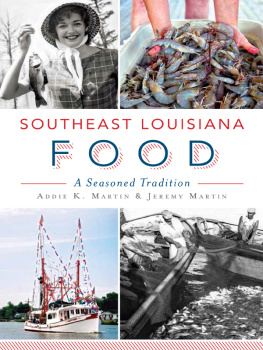

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by Addie K. Martin, Jeremy Martin and Culture Curious, LLC

All rights reserved

Cover images: Courtesy of Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Mary Chailland and the authors.

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62585.079.9

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.549.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to the many generations of fishermen and cooks in Southeast Louisiana, past, present and future.

If the Midwest is the nations breadbasket, South Louisiana is its seafood platter.

Windell Curole in the film No One Ever Went Hungry by filmmaker Kevin McCaffrey

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Were ever so grateful to all of the people who helped to make this book possible. It truly takes a village of like-minded people devoted to a common cause to make something happen.

For the professional resources, interview time, keen insights and a seemingly tireless commitment to Southeast Louisianas fisheries, food and culture, we thank Marcelle Bienvenu, Nick Collins, Dr. Don Davis, Madeline Maddie Futrell, Jim Gossen, Tom Hymel, Brian Landry, Kevin McCaffrey, Mark Schexnayder, Carol and George Terrebonne and Liz Williams.

We also thank family and friends whove contributed significantly along the way. Theyve helped us greatly in a variety of ways, mainly via formal and informal discussions, recipe contributions, loaned photos and drawings, resources, connections and, above all, moral support and encouragement: Dr. Patricia King Bollinger, Mary Constransitch Chailland, Brent Constransitch, Chester Constransitch, Tynette Constransitch, Dionne Grayson, Jennifer Lloyd, Rahlyn Gossen, Adam Guidry, Joy King Guidry, Jesse King, Rudy King, Jason Saul and Frederick Stivers.

Finally, thanks to the important people in our lives who listened when we needed a sounding board for ideas or when we simply needed a supportive ear. Thank you to those people who knew just the right thing to say when we needed to hear it. Many thanks to those whose enthusiasm for our work seems endless. Finally, perhaps most significantly, our sincere appreciation goes to you, the reader, who cracked open a copy of this book today.

Our gratitude to you all is endless.

INTRODUCTION

A BOOK IS BORN

The two of us are out at the camp, sitting, legs dangling over the side of the little dock, watching the setting sun turn the dull summer green of the marsh grass into something more like gold. From the camp shack behind us, a light crackling sound sure enough delivers the smell of frying fishthe days catch cleaned and rough hewn with a fillet knife into manageable chunks and fried in a shallow cast-iron pan. Dinner will be soon, but for now, we are just sitting, watching the lazy waves of marsh grass dance and thinking, I am from here, thinking about what it means to be from somewherewhat it means to be from Southeast Louisiana. The implications of this idea press down on us as thick as the humid air. The earth is home to a staggering diversity of life. You can sit here on this pier and watch life swim, walk and fly right past you. As life develops, though, so does culture. It evolves differently depending on varying environmental factors such that each culture inhabits its homeland uniquely. Intrigued by this, we discuss over the simple, gas-lit plank table the nature of being from Southeast Louisiana and what it means to be a part of this culture or of any culture at all.

We walk into the close, still air of the camp shed and sit around the table, where we talk with full mouths about how cultural exchanges have always occurred between wildly diverse cultures. We talk about the way it must have been centuries ago, when the peril of travel often limited cultural communication to isolated exchanges such as the trade of valuables and, of course, wars over resources. However, its obvious that in the past three centuries, long-distance travel has become ever more accessible, and this easing of geographic boundaries has led to the creation of diverse melting-pot nations such as the United States. The United States is home to representatives of almost every cultural group in existence. Some of these groups can be found in urban enclaves, others in rural settings that are similar to their homelands and many are scattered across the nation, contributing their own unique traditions to the rich fabric of American culture. Today, the well-known immigrant centers of the urban Northeast, West Coast and, increasingly, the southern border have been shaped not only by their environments but also by the people who have decided to call them home. However, centers of immigration change with trade patterns and shifts in population and political priorities. At various times in its history, Southeast Louisiana, too, has seen its share of immigration. Prior to the Civil War, New Orleans was the second-largest immigration port in America behind New York City. From the well-known influx of French Acadians to other Europeans to Southeast Asians and now Central Americans, the ports of Southeast Louisiana have been as heavily shaped by immigration as any other part of the country.

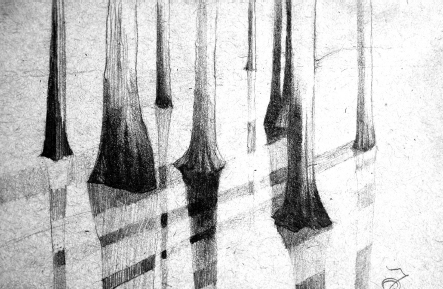

Drawing by Frederick Stivers, 2014.

All we have to do is look at the map of the region, hanging water-stained by hurricanes on the wall, to realize that Southeast Louisiana is nothing more than a giant port, directly connected by water to a basin, which drains 1.25 million square miles of North America. The interior of North America was created by sediment carried by the Mississippi River and cannot be accessed by water without passing through Southeast Louisiana. The region has been shaped by the river, the wetlands the river creates and the cultures of the immigrants who have come to make a living. These cultures were attracted by the bounty of southeastern Louisianas vast wetland delta, which provides home for all manner of aquatic (and aerial and terrestrial) wildlife. It is the same reason that many people, including us, live here today. It is why were out here in the dying summer light amidst the snow-like quiet of the marsh. The bounty of this place is what feeds us around this table tonight, the same way it has fed nine generations or more of Louisianians just like us.

We are quite familiar with the fact that one of the biggest facets of any cultureespecially oursis its food: what people eat, how they cook, how they grow or raise it, what they do when they eat. In Southeast Louisiana, a number of regional foods contribute to the vibrant and distinct culture. These food cultures, or foodways, are centered on the thin strips of high ground that texture the Mississippi River Delta. Modern Cajun fare is an invention and byproduct of the twentieth century. Two centuries of culinary evolution created this cuisine via the melding and influence of many cultures and cuisine types. These foods are predominantly harvested wild from the shallow marsh waters and offshore in the Gulf of Mexico. Encompassing oysters, crabs, crawfish, shrimp and finfish, each of these foods is reflected not only in the regions dishes but also in the social fabric of cultures as varied as French, German, Spanish and American Indian. These food commodities become cultural artifacts themselves and provide a lens we can peer through to understand the development of various groups of peoples whose comparative isolation in the delta has allowed the parallel development of cultures from each other and the United States as a whole.

Next page