Introduction

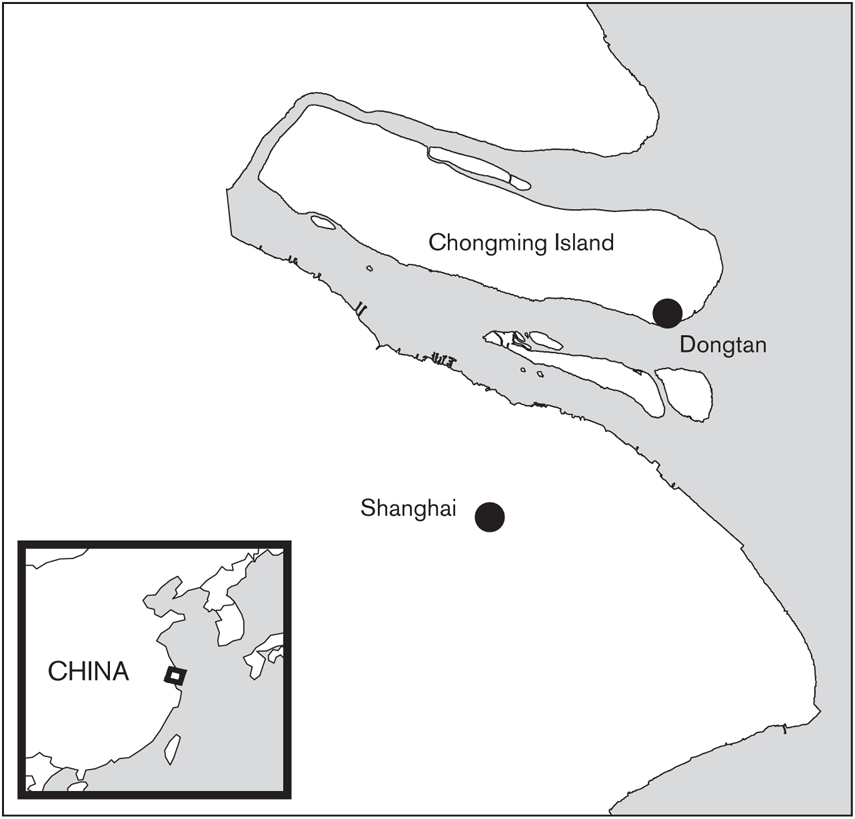

I stood on a wooden deck overlooking the Dongtan wetlands in the blistering August heat and humidity. The wetlands are a stopover on the East AsiaAustralia migratory shorebird flyway and located on the eastern edge of Chongming Island. The island is located twenty miles east of Shanghais glitzy downtown, seven miles across the Yangtze River. It is the worlds largest alluvial island, formed by deposits from the river. The island has doubled in size since the 1940s, and it is either the second or third largest island in China. Chongming is on the proverbial rise, fast-tracked for ecological and economic development of all kinds (Chongming was rumored to be the site for the first mainland Chinese Disneyland, a prize lost in 2009 to the Pudong district). According to the county website, Chongming Island is a tourist attraction for urban people to find a return to nature where they can experience a spiritual integration of humans and nature.

I wasnt here to look for a return to nature or to birdwatch. Rather, I was here to see something that was supposed to be here but was never built: the worlds first great eco-city. In its glaring absence, I saw something else: what eco-dreams and fantasies are made of, in an age of emergent global climate crisis.

Map 1. Map of China, Shanghai, and Chongming. Cartography: Michele Tobias

DONGTAN: THE QUEST TO CREATE A NEW WORLD

Dongtan and Chongming were all over the international news in 2006 with the announcement of the worlds first major eco-city. Dongtan eco-city was slated to accommodate a population of five hundred thousand people by 2050, and to be a carbon-neutral and zero-waste city where all inputs for energy come from collected waste, using renewable sources and technologies. Dongtan was to be built by Arup, the UK-based global planning, engineering, and design firm, for the Shanghai Industrial Investment Corporation (SIIC), the investment arm of the Shanghai municipality. Dongtan was supposed to exemplify a green approach to urban design, architecture, infrastructure (including sustainable energy and waste management), and economic and business planning.

Arup described Dongtan as the quest to create a new world. This quest included a different model for Chinese urbanism, one that explicitly rejected the idea that one must have economic development first and environmental protection second. Rather, this model asserted that economic growth and environmental protection go hand in hand. Arups original master plan for Dongtan had a planning trajectory of forty-five years and was intended for completion in 2050. As imagined, Dongtan was to be three quarters the size of Manhattan. The plan provided twenty-nine square meters of green space per person, more than four times the amount in Los Angeles, and which also ensured that no place in the city was farther than 540 meters from a bus stop (a density of 160 people per hectare was planned to make public transportation feasible). The Dongtan plan was divided into two sections: an eighty-six-square-kilometer conservation area of farmland and aquaculture; and exterior wetlands on the sea side of the 1998 dyke. Dongtans ecological footprint was modeled as less than half that of a typical Chinese city. Ninety percent of all waste was to be recycled; and 95 percent of all energy was to come from renewable sources. Biogasification of rice husks was to supplement wind and solar power. Only cars with zero tailpipe emissions were to be allowed inside the city; all others were supposed to be left in a parking lot on the edge of the development. Dongtan city was to be formed through the integration of three towns (Marina Village, Lake Village, and Pond Village). In addition to the town and city plan, the comprehensive master plan included three leisure parks, each focused on a different theme: equine and water sports, science education, and vacation villas.

Dongtans vision was big business and politics, involving leaders of nations and heads of international architectural, engineering, and design firms. When I first heard about Dongtan, I almost fell off my chair. I was pleasantly surprisedand thoroughly confused. My father was born and raised on Chongming and we still have extended family there. Growing up, I associated Chongming with being rural. Now it was supposed to be the site of the worlds most cutting-edge eco-city, around which China and the United Kingdom were modeling the future of Chinese cities. For me, Chongming was the repository of complex ideas and emotions, a place my family, old relatives, and family friends were from. When I was growing up, my mother would routinely make fun of my fathers occasional slipping into the Chongming dialect (distinct from the Shanghai dialect that they shared). Their teasing was an en famille reprise of the divide between city sophisticate and country bumpkin. How did Chongming become the staging ground for the bold new eco-future for Shanghai? What did it all mean?