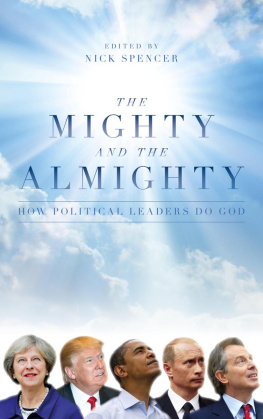

We would also like to thank Tom Slade for his diligence in working through the books footnotes and the team at Biteback for having captured the vision of a book that analysed how political leaders actually do God, rather than assumed it, as so many commentators seem to do.

P aul Bickley is director of political programme at Theos and the author of Building Jerusalem: Christianity and the Labour Party (Bible Society, 2010).

Andrew Connell is a researcher and academic based in Cardiff. His interests include public policy, devolution, and the place of the church in public life. He is the author of Welfare Policy under New Labour: The Politics of Social Security Reform (I. B. Tauris, 2011).

Joseph Ewing is a former Theos researcher and is currently working in public affairs in the third sector.

Maddy Fry is a journalist and a former Theos researcher. She currently works as a policy researcher for the think tank Muslim Engagement and Development and is also writing a novel.

Gillian Madden is a former Theos researcher and is currently completing an MA in Christian leadership, with a particular focus on political theology and the identity of the local church.

Hannah Malcolm is a former Theos researcher and is now living and working at Hilfield Friary, Dorset.

Natan Mladin is a researcher at Theos. He is currently completing a PhD in theology and the arts at Queens University Belfast, with a thesis that explores the doctrine of providence with the aid of theatre studies.

Elizabeth Oldfield is director of Theos and co-author of More than an Educated Guess: Assessing the Evidence on Faith Schools (Theos, 2013).

Henry van Oosterom is a former Theos researcher and is currently studying for a Masters in international security at the Paris School of International Affairs.

Simon Perfect is a researcher at Theos and also a teaching fellow at the School of Oriental and African Studies, where he teaches courses on Islam in Britain and Muslim communities in minority contexts.

Clare Purtill is a former Theos researcher and co-author of Religion and Well-being: Assessing the Evidence (Theos, 2016). She is currently working in Parliament for a Labour MP.

Ben Ryan is a researcher at Theos and the author of a number of reports, most recently A Soul for the Union (Theos, 2016). He is currently editing a book about the ethics of migration policy.

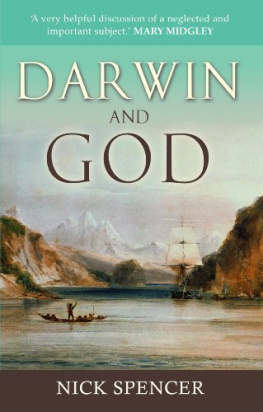

Nick Spencer is research director at Theos and the author of a number of books, most recently The Evolution of the West: How Christianity Has Shaped Our Values (SPCK, 2016). His next book is titled The Political Samaritan: How Power Hijacked a Parable.

NICK SPENCER

W e begin with a horror story.

It is a fringe meeting at the Labour Party conference, September 2015, Monday morning. The British Humanist Association, the UKs premier association of atheists and agnostics, is hosting its no-prayer annual breakfast. This is a lot like the prayer breakfasts that are held annually in Westminster, Washington and many other political capitals, only somewhat smaller and without any prayer.

Breakfast has long gone by the time shadow business secretary Angela Eagle, soon to be a contender for leadership of the Labour Party (and therefore, in theory, the country), launches into an attack on Tim Farron MP. Mr Farron is the new leader of the Liberal Democrats, a party hunted to the point of extinction at the 2015 general election. As the leader of the nations only other centre-left party, one might have expected Ms Eagle to attack Mr Farron for (some of ) his policies or his political principles. But instead, her attack took a different line.

At a time when we have a huge revival of fundamentalist religious belief, she told them, we have a newly elected leader of the Liberal Democrats who is an evangelical Christian who believes in the literal truth of the Bible. He does. He just doesnt want to talk about it a lot because he knows how much it will embarrass his own party.

Ms Eagles vision was alarming, if a little sketchy on the details (if, after all, there has been a huge revival of fundamentalist religious belief in the

With no disrespect to the leader of the Liberal Democrats in the UK (who, for the record, does in fact speak openly about his Christian faith), Mr Farron is rather unlikely to get anywhere near the levers of power. The Liberal Democrats brief union with the Conservative Party in the 201015 coalition government ended in an appallingly messy divorce in which the senior partner got the house and most of the savings, and the junior one the contents of the garden shed and a sleeping bag. Even had they not been left with only eight (now nine) MPs, it is unlikely that any Liberal Democrat party leader will rush into political marriage again. In that regard, it was simply the energy with which Ms Eagle reviled Mr Farrons faith that was unusual. One wonders what she would have said of a parliamentarian who stood a genuine chance of office.

But if her vigour was unusual, the denunciation itself was not. British voters are familiar, some wearyingly so, with the idea that Christianity and politics do not mix. We all know what happens when they do: crusades, inquisitions, invasions, persecution. We free moderns should never forget that religious adversaries are always on the prowl, seeking someone to devour. The price of secular freedom is eternal vigilance, usually of religious people.

Nevertheless, it was the great secular hope that walls of separation, whether constitutionally or culturally erected, and the general decay of Christian belief in the West, would render any theo-political threat dormant, and such eagle-eyed vigilance redundant. Denunciations like that at the no-prayer breakfast would become unnecessary because there would be too few Christians, either in power or in voting booths, for the theo-political menace to scare the secular horses.

Worse, Western politics did not secularise, or more precisely did not secularise as fully and comprehensively as many were expecting. The upsurge in Christian engagement in US politics startled many from the late 1970s; Pope John Paul II played a seminal role in the end of communism in Europe, and even in the somewhat less religious countries of western Europe and Australia, churches remained a part of the political scene, often playing significant walk-on roles themselves. Moreover, as the stories in this volume indicate, Christian political leaders have hardly become less prominent over recent decades, and may, in fact, have become more so. Worse still, those Presidents and Prime Ministers were often open and unapologetic about their faith, and its political significance. It was the stuff of Angela Eagles nightmares.

This book examines the faith of those leaders, twenty-four of them to be precise. While it can be read straight through it can just as profitably be dipped into and cherry-picked for figures who especially appeal to readers.

All but one of its subjects were happy to call themselves Christian, the exception being Vclav Havel, whose writings on theism and ethics are so striking that they demand attention and inclusion, and all held highest office (all but one executive office). Nevertheless, for all their similarity in framing and focus, the chapters in