First published 2004 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Philip Staniford 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

ISBN 13: 978-1-8452-0041-1 (hbk)

Dedicated with very great admiration to those Japanese immigrants who think they have failed because they did not achieve what they desired in the new world. They left so little in Japan to accomplish what they feel is less in Brazil. May their children prosper and build on what they did accomplish at such a high price.

PREFACE

This monograph is the result of research and fieldwork supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the United States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, whose aid and encouragement are gratefully acknowledged.

At the outset I shall make explicit my theoretical preconceptions, the nature of the research, the particular fieldwork situation and the types of data collected.

My predoctoral training has been primarily within the general framework of British social anthropology. In particular I draw heavily on the concept of network interaction as developed by Barnes (1954), Bott(i957) and Epstein(1961); exchange and power as analysed by Blau (1964); political process as described by Barth (1959) and Easton (1959).

The research consisted of two separate phases. The first was a preliminary study in Japan (from September 1963 until July 1964) with the aim of becoming proficient in spoken Japanese and acquainted with Japanese written sources on migration, consulting Japanese scholars, interviewing officials at the national and prefecture levels concerned with migrants, and making a short study of communities in Fukuoka and Kumamoto prefectures from which there has been heavy overseas migration.

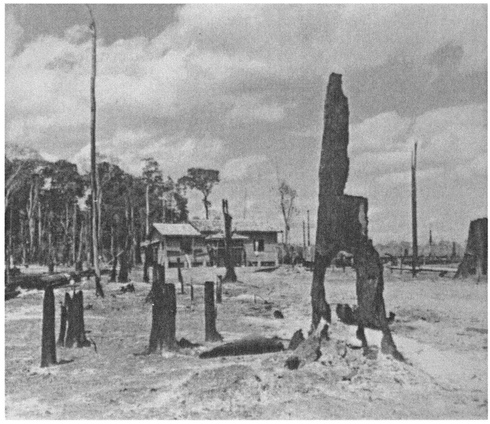

The second phase in Brazil consisted of one year's field research (from August 1964 to August 1965) in Tome A$u (pronounced tome dssu), the locale of the study, which is 125 miles up river from Belem, Pari, northern Brazil. I also interviewed Japanese and Brazilian scholars and government officials in Brazil, Tome A$u was selected for study because it is the only sizeable Japanese immigrant community in northern Brazil containing a long-established population.

Tome Au has been studied twice before. Professor Seiichi Izumi of Tokyo University had been there for one month in 1952 as a minor part of a general study of Japanese immigrants in South America financed by UNESCO's 'Social Tension Survey Project' and later by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Izumi's findings are published in Amazon; sono fdo to nihonjin (Amazon: Natural Features and the Japanese) which appeared in 1954. He collected census and ethnographic data on the general aspects of life and overt ideology of Tome A$u Japanese from schedules and closed question interviews. He gives an informative account of the immigrants just before they began to profit from their newly planted cash crop.

The second study is that of Professor Masao Gamo of Meiji University, who was in Tome Au for three months in 1955. His findings were published in 1956 in Imin (Immigrants), which deals with a number of Japanese settlements in South America. Gamo gives a general description of Tome A$u during a period of rapid transition and internal stress, when the first post-war immigrants were becoming independent.

This material, particularly Izumi's schedules, greatly assisted my own research by facilitating my initial orientation and making possible the cross-checking of informants' statements.

Both in Japan and Brazil, I was accompanied by and greatly aided by my wife, Setsuko Arai Staniford, who has a bachelor s degree in Japanese law. She helped me particularly by translating Japanese written sources, since although I obtained fluency in spoken Japanese, my ability to read and write the language is limited. In Tome A$u we carried out the field work as a team. Her presence, cross-checking and added insights greatly increased my perception of the subtleties of interpersonal communication, which can be considerable in Japanese. She caught many nuances which I alone might have overlooked. As a sympathetic and attractive Japanese woman she encouraged confidences that I would never have been able to elicit. Furthermore, she was able to collect information from women who never would have spoken freely to a male investigator. Without her vital contributions this work would never have achieved its present form.

Our united entry into Tome Au was assured by letters of introduction from Professor Izumi and Japanese immigration officials. At first we stayed in the house of a retired president of the producers' co-operative (the 'grand old man' of Tome A$u. See pp. 137-8 and 171). But although his house was politically neutral, it was some distance from those of most of the Japanese farmers, so we made arrangements to occupy a house belonging to the co-operative president (see pp. 138, 133-5) which was more centrally located. Thus initial contact came through the elite who exercised political control over the other Japanese settlers. Material was gathered at this level for the first six months.

Essential data from other segments of the society were not freely offered as long as I was considered to be in the pocket of the elite. To compensate for this I prepared a comprehensive questionnaire dealing, among other things, with critical evaluation of the leaders. The latter insisted on helping me by distributing this. Roughly 120 questionnaires (thirty per cent) were returned. I then proceeded to go personally from house to house to interview those who had failed to answer the questionnaire openly. Eventually 384 questionnaires (ninety-six per cent) were completed.