THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2023 by Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

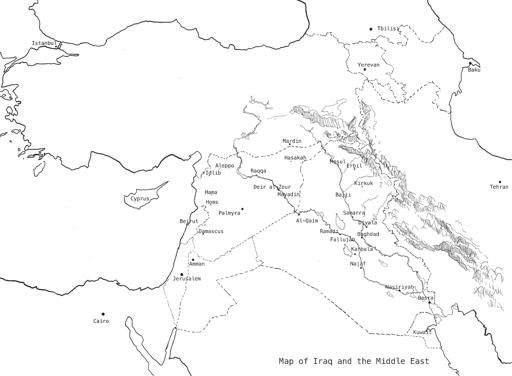

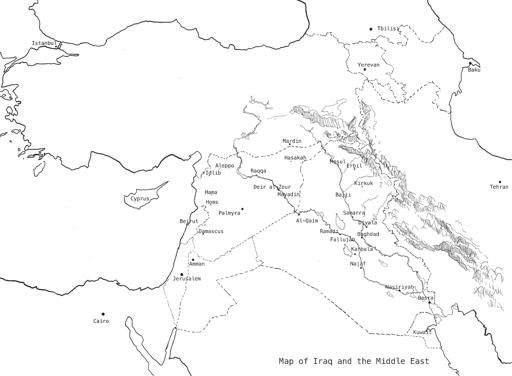

Illustrations and maps by Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Hutchinson Heinemann, an imprint of Cornerstone, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2023. This edition published by arrangement with Hutchinson Heinemann, an imprint of Cornerstone, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Abdul-Ahad, Ghaith, author.

Title: A stranger in your own city : travels in the Middle Easts long war / Ghaith Abdul-Ahad.

Description: First American edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2023.

Summary: An award-winning journalists powerful portrait of his native Baghdad, the people of Iraq, and twenty years of warProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022048464 (print) | LCCN 2022048465 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593536889 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593536896 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Abdul-Ahad, Ghaith. | Iraq War, 2003-2011Personal narratives, Iraqi. | Baghdad (Iraq)Description and travel. | Baghdad (Iraq)History. | IraqDescription and travel.

Classification: LCC DS 79.9. B 25 A 24 2023 (print) | LCC DS 79.9. B 25 (ebook) | DDC 956.7044/3dc23/eng/20221018

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022048464

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022048465

Ebook ISBN9780593536896

Cover photograph Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

ep_prh_6.0_142845113_c0_r0

Iraqis and palm trees. Who resembles whom? There are millions of Iraqis and as many, or perhaps somewhat fewer, palm trees. Some have had their fronds burned. Some have been beheaded. Some have had their backs broken by time, but are still trying to stand. Some have dried bunches of dates. Some have been uprooted, mutilated and exiled from their orchards. Some have allowed invaders to lean on their trunk. Some are combing the winds with their fronds. Some stand in silence. Some have fallen. Some stand tall and raise their heads high despite everything in this vast orchard: Iraq. When will the orchard return to its owners? Not to those who carry axes. Not even to the attendant who assassinates palm trees, no matter what the color of his knife.

Sinan Antoon, The Corpse Washer

Contents

_142845113_

Authors Note

This book is a work of nonfiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. The majority of the stories told here took place in the midst of violence and civil wars, and in many cases the people featured in these storiesboth the victims of that violence and its perpetratorsasked for their names to be changed for their protection.

A lot of literature has been published on Iraq and the rise of the Islamic State and sectarianism in the region, and the author is indebted to many writers and journalists for their brilliant books on these subjects. In particular: Charles Tripps A History of Iraq, Samuel Helfonts Compulsion in Religion, Johan Franzns Pride and Power, Fawaz Gergess ISIS: A History, and of course the mighty Hanna Batatu and his authoritative work The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq.

Prologue

Hotel room. Baghdad, 2007.

Late at night, I am awake in my hotel bed, listening to the sounds of a city at war: the distant thuds of mortars crashing in the Green Zone, the monotonous din of supply convoys, shrouded in the safety of the dark curfew hours. There are rumblings in the street below, and the howling of street dogs. Dawn will break soon; the clashes will resume. Car bombs will start blowing up in the morning rush hour. The sounds, like the war, have become repetitive, rhythmic and very predictable.

Like insomniacs counting sheep to fall asleep, I play my own game; sifting through the faces of friends from the pre-invasion days, I try to place each one on the sectarian map of a fragmented city. Tonight, I mentally run through a faded school picture, taken on a spring day in 1991, just before the second Gulf War; a group of friends in high-waisted jeans and tucked-in T-shirts, posing in front of the tall, imposing brick facade of the Jesuit-builtsubsequently nationalisedschool. Scrawny limbs, hollowed chests, childish and naughty eyes, and the first traces of moustaches lining their lips.

I try to imagine their lives in the context of the civil war raging outside my hotel room. Who was a Shia, and who was a Sunni? How many were kidnapped and how many killed? How many members of militias and how many in exile?

Those with easy-to-classify family names emerge first. Ahmad must be a Shia. Raid is a Sunnihe used to be proud of a distant tribal relation to the Great Leader, an association that must haunt him in these days of Shia death squads. Basil was Christian and had long since left Iraq. The game is hard, old memories cant always be translated into the latest sectarian terminology, and I fail to place most of my friends on the new sectarian map of Baghdad.

The poet who I presumed to be a Shia, just because he lived close to the Shia shrine in Khadimiya, turned out to be a Sunni from Mosul. He dallied with radical Islam, grew a long beard, and flirted with Sunni insurgents, before fleeing from Shia death squads into Syria. He could have been a useful contact in these days, but when a few years later I met him in Dubai, he drank his whisky neat and was back to writing poetry. The young boys from the high school picture are now scattered between Dubai, Amman, Liverpool and Toronto. A neurosurgeon, a paediatrician, an architect, a civil engineer and a couple of university professors, a businessman who twice made a multimillion-dollar fortune and twice lost it on the stock market. Alas, none is a vicious militia commander; there are no sectarian politicians and no killers among them. They are useless friends in a Baghdad torn by civil war, where one needs contacts among the different fighting groups to help negotiate the multiple front lines. I have become a stranger in my own city.

The hotel bed is narrow with a pale wooden frame, sagging in the middle where two planks are missing. The room is heavy with the dust of two decades of War, Sanctions and Occupation. Two car bombs have left long, thin cracks on the walls; plastic sheeting covers a broken window, and pipes are dripping in the bathroom, where layers of grimy green mould carpet the corners. The hotel was once a fashionable enterprise with the sharp, concrete corners of brutalist architecture, chic seventies furniture and an excellent bakery. The swimming pool, with its deep blue tiles, was elegant and exceptionally clean. The cold, over-chlorinated water frothed in little waves over the edge, and floating eucalyptus leaves would cast twirling shadows on its blue tiles before being scooped up by a diligent staff member. A long-life ago, I swam here every summer. A benevolent, wealthy, formerly Communist grand-aunt paid my entry fees; she also introduced me to Russian literature and ailurophilia. I used to sit at one of the white plastic tables by the poolside playing Uno with other boys and girls. We ate melon, ice cream and sometimes, if we could afford it, croissant sandwiches. When most of the guests left, we stayed behind, racing each other in the pool, or swimming endless laps until it was dark and too cold.