E ver since Populuxe was published twenty-one years ago, fans of that book, editors, and friends have been asking me when I was going to do a follow-up.

Barney Karpfinger, my agent then and now, deserves my thanks for two reasons. He stopped me from doing so until we were both sure that what I had to offer was a statement in itself, not just a sequel. And when the time came, he worked effectively to make it happen.

Iris Weinstein, who designed Populuxe and probably should have known better than to get into another messy project, has once again used typefaces, proportions, and telling details to make the book into a compelling artifact. As the author of a work on packaging, I know that books are judged by their covers, so I give thanks to Susan Mitchell, who designed this one.

Sarah Crichton is an extraordinary editor. After working with me closely to sharpen the text, she then drew on her magazine-editor past to challenge me to find fresh and memorable images that tell a story of their own. Like the period the book discusses, this was a project that seemed often on the verge of flying apart into countless little pieces. Assistant editor Rose Lichter-Marck managed to keep it pulled together, and Stacey Linnartz did a heroic job of getting everything finished. FSGs managing editor, Debra Helfand, and design director, Abby Kagan, helped support and nurture this difficult and atypical project.

Special thanks go to those who created the images used in this book. There are eleven photographs by Allan Tannenbaum, whose work provides the essential visual chronicle of New York nightlife and culture during this period, and five by Peter Simon, whose work provides an essential, Arcadian counterpoint. Photographs taken for the old Philadelphia Evening and Sunday Bulletin form the core of the Temple University Urban Archive, from which I have drawn many images. I spent the decade working for The Philadelphia Inquirer, the competition, but I am grateful for the professionalism and creativity of the Bulletins photographers, to Temple for keeping and cataloguing the material, and to the archivist John Pettit. I have also drawn on the enormous wealth of photos, documenting everything from urban street styles and houses made out of beer cans to inaugural balls and moon missions, made for various federal agencies and available to all through the National Archives. Several people went out of their way to find images for the book and get them in printable form. These include Rick Stroud of the International Association of Administrative Professionals, Megan Moholt of the Weyerhaeuser Company, Stephen Grande of the Houston Astros, Earle Barnhart of the Green Center, Chip Lord of Ant Farm, Dwayne Cox of Auburn University, Ilona D. Williamson, Dorothy Delina Porter, Howard Gribble, Steven Stengel, Paul W. Drew, Charlotte Strick, Jeff Williams, and Bob Lash (whose recollections of the Homebrew Computer Club can be found at www.bambi.net/bob/homebrew.html ).

David G. De Long, Jim Shulman, Jim Ashbrook, and Howard S. Shapiro all read the completed manuscript and made suggestions that improved the book. Thanks go also to Arlene Love and Robert lorillo, who shared their collections of seventies imagery, and to countless others who shared memories of their Great Funkera wardrobes, homes, and consciousness.

I Want That!: How We All Became Shoppers

The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager

The Total Package: The Secret History and Hidden Meanings of Boxes,

Bottles, Cans, and Other Persuasive Containers

Facing Tomorrow: What the Future Has Been,

What the Future Can Be

Populuxe

Thomas Hine is the author of five previous books on American culture and design, including Populuxe , The Total Package , and The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager. He writes frequently for national and regional magazines and newspapers. He has also served as an adviser or consulting curator for museum exhibitions in Los Angeles, New York, Denver, and Miami. He was architecture and design critic for The Philadelphia Inquirer from 1973 to 1996. He lives in Philadelphia.

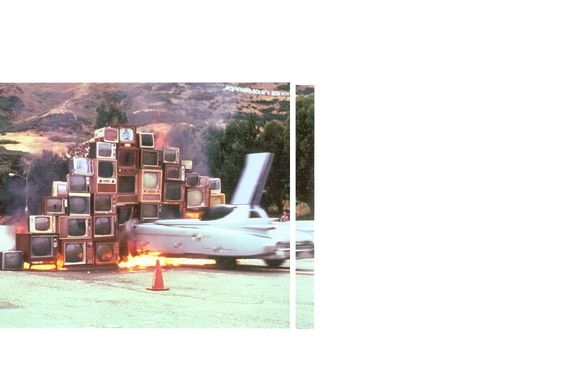

Courtesy of Ant Farm, photo by John F. Turner.

I f you wanted a world that was orderly, where progress was guaranteed, the seventies were a terrible time to be alive. Cars were running out of gas. The country was running out of promise. A president was run out of office. And American troops were running out of Vietnam.

Only a decade before, as the nation anticipated the conquest of space, the defeat of poverty, an end to racism, and a society where people moved faster and felt better than they ever had before, it seemed that there was nothing America couldnt do. Even the protestors of the sixties objected that America was using its immense wealth and power to do the wrong things, not that it did things wrong. Yet during the seventies it seemed that the United States couldnt do anything right. The country had fallen into the Great Funk.

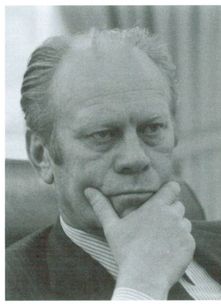

America even fumbled the celebration of its birthday. In 1975, the United States began a multiyear observance of the two-hundredth anniversary of the American Revolution. Fifteen years earlier, such a celebration would have engaged America, but by the mid-seventies, everything seemed to be falling apart. Four years of pageantry, featuring musket-wielding guys in tricorn hats, didnt feel like a solution for the countrys malaise. At many of the commemorations, Gerald Ford, that unelected, unexpected president, said some little-noted words. Ford presided over bicentennial America like a substitute teacher, trying to calm a chaos he had no hand in making and seemed scarcely to understand.

The bicentennial celebration left few memories, few images or events that have resonated through the decades since. Media Burn, staged on July 4, 1975, at San Franciscos Cow Palace, is an exception. It was not an official commemoration but rather a project of Ant Farm, an art and architecture collaborative. President Ford was not in attendance as he was at most of the bicens big moments. Instead, the presiding figure was an imitator of the late President John F. Kennedy, who was remembered at the time as the last real president, or at least the last who didnt leave office in disgrace. Havent you ever wanted to put your foot through your television? the ersatz Kennedy asked. In the climactic moment of the event, a specially modified and apparently driverless 1959 Cadillac Eldorado convertible crashed through a wall of vintage television sets. In fact, there was a driver hidden inside the car. And the crash was documented by a camera housed in an additional tail fin, constructed for the purpose.

An Eldorado hits the Zeniths as part of Ant Farms Media Burn, an unofficial bicentennial pageant that dramatized the seventies smashed expectations. Gerald Ford, an unexpected president, watched over the nations birthday in the wake of the sordid revelations of Watergate. Courtesy of Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

Courtesy of Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

The thrilling bicentennial fireworks display in New York City was a bright spot in a decade when bankruptcy threatened and the city appeared to be crumbling. Photo copyright Allan Tannenbaum.