This book was published with the assistance of the Thornton H. Brooks Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2015 Kenneth Robert Janken

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Set in Miller by codeMantra, Inc.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

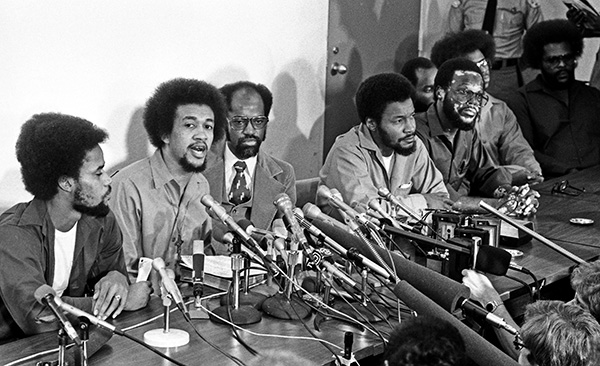

Jacket illustration: Wilmington Ten press conference, News and Observer, 24 January 1978. Used by permission of the News and Observer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Janken, Kenneth Robert, 1956 author.

The Wilmington Ten : violence, injustice, and the rise of black politics in the 1970s / Kenneth Robert Janken.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2483-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-2484-6 (ebook)

1. RiotsNorth CarolinaWilmingtonHistory. 2. African AmericansNorth CarolinaWilmingtonHistory. 3. Wilmington (N.C.)Race relations. 4. Wilmington (N.C.)History. I. Title.

F264.W7J36 2015

305.800975627dc23

2015022646

Parts of several chapters appeared as Remembering the Wilmington Ten: African American Politics and Judicial Misconduct in the 1970s, North Carolina Historical Review 92 (January 2015): 148.

Illustrations and Maps

ILLUSTRATIONS

Boycott committee at a press conference at Gregory Congregational Church,

Schwartzs Furniture,

Student demonstration in front of city hall on 5 February,

Mikes Grocery burning,

North Carolina National Guard in front of Gregory Congregational Church,

Allen Hall in handcuffs,

Prosecutor Jay Strouds list of advantages and disadvantages of a mistrial,

Page 1 of Jay Strouds jury selection notes,

Free the Wilmington 10 poster,

Wilmington Ten press conference at Central Prison in Raleigh,

Protest in Raleigh in April 1978,

Singing and chanting protesters in April 1978,

MAPS

1. Clustering of incidents of shootings and firebombings related to the Wilmington school boycott,

2. Location of shootings and firebombings related to the Wilmington school boycott,

Introduction

Wilmington and the 1898 Mentality

The case of the Wilmington Ten amounts to one of the most egregious instances of injustice and political repression from the postWorld War II black freedom struggle. It took legions of people working over the course of the 1970s to right the wrong. Like the political killings of George Jackson and Fred Hampton, the legal frame-up of Angela Davis, and the suppression of the Attica Prison rebellion, the Wilmington Ten was a high-profile attempt by federal and North Carolina authorities to stanch the increasingly radical African American freedom movement. The facts of the callous, corrupt, and abusive prosecution of the Wilmington Ten have lost none of their power to shock more than forty years after the fact, even given todays epidemic of prosecutorial misconduct. Less understood but just as important, the efforts to free the Wilmington Ten helped define an important moment in African American politics, in which an increasingly variegated movement coordinated its efforts under the leadership of a vital radical Left.

In the first week of February 1971, African American high school students in the newly desegregated school system in Wilmington, North Carolina, staged a school boycott to protest systematic mistreatment by the citys education authorities, teachers, police who were called to campus, and white adult thugs who harassed them on school grounds. The students issued a list of demands and established a boycott headquarters at a church in town.

As news of the boycott was disseminated through the local media, the homegrown paramilitary Rights of White People (ROWP) organization launched violent attacks on the church and the students gathered there. Enduring drive-by shootings and receiving no police protection, the boycotters and their supporters fought back, establishing an armed guard around the churchs perimeter. Some supporters, to this day unknown, burned a number of nearby white-owned businesses, including a mom-and-pop store called Mikes Grocery close to the church. (In the chaos, other instances of arson apparently were committed by business owners eager to collect insurance money.) At the same time Mikes was going up in flames, police shot and killed a student leader who many claim was unarmed. The next morning, an armed white vigilante was shot and killed as he prepared to attack the church.

While city officials had greeted the massive violence against blacks with a yawning indifference, the death of a white provocateur-cum-terrorist stimulated a swift response. Wilmingtons mayor finally declared a curfew and the governor mobilized the National Guard, which raided and took control of the boycott headquarters. The authorities show of force reduced the level of violence in the city, but what calm did return felt sullen, as none of the black students and parents grievances had been addressed.

After the rebellion was suppressed, local white officials and the press called the police to task for not being aggressive enough against the boycott. One judge stated from the bench that he would have treated protesters as Lieutenant William Calley had treated the villagers of My Lai. The daily newspaper called protesters hoodlums. There were a few letters to the editor from sympathetic whites who counseled understanding, but the loudest voices issued full-throated howls for retribution.

A year later, in March 1972, smarting still from the uprising and wishing to exact payment for it, local and state authorities arrested seventeen persons on charges related to the week of violenceall of them involved with the protest, none from the ROWP. In September 1972, ten of themthe Wilmington Tenwere put on trial for burning Mikes and conspiring to shoot at the police and firefighters who responded to the blaze. (An eleventh person, George Kirby, was to have been tried with the others, but he jumped bail and the trial proceeded without him.) During the trial, the judge bulldozed the defense, and the prosecutor produced witnesses who he knew would implicate the Ten by lying. With the judges active assent, the prosecutor illegally excluded most blacks from the jury. Given the legal machinations, after a few hours of deliberation the Wilmington Ten, not surprisingly, were convicted on all counts and sentenced to a total of more than 280 years in prison.

In short order a widespread and worldwide campaign arose to free them. Powered by the grassroots organizing of black nationalist organizations, it came to include adherents of other political ideologies, elected officials, elite public opinion makers, foreign governments, and Amnesty International, which designated the Wilmington Ten prisoners of conscience. In December 1980, faced with both a mobilized domestic and international public outcry and overwhelming evidence of judicial and prosecutorial misconduct, a federal appellate court overturned the convictions.

Connie Tindall, Willie Earl Vereen, and Joe Wrightwas outrageous, but in its repression and resistance it was not singular. In Wilmington, the Port City, the modern traditions of spasms of violence, repression, and racial progress had been braided together since the late nineteenth century. And in the modern black freedom struggle of the 1960s and 1970s, the doggedness with which the authorities persecuted the Wilmington Ten was replicated in other places in cases with numbers attached: the Panther Twenty-One, the Charlotte Three, the Ayden Eleven, the Greensboro/Communist Workers Party Five.