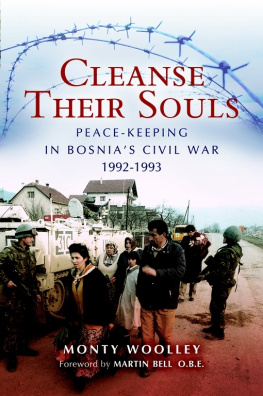

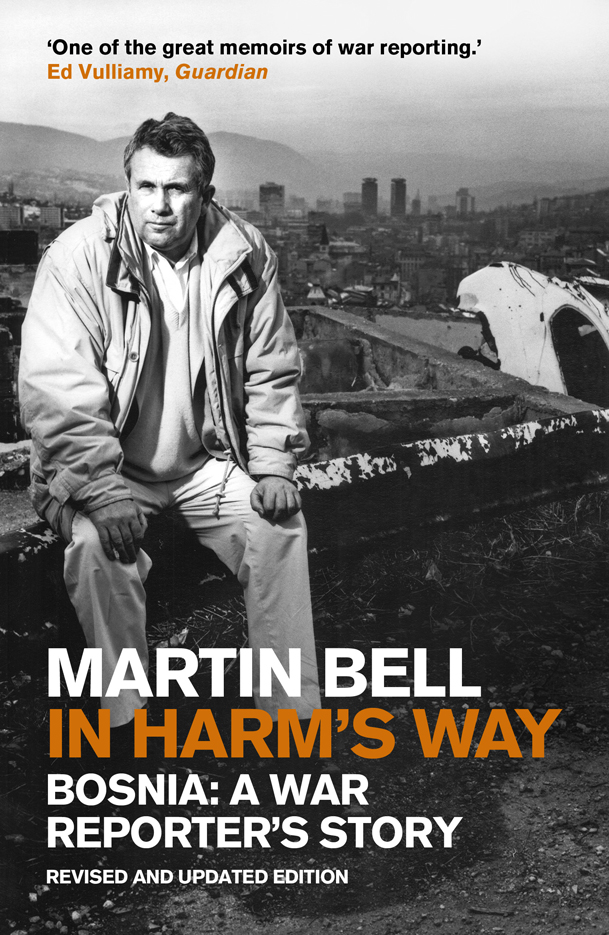

Compelling This acid, self-effacing and tautly written book is a journalistic jewel. The notes I made as I read it confirm gems of either description or analysis on almost every page His caustic appraisal of the mediums limitations must be read by all in our business accurate, balanced and self-critical It has humbled us all in the news business. I consider Martin Bell one of the greats

In its portrayal of the ordeal of Bosnia, and especially Sarajevo, this is a powerful book. It is also one which has much to say about the process of television news-gathering

[Bells] story is that of a civilized and passionate man cast into situations fraught with danger and livid with mankinds bestialities His sanity, clarity of vision and humanity are rare, especially coming from the savage world he inhabits and records for others

About the author

Martin Bell started as a trainee news assistant in the BBC Norwich newsroom in 1962. He joined the staff of BBC TV news in 1965, and his first foreign assignment (covering the overthrow of President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana) was in 1966. Since then he has worked on assignments in more than a hundred countries, including eighteen wars. From 1978 to 1989 he was the BBC Washington correspondent.

Martin Bell was awarded an OBE in 1992. He was also voted Royal Television Society Reporter of the Year in 1977 for his reports from Angola, and again in 1993 for his work in Bosnia.

On leaving the BBC he entered politics and was Independent MP for Tatton from 1997 to 2001. Since 2001 he has been a Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF.

He has written six books of which this was the first.

Printed edition published in the UK in 2012 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.co.uk

Previously published 1995, 1996 by the Penguin Group

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2012 by Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-84831-389-7 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-390-3 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN 978-184831-388-0)

sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street,

London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Printed edition distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Printed edition published in Australia in 2012

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Printed edition distributed in Canada by

Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright 2012 Martin Bell

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

For Melissa and Catherine

Contents

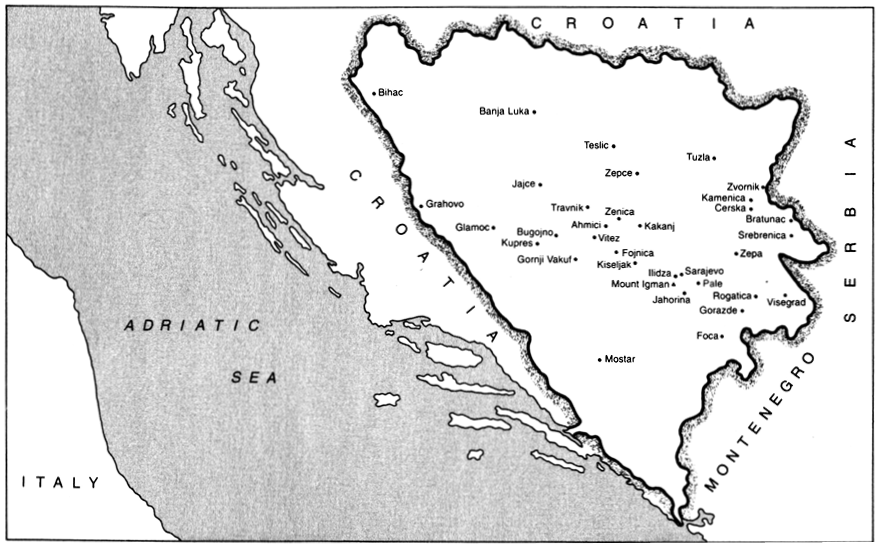

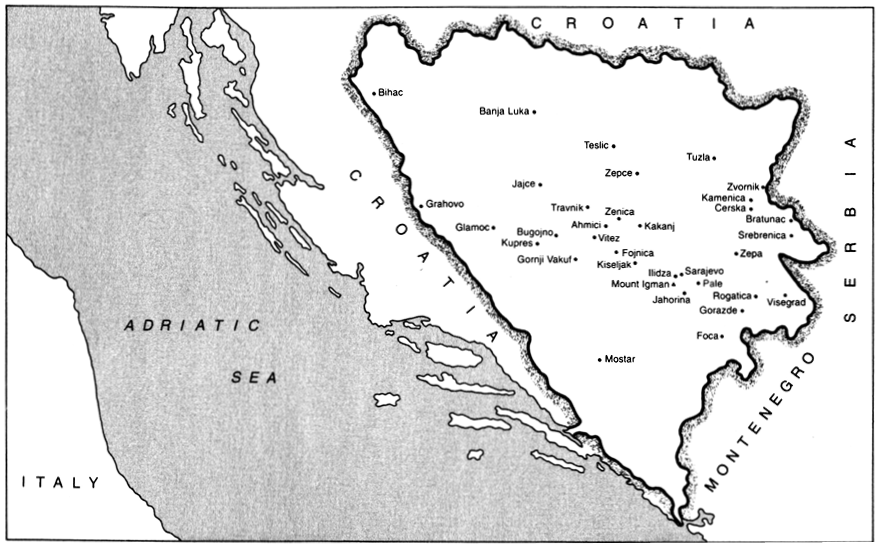

Map of Bosnia Herzegovina

Introduction to the 2012 edition

In Retrospect

Events pass from news into history and memories fade. In the blur of headlines and the frenzy of rolling news we regularly attach significance to things that are trivial and transitory and of no real importance at all, here today and completely forgotten tomorrow. This is especially so in an age when in politics and journalism we skim surfaces and confuse celebrities with heroes. Yet there are other events which cast long shadows and which we know, even at the time, will have a lasting impact. The war in Bosnia, which began in April 1992 and ended in December 1995, belonged in that second and more enduring category. After it was over, I chose as the location of my farewell report the Lion Cemetery in Sarajevo, a public park where the Bosnians had buried their dead because the citys main cemetery was in no mans land. Then and there, with the roll call of the victims as my witnesses, I called it the most consequential war of our time. And so it turned out to be.

This is a book about war and news and truth and the fault lines between them. The first edition was published two months before the Dayton agreement which silenced the guns. I wrote it entirely in the course of the war, concluding it by candlelight in my room in the Holiday Inn in Sarajevo: It is night-time in a war without end, and the supposedly fearless war reporter is flinching from the snipers bullets as they whip past his window. The rattle of gunfire and glare of the parachute flares over the Jewish Cemetery seemed to give the project an added urgency. What I was attempting, not by design but by necessity, was not just a conventional account of the progress of a war what we in TV news like to call the bang-bang but an explanation, driven by the circumstances, of how and why this appalling conflict began, whether it could have been avoided and why it was not stopped earlier. I was first of all trying to explain it to myself. We sleep-walked into it. How could it ever have happened? Did we really think that it was none of our business and that if we closed our eyes we could wish it away? Had we so little history that we had forgotten in which city Europes Great War began in 1914? Were ancient hatreds a sufficient alibi for hand-wringing, shoulder-shrugging and passing by on the other side? It seemed to me then, and I believe even more strongly now, that the blame did not lie exclusively with those who were doing and directing the fighting on the ground. It was spread more widely. And there are lessons still to be learned from it twenty years later.

Having been there at the time, and seen the documents provided to me by a diplomat of insight and experience, I am more than ever convinced that the charge I made in Chapter 3, of Western complicity in the war in Bosnia, was not only true and justified but understated. It was not thought through but had to do with unintended consequences. I could hardly believe that anything so cynical could have been contemplated, but sadly I had no need to be tentative. The truth itself is sometimes hard to believe.

The British in particular had a compelling case to answer. They reached an understanding with the Germans, for reasons of domestic political expediency on both sides, which lit the fuse for the war in Bosnia.

Early in December 1991 Prime Minister John Major paid a private visit to Chancellor Kohl in Bonn. With a general election imminent, he was seeking German agreement to the vital British opt-out clauses in the Maastricht Treaty. Based in Germany at the time, I waited in vain outside the Chancellors bungalow that night to discover what went on. The delegation came and went and I was none the wiser. But the Prime Minister was able, on his return, to subdue the clamorous Euro-sceptics in his party (then as now) by delivering victory on the politically toxic issue of the Maastricht Treaty. Was it Game, set and match? asked a helpful hack. The Prime Ministers spokesman gratefully agreed. Our Parliament still resounds to similar arguments.