To

Frances Ann-Marie Miles

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Archaeology

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

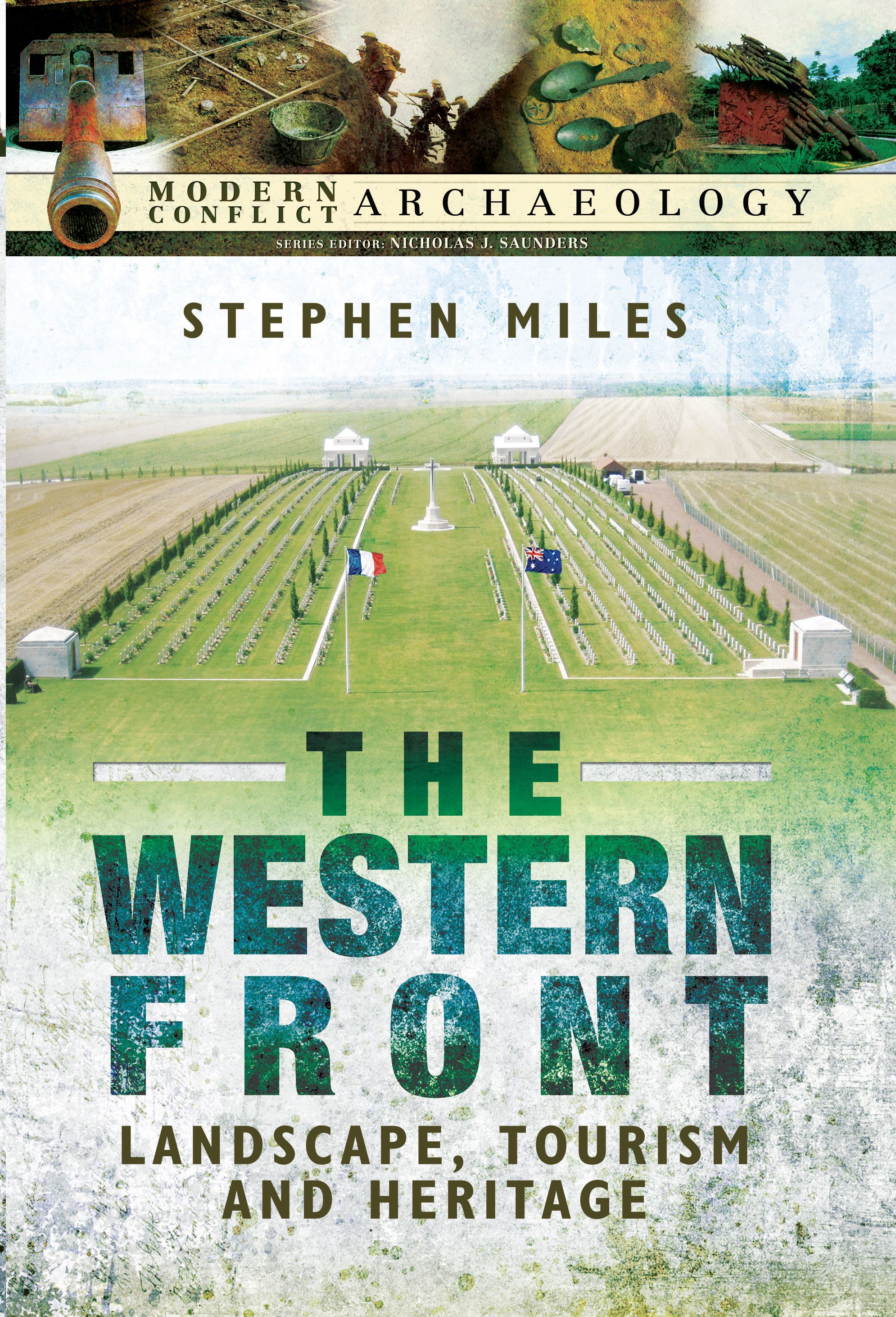

Copyright Stephen Miles 2016

ISBN 978 1 47383 376 0

The right of Stephen Miles to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

F irstly I would like to thank my editor Professor Nick Saunders at the University of Bristol for his continuing commitment and patience in steering this project to its conclusion. His advice was absolutely indispensable and is greatly appreciated. It was most reassuring to have such an experienced writer and academic as editor for this my first book. At Pen and Sword Books I would like to thank Eloise Hansen and Heather Williams, very able Commissioning Editors, who were consistently helpful and attentive.

Many people have helped me with the research for this book but in particular I would like to thank the following: in Belgium and France Dominiek Dendooven and Piet Chielens, In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres; Michel Rouger and Lyse Hautecoeur, Muse de la Grande Guerre du Pays de Meaux; Steven Vandenbussche, Timby Vansuyt and Lee Ingelbrecht at the Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, Zonnebeke; Alexandre Lefevre, Somme Tourism, Amiens; Avril Williams, owner of the Ocean Villas Bed and Breakfast at Auchonvillers; and David and Julie Thomson, owners of the Number 56 Bed and Breakfast in La Boisselle, who were often my hosts. For the use of images in Belgium I would like to thank Franois Maekelberg, President of the 1914 St Yves Christmas Truce Committee, and Klaus Verscheure of the Danse La Pluie production company, Sint-Denijs. In the UK I was assisted by Anna Jarvis at the Heritage Lottery Fund and Peter Francis, Media and Marketing Manager, and Ian Small at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. I would also like to thank Dr Wanda George, Mount Saint Vincent University, Canada and Emeritus Professor Myriam Jansen-Verbeke, Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium for allowing me to use the results of the WHTRN survey.

Abbreviations

APWGBHG All-Party Parliamentary War Heritage Group (UK) CWGC Commonwealth War Graves Commission

HGG Historial de la Grande Guerre, Pronne

IFFM In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Belgium

IWGC Imperial War Graves Commission

MGGM Muse de la Grande Guerre du Pays de Meaux

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation WHS World Heritage Site

WHTRN World Heritage Tourism Research Network

WW1 World War One

A note on terminology

In this book the Somme refers to the area where the British army fought in France from August 1915; the Battle of the Somme (July November 1916) was fought along a front roughly 18 miles (29 kilometres) long stretching from Gommecourt in the north to Curlu in the south. The terms along the Somme and on the Somme refer to this geographical parcel of land and not the modern French dpartement or the river of that name.

Modern Conflict Archaeology

The Series

Modern Conflict Archaeology is a new and interdisciplinary approach to the study of twentieth and twenty-first century conflicts. It focuses on the innumerable ways in which humans interact with, and are changed by the intense material realities of war. These can be traditional wars between nation states, civil wars, religious and ethnic conflicts, terrorism, and even proxy wars where hostilities have not been declared yet nevertheless exist. The material realities can be as small as a machine-gun, as intermediate as a war memorial or an aeroplane, or as large as a whole battle-zone landscape. As well as technologies, they can be more intimately personal conflict-related photographs and diaries, films, uniforms, the war-maimed and the missing. All are the consequences of conflict, as none would exist without it.

Modern Conflict Archaeology (MCA) is a handy title, but is really shorthand for a more powerful and hybrid agenda. It draws not only on modern scientific archaeology, but on the anthropology of material culture, landscape, and identity, as well as aspects of military and cultural history, geography, and museum, heritage, and tourism studies. All or some of these can inform different aspects of research, but none are overly privileged. The challenge posed by modern conflict demands a coherent, integrated, sensitized yet muscular response in order to capture as many different kinds of information and insight as possible by exploring the social lives of war objects through the changing values and attitudes attached to them over time.

This series originates in this new engagement with modern conflict, and seeks to bring the extraordinary range of latest research to a passionate and informed general readership. The aim is to investigate and understand arguably the most powerful force to have shaped our world during the last century modern industrialized conflict in its myriad shapes and guises, and in its enduring and volatile legacies.

This Book

What to do with the war dead? How best to honour and remember them? And, how should we deal with the tensions between forgetting and remembering? One answer, as Stephen Miles shows in this path-breaking book on the First World Wars Western Front, is to visit them, or at least to journey to the places where monuments and memorials have been erected to their memory, even when they are not present by virtue of still being missing on the battlefields.

In the wake of the Armistice on 11 November 1918, battlefield pilgrimages and tours tapped into the need of the bereaved to visit the graves of, and the places associated with, their loved ones. Beginning in the 1920s, and down to the eve of the Second World War, legions of the desolate tramped across the old Western Front, chafed by grief, battlefield guides in hand, seeking a rendezvous of the spirit with the sons, fathers, brothers, husbands and lovers who had not returned. Never before or since have the dead been visited by so many of the living. But why do visitors still come a century on? What do they see today and where do they see it? How have places and attitudes changed under the pressures of Remembrance, commercialization, and the wars in-between?

Next page