Teaching Machines

tech.edu

A Hopkins Series on Education and Technology

Teaching Machines

Learning from the Intersection of Education and Technology

Bill Ferster

2014 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2014

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ferster, Bill, 1956

Teaching machines / Bill Ferster.

pages cm. (Tech.edu: A Hopkins Series on Education and Technology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-1540-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-1541-3 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-1540-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-1541-0 (electronic) 1. Educational technology. I. Title.

LB1028.3.F49 2014

371.33dc23 2014004982

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or .

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

For Marilyn B. Gilbert and Charles B. Ferster

Contents

Preface

With the recent media focus on MOOCs, the Khan Academy, and online learning, its easy to forget that people have been looking how technology can facilitate teaching for a very long time. From the early days of educational film, through B. F. Skinners programmed instruction, and into the myriad of e-learning initiatives, educators have been trying to automate instruction.

Albert Einstein once defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. This book is a critical look at past initiatives in automating instruction, so we can understand them from historic, technological, theoretical, economic, and political perspectives and hopefully learn from their successes and failures.

In this book, I examine efforts to automate instruction, provide some overarching commentary, offer insight into current and future uses of instructional technology, and portray people trying to make a difference in education. I tell these stories through the eyes of those who developed and promoted the innovations because many of the same issues and presumptions exist in todays automated instructional tools. The book depicts the people who believed that technology can contribute to learning; in the process, it exposes their thought processes and the hurdles they worked to overcome.

In recounting this history, I will be as objective as is possible but will also provide my personal perspective as a designer, educator, and technologist. I have an odd combination of pessimism about previous efforts to automate learning coupled with respect for the innovators and what technology can bring to society when thoughtfully introduced, and I try to impart both perspectives.

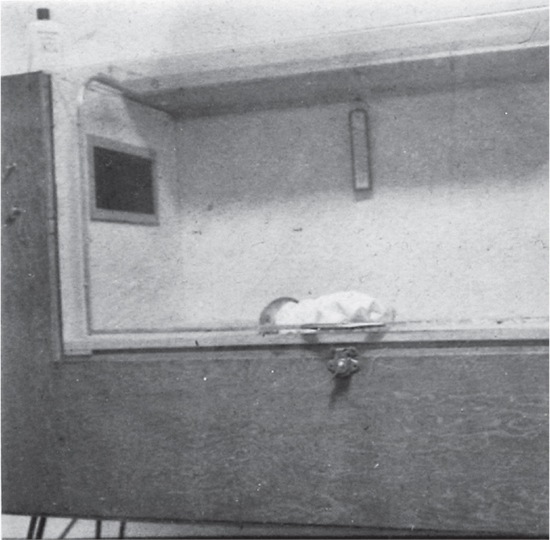

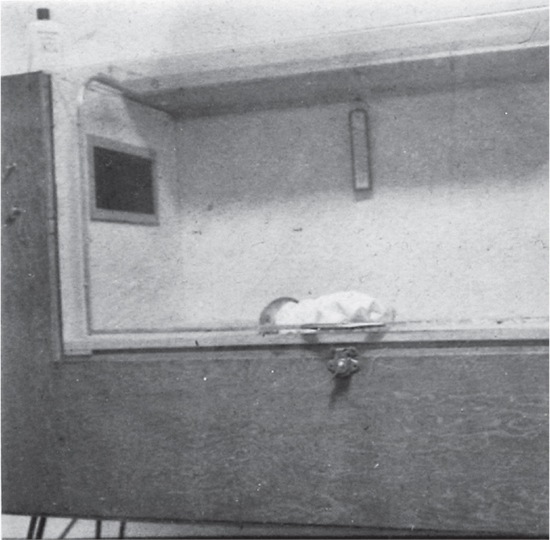

Figure P.1. The author in a Skinner box made by Ben Wykoff, an early teaching machine pioneer, 1956.

Authors collection

My own childhood offers a unique perspective on learning machines. My experimental-psychologist father was a colleague of the behaviorist B. F. Skinner at Harvard University in the 1950s, and I grew up enmeshed in the small, hubris-filled world that was 1960s behaviorism. Like all dutiful children of that world, I spent my earliest months in a Skinner box, which, unlike the boxes Skinner used for pigeons, merely provided a comfortable environment for me to roll around in and, of course, bragging rights among my parents peers ().

My siblings and I sometimes worked in my fathers lab after school, earning a nickel for each programmed instruction card we made for the teaching machines he used in his research projects. Teaching and learning were common dinner topics, as was gossip about the leading behavioral researchers of the day, many of whom are portrayed in this book. In middle school, I learned geometry using a teaching machine (which took only half the time to master rather than taking the class in the traditional manner).

The behaviorists of that time believed they had cracked the secret of how people learn, by extending their ground-breaking work on animal learning in carefully controlled experiments. We have since found that human learning is a more complicated process than they initially conceived, but their influence, both positive and negative, has cast a long shadow on education in general, and on educational technology in particular.

How This Book Is Organized

The kinds of teaching machines explored in the chapters that follow are particular innovations framed in unique environments, but several common threads emerge from these individual stories to provide useful connections to a larger narrative. The gist of that narrative is that there has been a long history of people trying to use technology to facilitate education and that those efforts have consistently failed to live up to the promises of their promoters.

To parse out the reasons for these failures, I use the following lenses to explore each efforts history, influences, contexts, and impact in a narrative form, with the lives of the machines innovators as the foundation:

Personal. The lives and personal influences of the innovators themselves provide rich threads to weave with other factors and offer a fuller and more interesting story. As it turns out, the innovators were complicated, quirky, and fascinating people whose relationships and influences often interconnected.

Personal. The lives and personal influences of the innovators themselves provide rich threads to weave with other factors and offer a fuller and more interesting story. As it turns out, the innovators were complicated, quirky, and fascinating people whose relationships and influences often interconnected.

Historical. The historical context in which the machines were invented had a strong influence on why and how they were created, flourished, and ultimately failed.

Historical. The historical context in which the machines were invented had a strong influence on why and how they were created, flourished, and ultimately failed.

Theoretical. The theoretical consensus on how people teach and learn is constantly evolving, and teaching machines were often used as Trojan horses for various movements (particularly behaviorism), which had strong influences on their design, efficacy, and adoption.

Theoretical. The theoretical consensus on how people teach and learn is constantly evolving, and teaching machines were often used as Trojan horses for various movements (particularly behaviorism), which had strong influences on their design, efficacy, and adoption.

Economic and business. Machines of all kinds are employed because of a strong economic motivation to reduce costs through automation, and teaching machines are no exception. Many of the proponents of teaching machines actively pursued commercial interests surrounding their academic efforts.

Economic and business. Machines of all kinds are employed because of a strong economic motivation to reduce costs through automation, and teaching machines are no exception. Many of the proponents of teaching machines actively pursued commercial interests surrounding their academic efforts.

Political. Few fields are as political as education, particularly in K12. Teaching machines have been seen as both the great equalizer and the great divider along racial, socioeconomic/equity, and academic-ability lines. Some have viewed them as a means to disintermediate the role of teachers and even entire academic institutions.

Political. Few fields are as political as education, particularly in K12. Teaching machines have been seen as both the great equalizer and the great divider along racial, socioeconomic/equity, and academic-ability lines. Some have viewed them as a means to disintermediate the role of teachers and even entire academic institutions.

Next page

Personal. The lives and personal influences of the innovators themselves provide rich threads to weave with other factors and offer a fuller and more interesting story. As it turns out, the innovators were complicated, quirky, and fascinating people whose relationships and influences often interconnected.

Personal. The lives and personal influences of the innovators themselves provide rich threads to weave with other factors and offer a fuller and more interesting story. As it turns out, the innovators were complicated, quirky, and fascinating people whose relationships and influences often interconnected.