Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

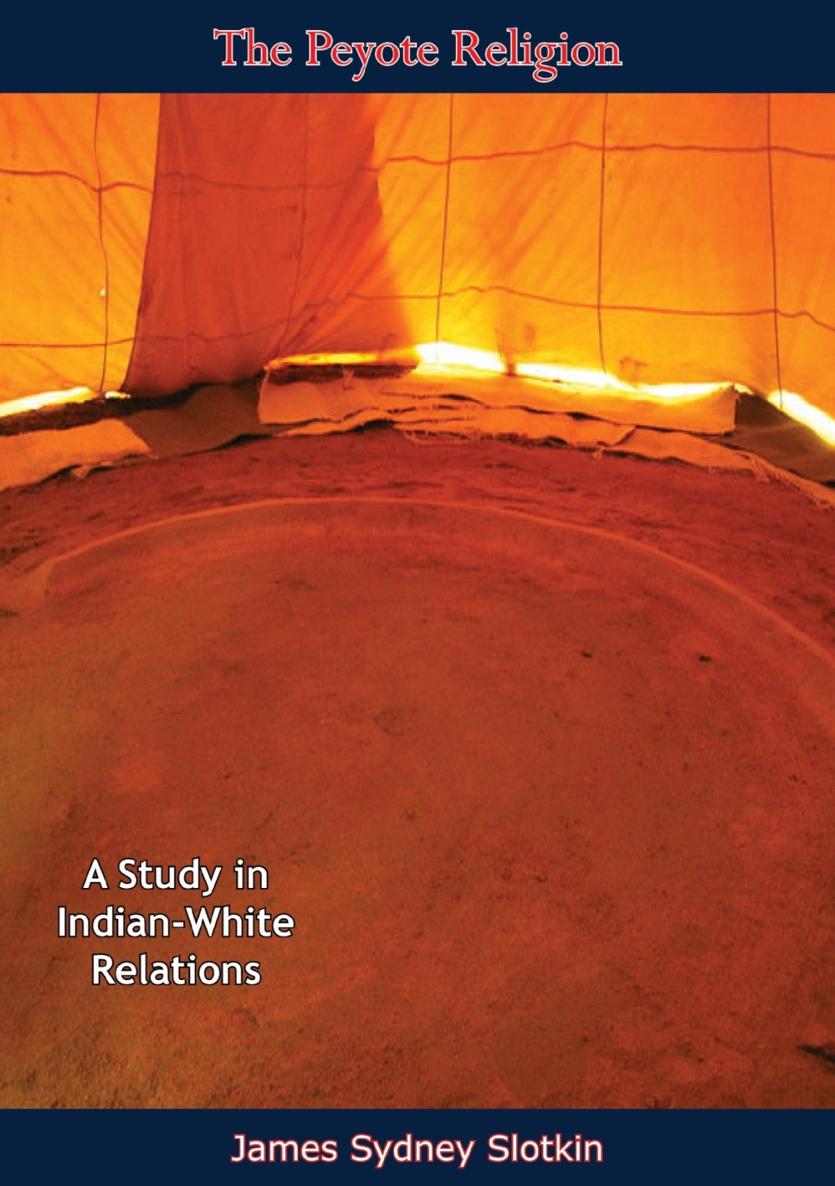

THE PEYOTE RELIGION

A STUDY IN INDIAN-WHITE RELATIONS

BY

J. S. SLOTKIN

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

PREFACE

The character of this work has depended upon the special circumstances under which it was undertaken, so that a statement on the matter seems appropriate.

When I finished my study on the early history of Peyotism, {1} and went away for a vacation in the summer of 1954, I thought I had completed all the research I would ever do on the subject. But on my return I found that during my absence two things had happened: I had been elected one of the Menomini delegates to the intertribal conference of the Native American Church of North America, and at that conference I had been elected an official of the Church.

I then felt obligated to continue my research on Peyotism, for the sake of both Peyotism and anthropology.

As far as the Peyotists who had elected me were concerned, I thought I owed it to them to put my anthropological training at their disposal. After some thought I suggested, and the other officers agreed, that a useful contribution would be a scientific presentation for Whites of the history and nature of Peyotism. So far no Peyotist has written extensively on his religion, and those who have written extensively have not been Peyotists. Therefore one purpose of this work is to present a documented exposition of Peyotism for Whites, from the Peyotist point of view.

As far as the anthropologists were concerned, I thought I owed it to them to make professional use of my unique position. To my knowledge, never before has a student of nativistic movements obtained a comparable place in such a group. My role as official permitted me to establish rapport, and thus to obtain data, different from that available to other scientists. Therefore I decided a useful contribution would be an historical and descriptive study of Peyotism as a nativistic movement. Previously I had made a descriptive study of Peyotism; {2} therefore in the present work I have concentrated on the historical approach. In this regard I have tried to make it a case study in ethno-historical method.

My original plan was for an elaborate project, but no foundation was interested in financing it. So the plan was revised to modest proportions which could be completed within a year by one person working part time. Because of these limitations the study is exploratory rather than definitive.

A few technical details should be mentioned. Tribes have been normalized according to Murdock; {3} the culture areas usually have been taken from Kroeber. {4} The bibliography on Peyotism is as exhaustive as I could make it, but far from complete. References to works in the bibliography are given in the abbreviated form customary among American anthropologists; other references follow usual conventions.

Next it is my pleasure to acknowledge the assistance I have received in the course of the study. All the officials in the Native American Church of North America have helped; particularly gratifying has been the assistance given by the president and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Allen P. Dale; and the secretary and her husband, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Williams. The anthropologists Donald Collier, Fred Eggan, Weston La Barre, Nancy Oestreich Lurie, W. C. McKern, Robert E. Ritzenthaler, and Omer C. Stewart generously supplied me with their unpublished material. Matthew J. Long located most of the documents in the National Archives; Mrs. Rella Looney, those in the Oklahoma Historical Society. Chauncy D. Harris, Dean of the Social Sciences at the University of Chicago, gave me an emergency grant to initiate the project begun so suddenly and unexpectedly; the study was completed by a grant from the Social Science Research Committee of the University of Chicago. My wife, Elizabeth J. Slotkin, assisted in the fieldwork and writeup. Publication has been financed by Sol Tax, Chairman of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Chicago.

IA THEORY OF NATIONALISM

This monograph deals with the ethno-history of Peyotism. Since all historical analyses are based upon generalizations about relevant processes, I shall try to make mine explicit at the outset. In the main, my theory is based upon the work of two sociologists: Parks race relations theory and Wirths nationalism theory. But I have found it necessary to modify their generalizations in order to fit the comparative data which are the concern of anthropologists. Consequently, it seems appropriate to begin with a summary of the theory which will be used to analyze Indian-White relations in general and Peyotism in particular. {5}

A crucial concept used in the theory is that of an ethnic group. An ethnic group is a population categorized as being racially and/or culturally distinct. It is so categorized by other people, by itself, or by both. Ethnic groups have their origin in social and cultural differences, and this leads us to a consideration of some phenomena resulting from the interaction between different societies and cultures.

When various societies, each with its own culture, come in contact, social and cultural interaction occur. Such interaction can vary in intensity. Minimum direct interaction takes the form of distant (i.e., rare and brief) social interaction with very few members of another society, and the diffusion of a few customs or artifacts from the latters culture. An example is the Western explorer who visits an isolated Indian tribe in western Brazil, and leaves some steel knives which are kept and used by the Indians. Maximum direct interaction takes the form of intersocialization and acculturation. Inter socialization is direct and close (i.e., frequent and lengthy) social interaction between a substantial proportion of the members of different societies. Acculturation is diffusion of many customs resulting from direct and close social interaction between a substantial proportion of the participants in different cultures. An example is the interaction between the Massachuset Indians and English settlers in Massachusetts during the 17 th century, when they lived in adjacent or the same communities, learned each others customs, and adopted each others artifacts.

Intersocialization may be harmonious or opposed. There is harmony (i.e., cooperation or collaboration) when the societies depend upon one another to achieve their goals. A case in point is the harmony between Reindeer Tungus and Russian Cossacks of northwestern Manchuria, who are mutually dependent for important trade items. {6} There is opposition (i.e., competition or conflict) when one or both societies expect to exclude, or be excluded by, the other society from the goals they are trying to achieve. This is illustrated by the opposition over Jerusalem between Moslems and Westerners during the Crusades. Particularly relevant for our study is the special case of opposition resulting from the attempt to establish a domination-subordination relation between the societies. It seems that two conditions are necessary for this kind of opposition to arise: (a) at least one of the cultures must include customs which incite to domination over other societies; (b) the society possessing this inciting trait must have the power to coerce the other societies. For instance, the early British and Americans in Hawaii, who had their usual cultural incentives for domination, did not have the power to achieve it, and opposition did not occur between them and the Hawaiians.