Victorian Methodism was foundational to her politics. Majors faith was rather more tepid and hesitant. Blair was an adult convert, his communitarian thinking of the 1990s grounded in the personalism of Christian philosopher John Macmurray, filtered through the Rev Peter Thompson at Oxford. Gordon Brown was a son of the manse, albeit one more comfortable talking about his fathers religion than his own, more cultural, Presbyterianism. David Camerons Anglicanism was similarly cultural and undogmatic, famously coming and going like Magic FM in the Chilterns. And Theresa May is a clergymans daughter, a practising Anglican and someone who claims Christianity as foundational to her political worldview. All in all, this is not a list of politicians unaware of or indifferent to God, or keen to exclude him from their political considerations. In this regard, British politics or, at least, those who reach its summit clearly do do God.

And yet, the popular understanding of Alastair Campbells maxim is also right. However pious they may be, British political leaders do seem to have difficulty talking about God. Unlike the people who God berates through the prophet Isaiah, British politicians fail to honour me with their lips, even if their hearts are close to me.

This is not uniformly the case: Thatcher delivered several theo-political lectures; Cameron said a surprising amount about his and his countrys Christianity; Brown was unashamed about the formative role faith played in his politics, and May adopts the same approach. Nevertheless, apart from such occasional rhetoric and personal asides, Tony Blairs post-office remark that its difficult [to] talk about religious faith in our political system... [because if you do] frankly, people do think youre a nutter is pretty much on the mark. Talking God, Bible or religion sets people thinking that you are somehow subverting the proper processes of liberal democracy; in Blairs words: that you like to go off and sit in the corner... commune with the man upstairs and then come back and say right, Ive been told the answer. Worse still, it can sounds like preaching, in the more colloquial sense of that word, imposing your private views on the public, or disrespecting other members of the electorate who dont share your faith.

How far people really do think this is questionable. There are good reasons to believe that the British public is less nervous about doing God than we imagine, not least as a majority of them still choose some form of Christian affiliation when asked. There are equally good reasons to think that the blockage in fact lies with a Be that as it may, the British position seems to be that however much politicians might do God in their hearts and minds, they shouldnt talk about him in public.

For all that, however, God-talk and Bible-bashing, or at least Bible-tapping, remains. This book is about one particular Bible story that remains completely immune to the unwritten guidelines about doing God in public. It is a parable that, in spite of its extremely demanding ethical message one might even say its preachy tone remains astonishingly popular; a parable that, despite its rather disputed meaning, is seized one might even say hijacked by politicians across the spectrum for a bewildering range of purposes; and a parable that retains its power to inspire, in spite, or perhaps because, of the state of our public discourse today.