NO SETTLEMENT, NO CONQUEST

A History of the Coronado Entrada

RICHARD FLINT

University of New Mexico Press

Albuquerque

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8263-4364-2

2008 by the University of New Mexico Press

All rights reserved. Published 2008

Printed in the United States of America

First paperbound printing, 2013

Paperbound ISBN: 978-0-8263-4363-5

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Flint, Richard, 1946

No settlement, no conquest :

a history of the Coronado Entrada / Richard Flint.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8263-4362-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Coronado, Francisco Vsquez de, 15101554.

2. Southwest, NewDiscovery and explorationSpanish.

3. Southwest, NewHistoryTo 1848.

4. Indians of North AmericaSouthwest, NewHistory16th century.

5. Historic sitesSouthwest, New.

6. Excavations (Archaeology)Southwest, New.

7. Southwest, NewAntiquities.

8. Southwest, NewDiscovery and explorationSpanishSources.

I. Title.

E125.V3F58 2008

979'.01dc22

2007047694

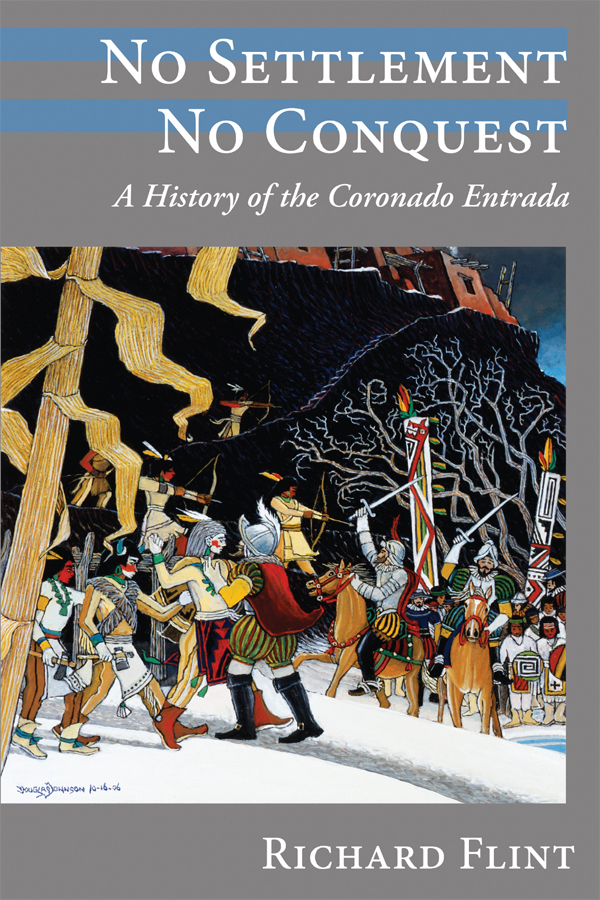

Cover painting: 1541Battle of Basalt Point Pueblo, gouache on paper, by Douglas Johnson.

With my utmost appreciation and affection to Carroll L. Riley and Brent Locke Riley

The only thing worth my writing or anyone's writing is a book that says, hey, this seems to have been left out of the picture.

BERNARD DEVOTO TO GARRETT MATTINGLY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ALTHOUGH MY NAME APPEARS as sole author of this book, and indeed I am responsible for its writing, much of the research on which it is based derives from projects undertaken during the past twenty-six years in partnership with Shirley Cushing Flint. Were she not currently at work on a book-length project of her own, this book would have been a more collaborative effort than it already is. Even so, it has benefited from her editorial scrutiny, without which it would be a different and impoverished product.

I also owe sincere appreciation to the members of the Santa Fe seminar, who read and commented on several chapters in the book. Thanks are due especially to Sandra Lauderdale Graham, Richard Graham, and Carroll Riley, who read the entire manuscript and offered many helpful suggestions. My particular gratitude goes to Suzanne Flint, who also read and commented on the entire text. I have often written with her in mind as a well-educated, non-historian reader. And I am grateful to John L. Kessell and David J. Weber for their continuing support and encouragement.

The dust jacket illustration is a painting by Douglas Johnson, who lives in Coyote, New Mexico, titled

1541The Battle of Basalt Point Pueblo. The subject of the painting is an encounter in early 1541 between Garca Lpez de Crdenas, the second

maestre de campo of the Coronado expedition, and three Pueblo men at the pueblo of Mohopossibly the ruin now known as Basalt Point Pueblo on Santa Ana Mesa, overlooking modern San Felipe Pueblo in New Mexico. After Lpez has been persuaded to leave his weapons behind, he and the Indians approach one another on foot, at least two of the Indians concealing clubs behind their backs. As the lead Indian embraces Lpez, the two others draw their clubs and beat him over the head. Immediately, several Spanish horsemen race from nearby to the

maestre de campo's aid, narrowly preventing his being dragged off to the pueblo and, presumably, killed. This incident is recounted in .

INTRODUCTION

The Mechanics of the Event

IN THE COURSE OF LITTLE MORE THAN A CENTURY, from 1492 to about 1600, armed parties from the Old World, aided crucially by large cohorts of Native American men, forcibly took control of many peoples of the vast twin continents that have come to be known as the Americas. Propelled by desire for status, honor, and wealth, energized by unquestioned certainty about the principles governing the natural and social worlds, expeditionaries fanned out over the southern two-thirds of the Western Hemisphere. Toward the middle of the sixteenth century the tide of conquest reached what is today northwestern Mexico and the American Southwest in the form of the Coronado expedition.

Between 1539 and 1542, that Spanish-led expedition of some 2,000 people, mostly Indians from what is now central and western Mexico, made an armed reconnaissance of a place they knew by the name Tierra Nueva. They intended to seize control of the people who lived there, in places called Cbola (SEEbohla), Marata (MahRAHtah), Totonteac (TohTOHNteyahc), Tiguex (TEEwesh), Tusayn (ToosighYAHN), and Quivira (KeeVEErah). In exchange for the local Indians surrender of control, they would offer to initiate the new vassals into the religion, economy, and way of life of sixteenth-century Spain. In return for such a priceless favor, the natives of Tierra Nueva were expected to accept and support don Francisco Vzquez de Coronado, captain general in the name of King Carlos I of Spain, as their overlord. All the nearly 400 European men who accompanied Vzquez de Coronado expected roles in running and sustaining the new Spanish provincia.

When the expedition reached Tierra Nueva, its resident peoples were exposed for the first time to the customs, beliefs, mores, and institutions of Europe and Africa. Interaction between Indians and Old World natives was not invariably confrontational, but on the whole, discord between the groups far outweighed the moments of congeniality. Fighting broke out often. Sullen stand-offs were the norm. People on both sides were killed and maimed, although American natives bore a disproportionate share of the casualties. Everyone suffered.

The promise of lucrative and prestigious colonial offices went unfulfilled. Most of the Europeans who survived the entrada, or armed reconnaissance, returned south to Nueva Espaa disillusioned and heavily in debt. They left behind in Tierra Nueva dislocation and destruction in most places where the expedition had spent more than a few days. As a result, suspicion and wariness, even hostility, characterized each group's perception of the other. The stage was set for further friction when next the two peoples would meet.

How the Coronado entrada was conducted and why it unfolded as it did; what the responses of the natives of Tierra Nueva were to the expedition and why they pursued the options they did; what effects the expedition had on its own members and the Indians it sought to control; how the events and outcomes of the expedition fit with those of similar, contemporaneous undertakingsI explore all these subjects in this book.

Drawing from documentary and archaeological sources, I develop a chain of explanatory narratives that account in significant part for the actions of people of the Coronado expedition and of the American natives they met at critical junctures during the expedition's course. To do that, I highlight selected words and actions of many members of the Coronado expedition and of indigenous persons, in order to understand why members of each group made certain choices and why those choices produced the outcomes they did. Although evidence relating to individual people fills this book, my main intent is to tell the aggregate story.

Albuquerque

Albuquerque