For Kate, Leo and Max

Contents

| ADC | Aide-de-Camp |

| AFC | Australian Flying Corps |

| AG | Adjutant-General |

| APO | Assistant Political Officer |

| APOC | Anglo-Persian Oil Company |

| AQMG | Assistant Quartermaster-General |

| BO | British Officer |

| C-in-C | Commander in Chief [also GOC-in-C] |

| CC | Civil Commissioner |

| CGS | Chief of the General Staff |

| CIGS | Chief of the Imperial General Staff |

| CRA | Commander Royal Artillery |

| DAAG | Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General |

| DAQMG | Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General |

| DMI | Director of Military Intelligence |

| DMO | Director of Military Operations |

| DMS | Director of Medical Services |

| GHQ | General Headquarters |

| GOC | General Officer Commanding |

| [GOC-in-C | General Officer Commanding-in-Chief] |

| GSO | General Staff Officer |

| IEF | Indian Expeditionary Force |

| IMS | Indian Medical Service |

| IO | Indian Officer |

| HLI | Highland Light Infantry |

| HMG | His Majestys Government |

| LI | Light Infantry |

| LofC | Line of Communications |

| MAC | Mesopotamia Administration Committee |

| MED | Middle East Department |

| MEF | Mesopotamia Expeditionary Force |

| MO | Medical Officer |

| OC | Officer Commanding |

| OP | Observation Post |

| PO | Political Officer |

| QMG | Quartermaster-General |

| RAF | Royal Air Force |

| RE | Royal Engineers |

| RFA | Royal Field |

| RFC | Royal Flying Corps |

| RNAS | Royal Naval Air Service |

| SNO | Senior Naval Officer |

| WO | War Office |

When I set out to write this book, I was conscious of the pioneering work done by A. J. Barker in his book The NeglectedWar, published by Faber in 1967. That book was strong on military detail, but less so on the political dimensions of the Mesopotamia campaign. I hoped to adjust this balance. In the course of writing, my respect for Colonel Barkers achievement increased, and I hope my debt to his work is clear even where it is not explicitly acknowledged. I am most grateful to a number of very helpful keepers of archives, especially at the Imperial War Museum, the National Army Museum, and the Middle East Centre at St Antonys College, Oxford. The National Archives, despite abandoning their hallowed and globally recognised title of Public Record Office, now provide a wonderfully improved service, fast and accessible, a world away from that in which I started research forty years ago.

My editors at Faber, Neil Belton and Kate Murray-Browne, both ploughed through drafts of the book with admirable tenacity, and produced careful and helpful critiques, as also did Roy Foster. Richard Holmes gave me the benefit of his unparalleled expertise on many occasions. Neil first put the idea of the book to me, and came up with the title. The book itself may, I fear, perhaps not quite match his original vision, but I hope it goes some way towards it.

It has been an odd experience to write a book with a key character bearing the same name as me. I first read Charles Townshends book many years ago, and once pulled up his personal file from the War Office records a bulging folio of hard-done-by grumbles. I am not related to him, as far as I know, and I felt no need to defend his reputation, but in working on this book I came to the conclusion that he was in some ways hard done by. I hope that in assessing the many criticisms of him I have not strayed too far from the path of critical detachment.

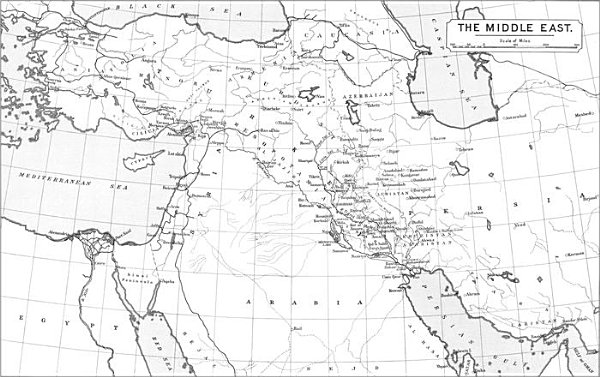

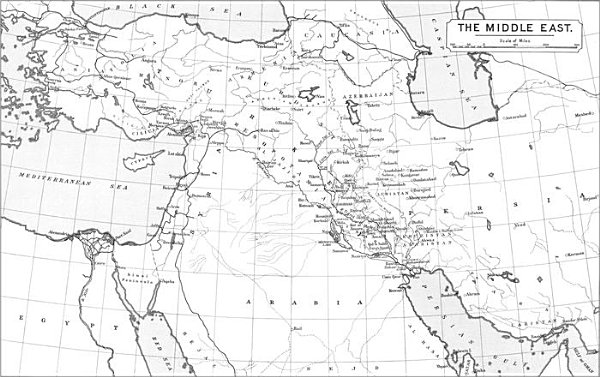

The Middle East in 1914

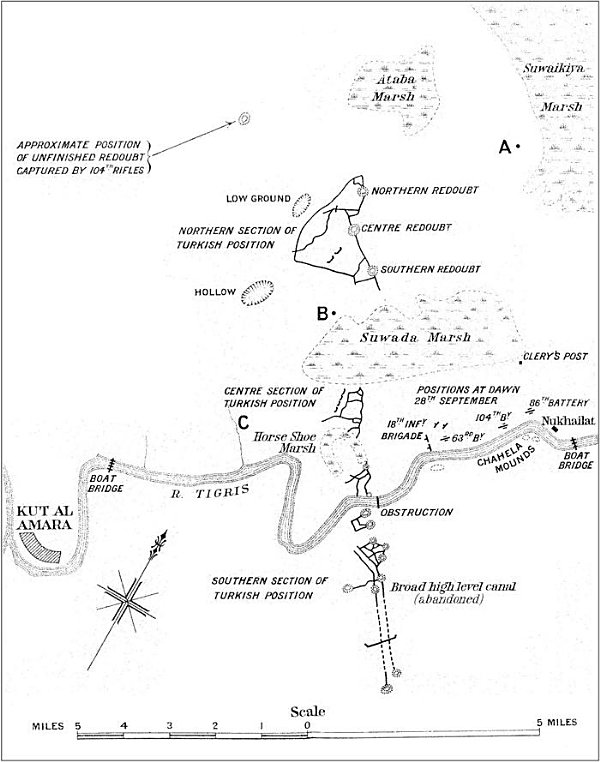

The Battle of Kut, September 1915

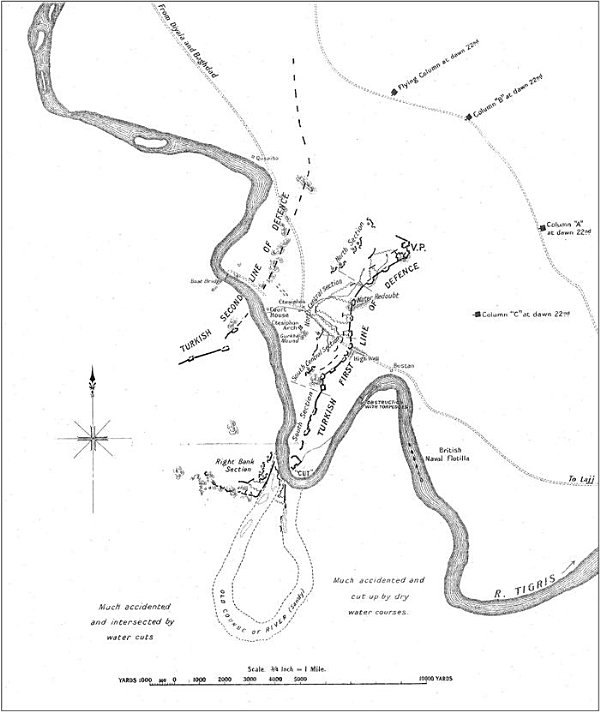

The Battle of Ctesiphon, November 1915

The Battle of Kut (Sheikh Saad), September 1915

The Battle of Ctesiphon, November 1915

Since the Coalition conquest of Iraq in 2003, British people have come to know more about that country than at any time since Iraq became a state after the First World War. How well they understand Britains role in creating that state is harder to say. But it is no exaggeration to say that modern Iraq was created, deliberately and unilaterally, by the British over the seven years following their first invasion in 1914. Recent history contains few examples of such dramatic and fateful intervention.

Creating a new state was certainly not one of the objectives of the British military expedition which entered the country known in the West as Mesopotamia in 1914. That move began a sequence of unintended consequences. This will not surprise students of history, though it should probably be emphasised for the makers of national policy. Iraq was a geographic expression rather than a political entity the provinces of Basra and Baghdad. It was a remote and rebellious corner of the Ottoman Empire. The rebelliousness of its Arab people stemmed not from nationalist objection to Turkish rule, but from the resistance of traditional tribal groups to Ottoman government; in part this was Shia resistance to Sunni control. There were few Arab nationalists, and fewer Iraqi nationalists, to point the way to the political future.

The expeditions aims were primarily strategic. The Ottoman Empire was the worlds only remaining Muslim state, and if Britain went to war with it as seemed almost inevitable in September 1914 a wider Islamic movement, perhaps even a religious war, could spread through Persia and threaten the security of the British Raj in India. The display of British military power was aimed at impressing the Arabs, and supporting Britains key allies in the Persian Gulf region, the Sheikhs of Kuwait and Mohammerah (now Khorramshahr). Oil was also an issue, but a secondary one in 1914. Britain had part ownership of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which had begun to pump oil in 1912. The companys oilfields in southern Persia, and the pipeline to its refinery at Abadan on the Shatt-al-Arab, the border between Persia and the Ottoman empire, were strategically important. But Britain did not use its own military forces to guarantee their security: this was done economically by arrangement with a local potentate, the Sheikh of Mohammerah. The oil in Mesopotamia itself did not loom large in British strategic calculations when the war broke out. But by the time it ended, this was changing. The potential oil resources of Mosul province were beginning to exert an influence on the developing idea of establishing an Arab state in the conquered territory.

An Arab state was a remote prospect in 1914. The Mesopotamia expedition was sent by the British Government of India; and the rulers of India had a low opinion of Arab political capacity. More importantly, they had no wish to see an Arab state emerge in an area of British paramountcy. Some actually foresaw the transformation of Mesopotamia into an Indian colony, where the colonists might outnumber the natives ten to one. The people responsible for administering the territory occupied by the expeditionary force pursued a policy that diverged from the British governments policy. During the war, a new world order emerged based on the principle of national self-determination. By 1918 Britain was committed to this principle, but the men who governed Iraq in its name believed that self-determination was a sham.