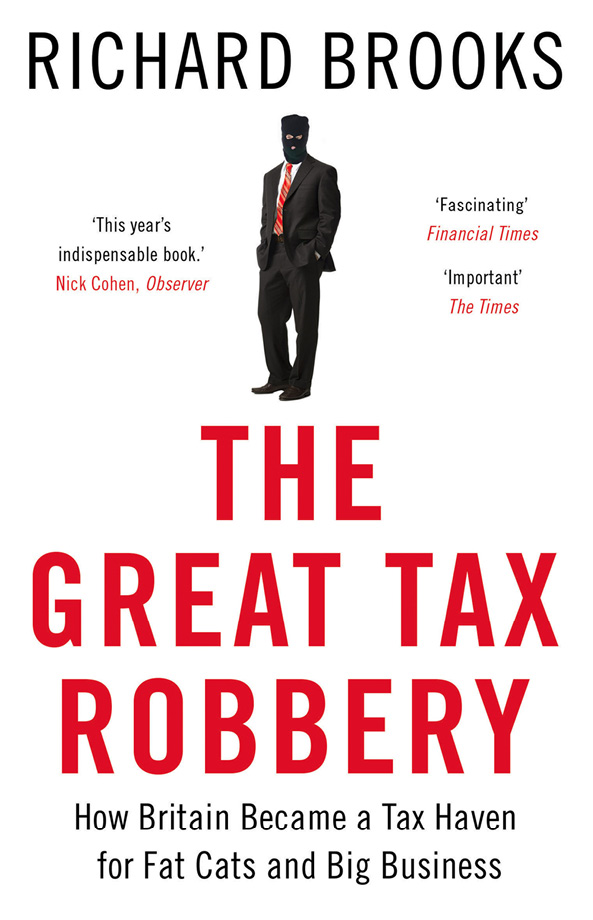

Former tax-inspector Richard Brooks reports for Private Eye on a range of subjects and has contributed to the Guardian , the BBC, and many other media outlets. With David Craig he was was co-author of the bestselling Plundering the Public Sector . In 2008 he was awarded the Paul Foot Award for Investigative Journalism. He lives in Reading.

The moral right of Richard Brooks to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

List of Illustrations

: UK corporate profits and corporation tax (1991-2011)

: The proportion of UK corporation tax paid by small companies

: Economic growth rates and average tax rates in the UK (1960-2000)

: No correlation: the economic growth rates of 22 OECD countries and their overall taxation levels

: Barclays buys a gas pipeline (and some tax breaks)

: Vodafone Group plc uses Luxembourg and Switzerland to loan Mannesmann AG 42.5bn and avoid billions in UK tax

: Behind closed doors: the locked office that is home to Vodafones Luxembourg companies multi-billion pound Swiss finance branches (Credit: Richard Brooks)

: Pearson US earns a tax break

: The business service centre hosting Pearsons Luxembourg companies and branches (Credit: Richard Brooks)

: Johnnie Walker goes Dutch

: A typical structure used by a London-based hedge fund to minimize tax

: Dodgers charter: Exchequer Secretary David Gauke (seated centre) and HMRC permanent secretary Dave Hartnett (seated right) sign the agreement with Switzerland that effectively de-criminalises tax evasion (Credit: HMRC)

Prologue

Committee Room 15, House of Commons,

12 October 2011, 3.21 p.m.

Public Accounts Committee chairman, Margaret Hodge MP, looked the countrys most senior tax inspector in the eye. I am going to start with a rather tough question. It seems to me that you lied when you told the Treasury Select Committee on 12 September that I do not deal with Goldmans tax affairs.

Dave Hartnett struggled to reconcile his statement to an earlier committee of MPs with the leaking that morning of an internal memo revealing that he had shaken hands with Goldman Sachs on a deal over a tax avoidance scheme. The normally assured civil servant shifted uneasily in his seat and claimed his response had been taken out of context. In any case, he had met the bank not to settle the tax dispute personally but to resolve a difficult relationship issue.

Goldmans scheme a plan to avoid millions of pounds in national insurance contributions on bankers bonuses via offshore companies and trusts had crumbled under legal scrutiny and other companies deploying it had long since coughed up. The famously belligerent US investment bank, by contrast, resisted for five more years, recorded the leaked memo. Yet when its resistance was eventually defeated by a tax tribunal and it came to agreeing the bill, Goldman was excused an interest charge of around 20m that was almost as much as the national insurance they had tried to avoid. Even the top taxman confessed this was a mistake.

The giveaway might indeed have been excused as a slip-up had it not slotted into a pattern of big business winning tax deals that would never be given to anybody else. While taxpayers out in the recession-hit real world were feeling the heat of increasingly impatient tax demands, the MPs were also grappling with another, far larger, sweetheart deal for a large corporation.

Just a few weeks before the Goldman Sachs settlement, the same taxman, Dave Hartnett, had sat down with the finance director of Vodafone and reached an agreement over an offshore scheme through which Britains third biggest company finances its worldwide businesses. The arrangement had saved the company several billions of pounds in tax over a decade but potentially fell foul of British anti-tax avoidance laws. Vodafone itself had set aside over 3bn to cover the tax and interest costs for just half these years but after meeting Mr Hartnett walked away with a 1.25bn bill for the whole lot, plus a raft of other concessions. Flush with his negotiating success, Vodafones finance director told stock market analysts the following day that his deal with the taxman was very good and preserves the very significant benefits of our efficient group tax structure, which we have benefited from for many years.

The deal was far from good for every other taxpayer in the country. Within weeks of it being exposed it had sparked a protest movement and enquiries from two parliamentary committees. Their questions were stonewalled by ministers and mandarins who repeatedly claimed that confidentiality laws barred any discussion. In fact, the MPs established, HM Revenue and Customs could choose whether to divulge details of its settlements to parliament. But the discretion was vested in Mr Hartnett, who, it so happened, had also approved the deals that he had negotiated and was now being asked to account for. My problem with this, thundered Hodge, is that you are the guy who does the deals, you are the guy who sits on the board that vets the deals, you are the Commissioner who vets the deals and you are the guy who decides what comes into the public domain, adding (for anybody left in doubt): It is an outrageous, unprecedented situation.