ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express appreciation to persons who have helped at various stages and in different ways in the period of planning, executing, and publishing this research. Professor Donald Matthews of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill provided an initial word of encouragement after reviewing the proposal and outline. Eddie Lincoln, Bronah Miller, and Mrs. Emily Lincoln assisted during the research and writing stages by competently fulfilling assignments with unusual enthusiasm. The offices of the Secretary of State and the State Board of Elections were always prompt and helpful in responding to my requests for election data and information. The university and departmental administrations at Wake Forest provided a teaching schedule that accommodated work on the manuscript. The Graduate Council, through its Research and Publication Fund, granted financial assistance. Others made contributions for which I am grateful.

A constant source of encouragement and assistance was my wife, Martha, who contributed in ways too numerous to mention. In conjunction with my two children, John Charles and Katherine Stuart, she provided a home environment which made research possible and enjoyable.

None of these persons is responsible for errors in the book. If any reader finds errors, I hope he will be kind enough to inform me of them. Suggestions for improvement of the scope and content of the book are also welcomed.

INTRODUCTION

The North Carolina Constitution states in Article I:

That all political power is vested in, and derived from, the people; all government of right originates from the people, is founded upon their will only, and is instituted solely for the good of the whole.

Thus, the fundamental law of the state creates a republican form of government in which government is based on popular sovereignty and is composed of representative institutions. The existence of republican and democratic government is guaranteed for every state by the United States Constitution.

In order to secure this objective of democratic republican government many institutions and arrangements have been devised. Voting rights have been determined, political parties created and recognized, and campaigns waged and regulated to provide the instruments and means of popular control. The focus of this book is the politics of North Carolina since 1940. A better knowledge of the structure and nature of competition for popular control and representative government is the main objective. This objective is achieved by examining major features of the states electoral system in the last quarter century.

The knowledge of politics in North Carolina is not only useful to the professional students of politics: political scientists and politicians. Knowledge and understanding of the foundations of political power are critical to individual citizens for two reasons. On them the citizen can base a more enlightened participation in the political system. Equally important, the citizens can determine the degree to which and the manner in which the constitutional principle of popular government is achieved.

The Political Terrain

Politics occurs in and develops from a social, economic, and political context that is not easily identified and readily apparent. Political issues arise from a variety of seemingly nonpolitical characteristics of the state such as the age of the population, the ethnic composition, the level of education, the type of economic bases, the level of personal and corporate income, and others. Basic patterns of party competition are influenced by the division of governmental authority, the public offices that are provided, the methods of selecting people to fill these offices, and the boundaries of jurisdiction of these offices.

Politics revolves around elected offices that are established for certain constituencies. Political constituencies range in size and jurisdiction from the state to the local ward. The state serves as the political district for the executive officials, which includes the governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and seven members of the council of state (auditor; commissioners of agriculture, insurance, and labor; secretary of state; superintendent of public instruction; and treasurer). These ten officers are elected directly by the voters. There are no state legislative officials who are elected with the state as their constituencies. Members of the judicial branch, including justices of the Supreme Court and judges of the Court of Appeals and Superior Courts, are elected on a statewide basis. The states two United States senators and its presidential electors are elected on a statewide basis.

The General Assembly, 120 members in the House of Representatives and 50 in the Senate, is elected from districts which the Assembly determines. Until 1966 the districts of the state House of Representatives were the 100 counties. According to the state Constitution written in 1868, each county was allotted one member in the lower house. An additional 20 representatives were apportioned to the counties on the basis of population. In 1964 the United States Supreme Court ruled in Reynolds v. Sims that representation in both houses of a state legislature must be based on population that is substantially equal. By 1966 the impact of this decision was felt in North Carolina, and the 300-year-old pattern of separate legislative representation for each county was abandoned.

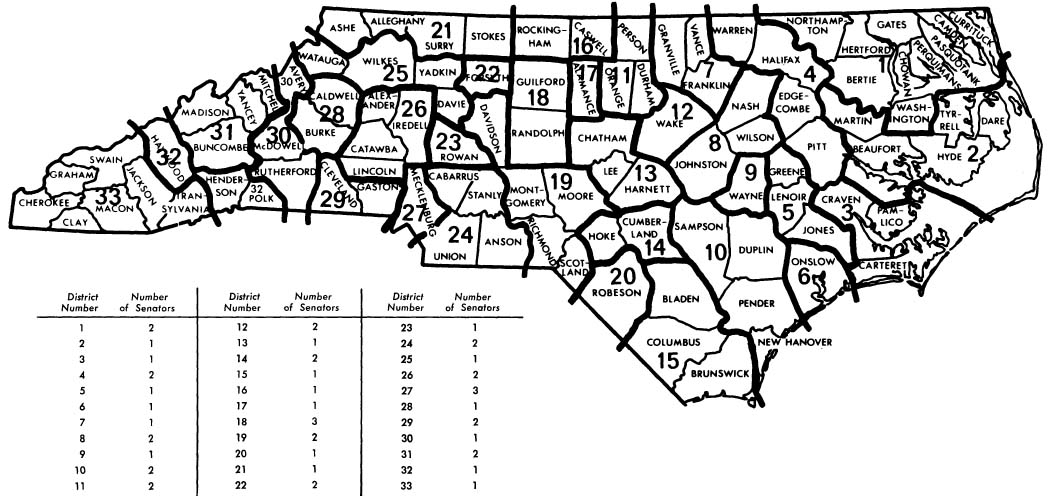

The state Constitution gives the legislature the authority to determine Senate districts, but it sets forth two important provisions. The districts are to be revised after every decennial census and are to be, as nearly as possible, based on equal population. The state legislature took a casual attitude toward both of these provisions. The Senate districts redrawn in 1963 had last been revised in 1941, and in 1961 the House was reapportioned for the first time since that year. Both Senate redistricting and House reapportionment were inconsistent with the Reynolds decision of the Supreme Court. Thus action taken by the General Assembly in special session in 1966 determined the present districts for both houses of the state legislature. Figures I and II show these districts of the House and Senate.

Figure I. STATE SENATE DISTRICTS , 1966

Figure II. STATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICTS , 1966

The 120 seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned among 49 districts composed of 1 to 6 counties each. Districts have from 1 to 7 representatives, and they range in population per member from 43,444 to 32,660 with an average of 37,968. The reapportionment and redistricting of this house contrast dramatically with what existed before. Two measures that emphasize this are population variance ratiocomparison of largest and smallest population per memberand minimum controlling percentagethe smallest percentage of people required to elect a majority of the body. Before the 1966 plan the population ratio varied 18.15 to 1; after the special session the ratio was 1.33 to 1. Prior to 1966, 27.09 per cent of the population could elect 61 members of the house; after the change, the figure was 47.54 per cent.