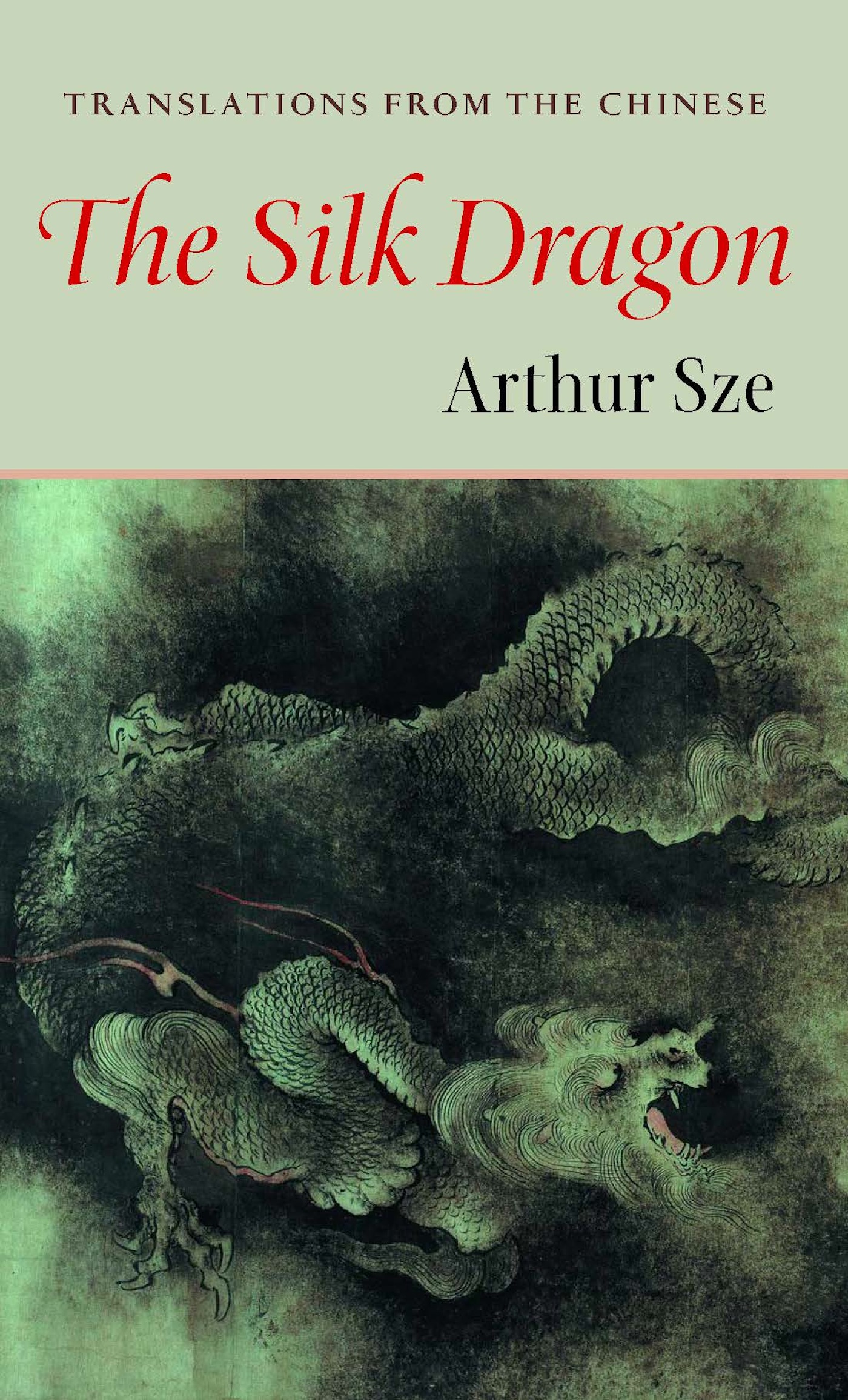

Sze - The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry

Here you can read online Sze - The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Port Townsend;WA, year: 2000;2001, publisher: Copper Canyon Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sze: author's other books

Who wrote The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

We hope you enjoy these poems. This e-book edition was created through a special grant provided by the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. Copper Canyon Press would like to thank Constellation Digital Services for their partnership in making this e-book possible.

Morgan C.Y. Sze & Agnes C. Lin Sze

In 1971, as a student at the University of California at Berkeley, I majored in poetry. Also studying Chinese language and literature, I became interested in translating the great Tang-dynasty poetsLi Po, Tu Fu, Wang Wei, among othersbecause I felt I could learn from them. I felt that by struggling with many of the great poems in the Chinese literary tradition, I could best develop my voice as a poet. Years later, in 1983, after publishing Dazzled, my third book of poetry, I translated a new group of Chinese poems, again feeling that it would help me discern greater possibilities for my own writing. I was drawn to the clarity of Tao Chiens lines, to the subtlety of Ma Chihyans lyrics, and to Wen I-tos sustained, emotional power. In 1996, after completing my book Archipelago, I felt the need to translate yet another group of Chinese poems: I was particularly drawn to the Chan-influenced work of Pa-ta-shan-jen and to the extremely condensed and challenging, transformational poems of Li Ho and Li Shang-yin.

I know translation is an impossible task, and I have never forgotten the Italian phrase traduttori/traditori: translators/traitors. Which translation does not in some way betray its original? In considering the process of my own translations, I am aware of loss and transformation, of destruction and renewal. Since I first started to write poetry, I have only translated poems that have deeply engaged me; and it has sometimes taken me many years to feel ready to work on one. I remember that in 1972 I read Li Shang-yins untitled poems and felt baffled by them; now, more than twenty-five years later, his versesveiled, mysterious, and full of longingstrike me as some of the great love poems in classical Chinese. To show how I create a translation in English, I am going to share stages and drafts of a translation from one of Li Shangyins untitled poems. I like to begin by writing the Chinese characters out on paper.

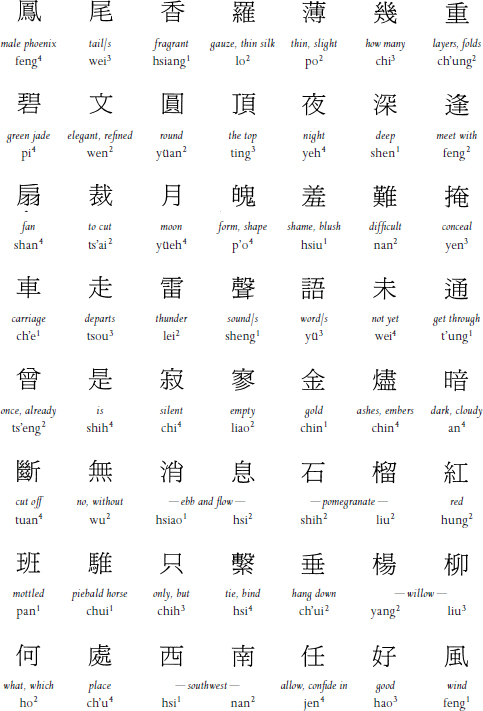

I know that my own writing of Chinese is awkward and rudimentary, but, by writing out the characters in their particular stroke order, I can begin to sense the inner motion of the poem in a way that I cannot by just reading the characters on the page. Once Ive written out the characters, I look up each in Robert H. Mathewss Chinese-English Dictionary and write down the sound and tone along with a word, phrase, or cluster of words that helps mark its field of energy and meaning. I go through the entire poem doing this groundwork. After I have created this initial cluster of words, I go back through and, because a Chinese character can mean so many different things depending on its context, I remove words or phrases that appear to be inappropriate and keep those that appear to be relevant. In the case of Li Shang-yins untitled poem, I now have a draft that looks like the figure on the facing page.

In looking at this regulated eight-line poem, I know that each of its seven-character lines has two predetermined caesuras, so that the motion in Chinese is 12/34/567. I try to catch the tonal flow and sense the silences. I know that the tones from Mathewss dictionary only give me the barest approximation. Tang-dynasty poems are most alive when they are chanted. The sounds are very different from the Mandarin dialect that I speak. Yet I can, for instance, guess that the sound of tuan4, the first character in line six, is sharp and emphatic.

I also sense that characters three and four in line sixhsiao1 and hsi2have an onomatopoeic quality to suggest ebb and flow. In double-checking this phrase in the dictionary, I realize it has the primary meaning of news and information; there is no news, and the speaker is in a state of heightened isolation. In looking at the visual configuration of the characters, I am again struck by the first character in line six, tuan4. Here the character contains the image of scissors cutting silk, and I wonder if this can be extended to develop an insight into the poem.  I proceed by writing a rough draft in English: trying to write eight lines in English that are equivalent to the eight lines in Chinese. I realize immediately that the translation is too cramped.

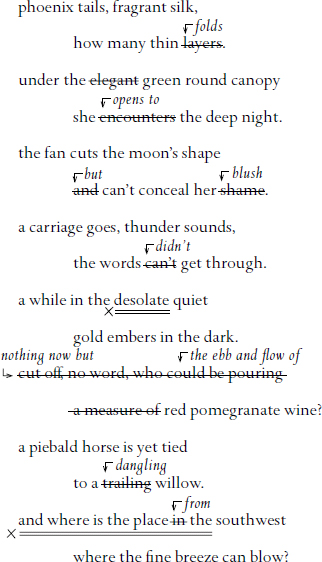

I proceed by writing a rough draft in English: trying to write eight lines in English that are equivalent to the eight lines in Chinese. I realize immediately that the translation is too cramped.

I look back at the Chinese and decide to use two lines in English for each line of Chinese. I also decide to emphasize the second caesura of each line in Chinese so that in English theres a line break after the meaning of the fourth character in each line of the Chinese original. I write out another draft in which sixteen lines in English now stand for the eight lines in Chinese. All of the lines in English are flush left, but the blocklike form does not do justice to the obliquely cutting motion of the poem. To open it up and clarify the architecture, I decide to indent all of the even-numbered lines. I go through another series of drafts, which oftentimes incorporate English words that Ive listed on the page with Chinese characters, though I dont feel compelled to use all of them.

At this transitional stage, I have something that looks like the following version (without any of the crossed-out or underlined words):  At this point, if there are books of Chinese translations that I think might be helpful, I look at them to see if they have any commentaries that are relevant. In Franois Chengs Chinese Poetic Writing I find that lines one and two describe the bed-curtain of a bridal chamber, that to pluck a willow branch means to visit a courtesan, that red pomegranate wine might be served at a wedding feast and connotes explosive desire, and that the southwest breeze alludes to a phrase by Tsao Chih (192232), I would become that southwest wind / waft all the way to your bosom. I find these comments insightful but do not want to incorporate them overtly into my translation. Because Li Shang-yins great strength is his oblique exactitude, I want my translation to hint at these elements. I now look at my very rough translation and go back to the original Chinese. My experience of the poem is that a solitary woman is lamenting the absence of her lover and longs for him even as she worries that he is unfaithful.

At this point, if there are books of Chinese translations that I think might be helpful, I look at them to see if they have any commentaries that are relevant. In Franois Chengs Chinese Poetic Writing I find that lines one and two describe the bed-curtain of a bridal chamber, that to pluck a willow branch means to visit a courtesan, that red pomegranate wine might be served at a wedding feast and connotes explosive desire, and that the southwest breeze alludes to a phrase by Tsao Chih (192232), I would become that southwest wind / waft all the way to your bosom. I find these comments insightful but do not want to incorporate them overtly into my translation. Because Li Shang-yins great strength is his oblique exactitude, I want my translation to hint at these elements. I now look at my very rough translation and go back to the original Chinese. My experience of the poem is that a solitary woman is lamenting the absence of her lover and longs for him even as she worries that he is unfaithful.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry»

Look at similar books to The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The silk dragon: translations of chinese poetry and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.