Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Invading Colombia : Spanish accounts of the Gonzalo

Jimenez de Quesada expedition of conquest / J. Michael

Francis [compilador].

p. cm.(Latin American originals ; 1)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-271-02936-8 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. ColombiaDiscovery and explorationSpanish.

2. ColombiaHistoryTo 1810Sources.

3. Jimnez de Quesada, Gonzalo, d. 1579.

I. Francis, J. Michael (John Michael). F2272.I58 2007

986.1dc22 2007033481

Copyright 2007

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by

The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 16802-1003

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. This book is printed on Natures Natural, containing 50% post-consumer waste, and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI z39.481992.

CONTENTS

This volume, LAO 1, Invading Colombia, along with LAO 2, Invading Guatemala, launch a new series of primary source texts on colonial and nineteenth-century Latin America. Latin American Originals (LAO) presents accessible, affordable editions of texts translated into Englishoften for the very first time. Some of the source texts were published in the colonial period in their original language (Spanish, Portuguese, or Latin), while others are archival documents written in Spanish or Portuguese or in indigenous languages such as Nahuatl, Zapotec, and Maya. The contributing authors are historians, anthropologists, art historians, and scholars of literature; they have developed a specialized knowledge that allows them to locate, translate, and present these texts in a way that contributes to scholars understanding of the period, while also making them readable for students and nonspecialists.

J. Michael Francis is one such author. He received his doctorate from the University of Cambridge in 1998 and has since taught Latin American history at the University of North Florida, where he is an associate professor, while continuing to study and publish on the history of the sixteenth-century New Kingdom of Granada (todays Colombia). In the course of doing research in the Spanish imperial archives in Seville, Francis uncovered a treasure trove of documents written by Spaniards who had survived their invasion of Colombia in the 1530s. These sources allowed him to construct a narrative of the invasion told by multiple witnesses. Almost none of the documents have been published before, and none have ever been published in English.

If that fact alone does not make this volume a majorand fascinatingcontribution to the history of conquest and colonization in the Americas, two other aspects of the story are equally striking. First, the early part of the narrative eerily echoes the story of Francisco Pizarros invasion of the Inca Empire just a few years before; and yet, second, that tale is famous, and this one almost completely unknown. Why this vast discrepancy? And which invasion was more typical of the Spanish experiences of the era? Why did the young lawyer-conquistador Gonzalo Jimnez de Quesada, who led more Spaniards into Colombia than Hernando Corts led into Mexico or Pizarro into Peru, fail to go down in the history books alongside those two legendary compatriots of his? Is it possible that the well-known invasions that brought down empires tell us less about the Spanish Conquestand are in the end less interesting than disastrous invasions such as Jimnez de Quesadas? I think the answer may be yes, and I invite the reader to ponder the question as the narrative presented below unfolds in all its glorious, grim detail.

Matthew Restall

A great many soldiers walked barefoot, blood spilling from the open wounds on their feet; and many died from hunger because we found few settlements from which to gather enough provisions for such a large group. And thus the men died, ten at a time; others simply were left behind [to die] along the way. Still others, while resting in their hammocks, were snatched by tigers. And some soldiers who ventured down to the Ro Grande to gather [water], were ripped to pieces and eaten by caimans, while the [other] soldiers [stood by], helpless to save them.

The storyline follows a familiar plot. It is the third decade of the sixteenth century, and a small band of Spanish adventurers, fewer than two hundred in all, climb the western flank of the South American Andes. They have timed their arrival well; the local indigenous population is divided, engaged in a bitter civil war between two rival factions. The conflict not only allows the Spaniards to exploit these deep political divisions, it also prevents any unified defense against the newcomers, who quickly plot their strategy. In accordance with long-established military procedure in the Americas, the Spaniards seize the powerful ruler and place him under house arrest. To secure his safe release, the captive leader makes a tantalizing offer. In exchange for his freedom, he offers to fill an entire room with a treasure of precious metals and gemstones. The Spaniards accept. To this point in the story, despite the overwhelming numerical superiority of indigenous forces, not a single Spaniard has lost his life in combat. The native ruler is not so fortunate.

Despite the obvious similarities, the preceding paragraph does not describe the opening phase of the Spanish conquest of Peru.

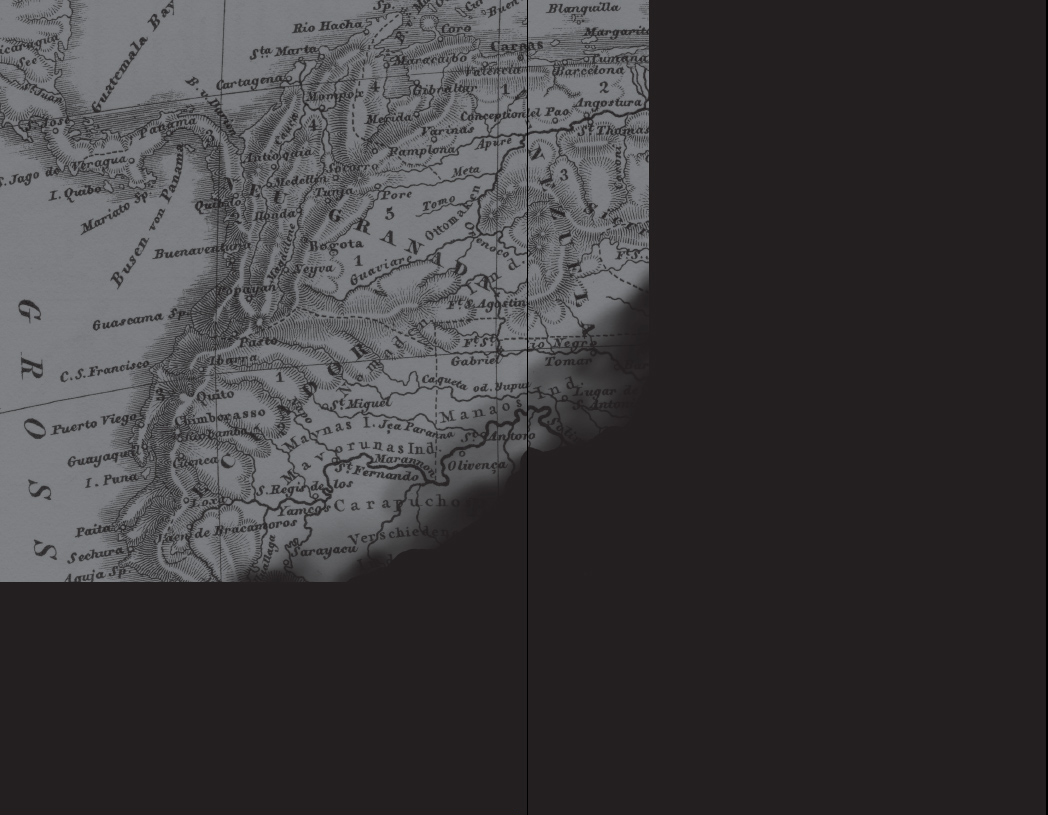

In early April 1536, a twenty-seven-year-old lawyer named Gonzalo Jimnez de Quesada led a military expedition from the coastal city of Santa Marta deep into the interior of what is today modern Colombia. With roughly eight hundred Spaniards and an undetermined number of native carriers and black slaves, the Jimnez expedition was larger than the combined forces under Hernando Corts in Mexico and Francisco Pizarro in Peru. Jimnezs men were divided into two separate groups, with five to six hundred Spaniards marching overland, supported by more than two hundred others who boarded five brigantines and sailed up the Magdalena River. The official purpose of the expedition was twofold: to find an overland route from Colombias Caribbean coast to newly conquered Peru, and to follow the Magdalena River to discover its source, which some believed would lead the expedition to the South Sea (the Pacific Ocean). It found neither. Instead, nearly three-quarters of Jimnezs men perished, most from illness, hunger, and malnutrition. Some Spaniards fell victim to jaguar or cayman attacks, or to mortal wounds from native arrows laced with the deadly twenty-four-hour poison. Others, too exhausted or injured to continue, limped back to the brigantines and returned to Santa Marta. Yet, despite the high casualty rate, for the 179 survivors of the twelve-month venture, the expedition proved to be one of the most profitable campaigns of the sixteenth century. In early March 1537, almost a full year after they had set out from Santa Marta, Jimnez and his men successfully crossed the Opn Mountains and reached the densely populated and fertile plains of Colombias eastern highlands, home to the Muisca.

Jimnez and his men recognized immediately the importance of their discovery. The dense population, rich agricultural lands, pleasant climate, splendid public architecture, and, perhaps most important, evidence of nearby sources of gold and emeralds, were unlike anything they had seen elsewhere in the province of Santa Marta. But instead of returning to the coast to report their discovery to the man who had organized and funded the expedition, Santa Martas governor, don Pedro Fernndez de Lugo, Jimnez and his followers decided to delay their return. Perhaps they did not want to risk losing the spoils of their hard labor and suffering to the many newcomers who would flood the region upon hearing news of its riches. Over the next two years, and without contact or correspondence with any other Europeans, the entire expedition remained in Muisca territory. From roaming base camps, they circulated throughout the eastern highlands, driven by their quest to uncover the regions riches and collect booty. They even ventured far outside the Muisca realm to investigate rumors of gold-filled palaces and mysterious tribes of Amazon women. They formed alliances with some Muisca leaders, fought against others, and participated in joint military campaigns against the Muiscas fiercest enemies, the Panches. Remarkably, only six Spaniards died during the expeditions first thirteen months in Muisca territory, and none as a result of military conflict.