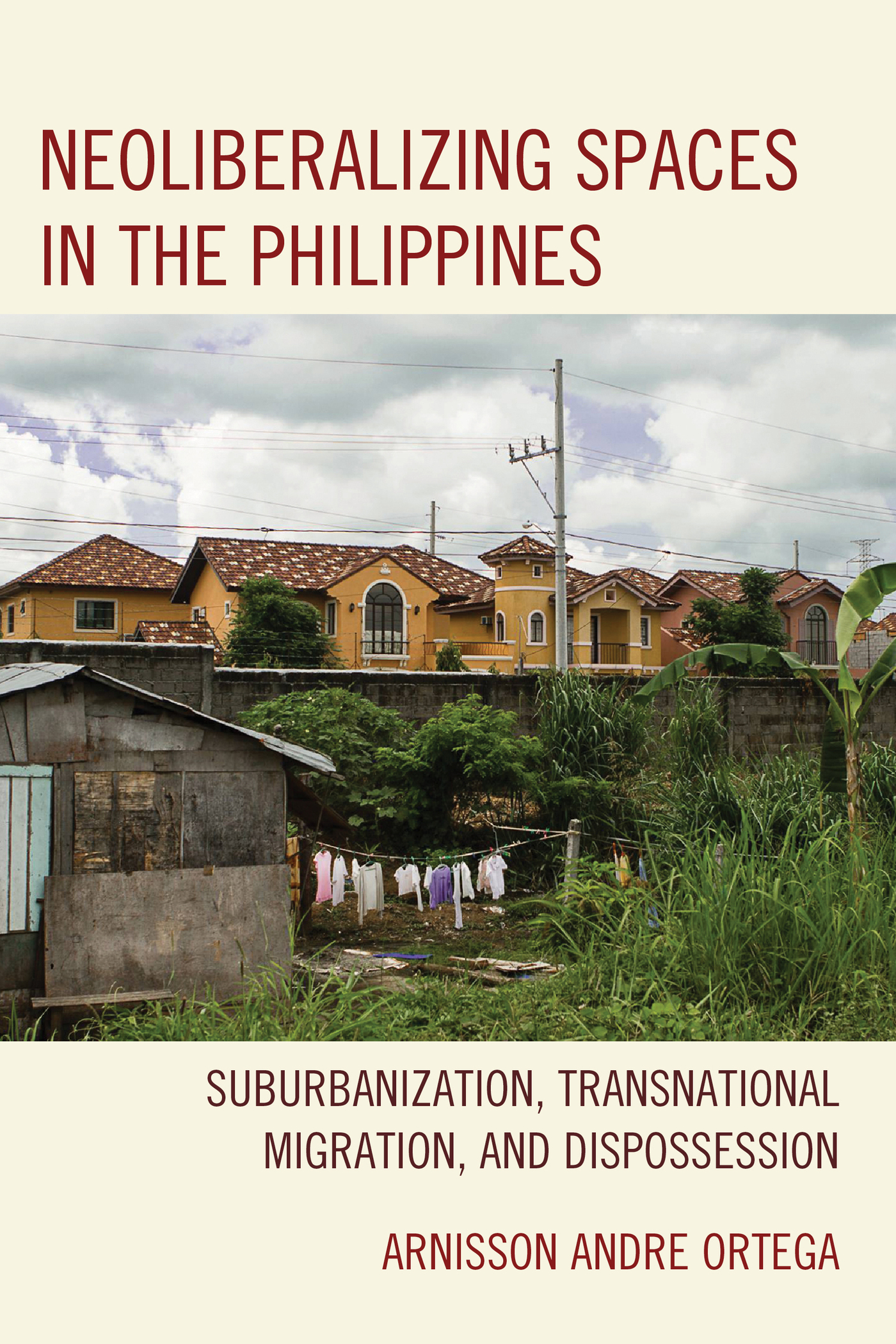

Neoliberalizing Spaces in the

Philippines

Neoliberalizing Spaces in the

Philippines

Suburbanization, Transnational

Migration, and Dispossession

Arnisson Andre Ortega

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ortega, Arnisson Andre, 1980- author.

Title: Neoliberalizing spaces in the Philippines : suburbanization, transnational migration, and dispossession / by Arnisson Andre Ortega.

Description: Lanham : Lexington Books, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016027461 (print) | LCCN 2016029213 (ebook) | ISBN 9781498530514 (cloth : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781498530521 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Real estate businessPhilippines. | Public spacesPhilippines. | SuburbsPhilippines. | Gated communitiesPhilippines. | Return migrationPhilippines.

Classification: LCC HD906.5 .O78 2016 (print) | LCC HD906.5 (ebook) | DDC 307.7409599dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016027461

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

This book is a product of years of field work and writing and would not have been possible without the help of numerous individuals and communities. I extend my sincerest gratitude to all the communities that welcomed me during my field work, in particular to the farmers and urban poor residents of Buntog and San Roque. Thanks to the activists and organizers in these communities who extended their ties of solidarity. Your unwavering dedication, courage and bravery are a constant inspiration.

I am very fortunate to have an intellectual community that has supported me over the years. In particular, I thank Katharyne Mitchell,

Vicente Rafael and Sarah Elwood for all their advice, suggestions and guidance. I am very grateful to Suzanne Davies Withers who served as my adviser at the University of Washington. At Lexington Press and

Rowman & Littlefield, I thank Brian Hill and Eric Kuntzman for their patience and belief in this project. I also thank Ashleigh Cooke for

overseeing the production and copyediting of the book.

This book is based on studies financed by several organizations. A Fulbright scholarship and Intel Consumerism Grant facilitated my early work at the University of Washington. At the University of the Philippines, the Office of the Vice President for Academic Affairs funded my project on mapping Manilas peri-urban fringe.

In the University of the Philippines, I am very fortunate to find a home at the UP Population Institute. I thank my colleagues for their patience and understanding: Midea Kabalaman, Maria Paz Marquez, Grace Cruz, Elma Laguna, Nimfa Ogena and Josefina Natividad. I also thank Joy Cruz, Armand Kamhol and the rest of the staff of the institute. My research assistants, Celes Hermida and Astrid Acielo warrant special mention.

I thank my family, relatives and friends for all their support. Salamat to my Nanay Nida, Tatay Arturo, Allan, and Lisa. I thank my Lolo Joe, Lola Angeling, all my tita and tito, and cousins. I thank my friends for their encouragement and affection: Vanessa Banta, Anna Malindog, John Uy, Vivo Regalado, Yany Lopez, Ony Martinez, Sharon Quinsaat, and JM Wong.

Last, and certainly not the least, I extend my heartfelt gratitude to Darin Rogers for his patience and understanding. He was with me at the start of my work. Throughout the years, he wore multiple hats as my photographer, personal assistant and copyeditor. I owe him a great deal.

Chapter 1

Introduction

Placing Dreams and Building Homes

As I push my luggage cart along the hallways of Manilas Ninoy Aquino International Airport, I am greeted by a promise written on a huge life-size advertisement: Whatever your dream, we can build it. We build the Filipino dream (see Figure 1.1). This promise, exuding hope and trust, greets throngs of returning Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) and transnational Overseas Filipinos (OFs). But what is more interesting is that this comes from one of the Philippines largest real estate development corporations, Filinvest Land Incorporated. Filinvest is owned by one of the richest Filipino-Chinese families in the Philippines, whose wealth has been built on property development and banking (Rivera, 2003). Throughout the airport, other advertisements by large realty developers compete with Filinvest for much-needed attention from balikbayans (OF and OFW returnees). Ayala Land of the Ayala family, the largest and oldest real estate corporation in the Philippines, welcomes returnees with a confident sense of optimism with the tagline: The best homecoming. Homecoming to the best. Meanwhile, Vistaland, a development corporation of former senator Manuel Villar, prides itself for being the Philippines largest homebuilder and for building the country.

One of Filinvests We build the Filipino dream property advertisements in the airport.

Source: Arnisson Andre Ortega.

Outside the airport, similar property advertisements are scattered along the major thoroughfares of the metropolis. In shopping malls, numerous property booths are manned by real estate agents aggressively distributing promotional flyers to prospective buyers. Almost every quarter of the year, property fairs, such as the Philippine Real Estate Festival (PREF), bring together developers, realty brokerages and state agencies to promote their latest projects and symbolically proclaim a bullish real estate market.

Aggressive efforts to sell Philippine properties have extended beyond the state territory. In Seattle I attended the Pagdiriwang Festival, an annual Philippine Independence Day celebration organized by the citys Filipino community. Inside the exhibition hall, a Filinvest-sponsored booth displayed property flyers and brochures containing the same We build the Filipino dream slogan. The booth was manned by a Filipina broker who was answering inquiries from prospective buyers, mostly Filipino-American retirees and mixed race couples. In cities and territories all over the world with a sizeable Filipino community, tourism fairs, community events, and roadshows feature the latest property developments by high-end real estate firms.

I recount these instances to demonstrate the material manifestation of the current real estate boom, effectively saturating the everyday terrains of Filipino life within and beyond the Philippines. For years, the real estate industry has been hailed by both the Philippine government and business sector as the saving grace of the national economy for remaining resilient despite the global financial crisis of 2008. Los Angelesbased property services company CB Richard Ellis proclaimed the Philippines as Southeast Asias hottest real estate hub (PREF, 2010). For its 2014 real estate market survey, Urban Land Institute ranked Manila as one of the top real estate markets in the region, coming in as the fourth most investment-competitive city in East Asia and the regions best bet in residential property investments, beating other cities such as Seoul, Singapore, Osaka, and Sydney (Urban Land Institute, 2013). According to industry pundits, the current property boom is primarily fueled by end-user demand for housing from transnational OFs and returning OFWs and, more recently, by the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry (Colliers, 2014, 2013; Dumlao, 2008; Francisco, 2008; Magno, 2008; Lucas, 2007; Salazar, 2007).

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.