Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

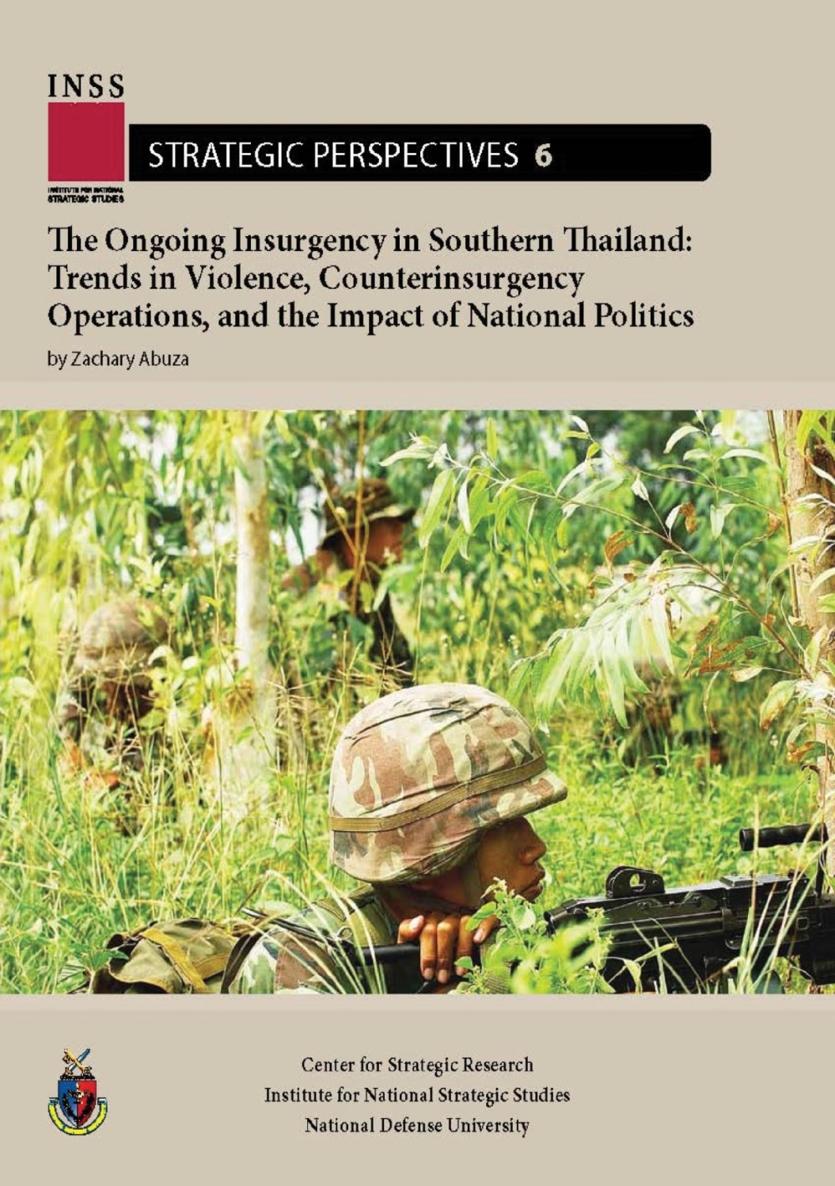

THE ONGOING INSURGENCY IN SOUTHERN THAILAND:

TRENDS IN VIOLENCE, COUNTERINSURGENCY OPERATIONS, AND THE IMPACT OF NATIONAL POLITICS

BY

ZACHARY ABUZA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Institute for National Strategic StudiesNational Defense University

The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense Universitys (NDUs) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, Center for Complex Operations, and Center for Strategic Conferencing. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, and publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach.

The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Unified Combatant Commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community.

Executive Summary

Since January 2004, a Malay-Muslimbased insurgency has engulfed the three southernmost provinces in Thailand. More than 4,500 people have been lulled and over 9,000 wounded, making it the most lethal conflict in Southeast Asia. Now in its 8 th year, the insurgency has settled into a low-level stalemate. Violence is down significantly from its mid-2007 peak, but it has been steadily climbing since 2008. On average, 32 people are being killed and 58 wounded every month. Most casualties are from drive by shootings, but there are also about 12 improvised explosive device (IED) attacks a month.

The insurgency is now characterized by less indiscriminate violence and more retaliatory attacks. Insurgents continue to target security forces, government officials, and Muslim moderates who seek accommodation with the Thai state as part of efforts to make the region ungovernable by limiting provision of social services and driving Buddhists from the south. The overall level of violence may be influenced more by insurgent calculations about the optimum amount of violence needed to advance their political goats than by improved capabilities of the security forces.

Despite better coordination, Thai counterinsurgency operations are still hampered by bureaucratic infighting and a lack of professionalism. Human rights abuses by security services with blanket immunity under the Emergency Decree continue to instill mistrust among the local population. Moreover, as long as violence is contained in the deep south, the insurgency will remain a low priority for the new Thai government, which is focused on national political disputes and is reluctant to take on the military by pursuing more conciliatory policies toward the south. Indeed, even under the 30-month tenure of the Democrat Party with an electoral base in the south, the insurgency was a very low priority and its few policy initiatives were insufficient to quell the violence.

The new Pheu Thai government under Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra, the younger sister of Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted in a September 2006 coup, will have its hands tied in the south. Its election victory and focus on national reconciliation have already engendered mistrust of the Thai military. The new government will be reluctant to criticize the militarys handling of the insurgency, take on the culture of impunity or push for any form of political autonomy. This will make any devolution of political authority unlikely, limiting chances for a negotiated solution. As a result, low level violence is likely to continue indefinitely.

The most important immediate U.S. objective in Thailand is political stability at the national level and deepening bilateral economic ties. Absent a cohesive Thai government with the political will to overcome military resistance to policies that might address underlying causes of the insurgency, U.S. pressure to do more is likely to be ineffective or even counterproductive. Accordingly, the United States should maintain quiet diplomatic pressure on the government to broaden its counterinsurgency efforts and offer any requested intelligence and law enforcement assistance, while being cognizant of Thai sensitivity over its sovereignty.

Introduction

The national elections that took place on July 3, 2011, are unlikely to resolve the intense political polarization that has wracked Thailand since 2006, when Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra was ousted in a military coup. Since then, there have been six prime ministers and a series of weak coalition governments that the military has manipulated easily. The elections are also unlikely to lead to any progress in the long-simmering insurgency in the countrys three Muslim majority provinces in the deep south. Indeed, the electoral campaign in the Bangkok-centric nation focused on elite politics, the growing rift between the urban middle class and rural constituents, and the future role of the exiled Thaksin. What was glaringly absent was any serious discussion of the insurgency. The two main parties, the incumbent Democrat Party and opposition Pheu Thai Party, both asserted that they would do better at resolving the insurgency than their rival, but neither party outlined any new initiatives or concrete policies.

The Malay-based insurgency in three southern Thai provinces, Yala, Pattani, and Narathiwat, and parts of a fourth, Songkhla, re-erupted in January 2004 and is now in the middle of its 8 th year. Roughly 80 percent of the 1.7 million people in these provinces are Muslims and Melayu speakers. The insurgency has claimed the lives of more than 4,500 people and wounded nearly twice that number in some 11,000 incidents of violence and over 2,000 bombings. In the process, the insurgency destroyed much of the social fabric of southern Thailand, particularly in the countryside. {1} Some 20 percent of the minority Buddhist population has abandoned its land, either fleeing the south altogether or moving into the relatively safe towns. The decentralized and madrassa-based insurgency has confounded the Royal Thai Army (RTA) and other security forces, which have been unable to gain the initiative. Despite 60,000 security forces, Thai baht (THB) 145 billion ($4.9 billion) in expenditures, and the arrest of thousands of alleged insurgents, the violence has continued unabated. There are no signs that the insurgency is actually being defeated. The only country with more IED attacks is Afghanistan.